Another anemic election turnout. Why most people don’t vote, and what to do about it

- Share via

The sprawling city of Los Angeles, with its 4 million people and 500 square miles, shrinks at election time.

Especially primary election time.

In 2017, Mayor Eric Garcetti won a second term outright with 81.4% of the returns, but 8 out of 10 voters blew off the election.

Votes in Tuesday’s primary are still being counted, but to no one’s surprise, the vast majority of voters sat out the election for L.A. mayor, council seats and various county, state and congressional races. Statewide, the numbers were about the same based on early indications. Not historically low, but nothing to cheer about.

So why does this keep happening, even as it becomes easier to vote than to order a pizza, and even as festering issues such as homelessness drive demand for fixes?

“Unfortunately, I did not participate,” a young man named Jeremy told me as his shift ended at a COVID-19 testing site at the Eagle Rock Rec Center.

At least he knew who ran for mayor, which can’t be said of all the people I interviewed in the days leading up to the election.

“I would have voted for Karen Bass,” said Jeremy, and he told me he probably will in the general election. “But I had a lot of obligations and some personal things going on.”

On the other side of the rec center, 31-year-old Andy Perez, a breakdance instructor, told me he hadn’t voted in years and doesn’t intend to change.

“Honestly, it gets in the way of my daily activities,” Perez complained, saying that his mother works at home as an appointment scheduler and kept getting interrupted by political robocalls.

Those calls are irritating, I agree, but that answer just isn’t working for me. Perez offered another explanation that was slightly better. He said that the last time he voted, his candidates “didn’t do what they had promised, from what I heard.”

As I said in a column last week, when I chided the no-shows, you can’t dismiss the reality of outright laziness as a factor. But there’s more to it.

Empty promises and failed policy have convinced many that a vote doesn’t matter.

“We have not seen the results we’ve been expecting,” said Kevin Wharton Price, of Leimert Park.

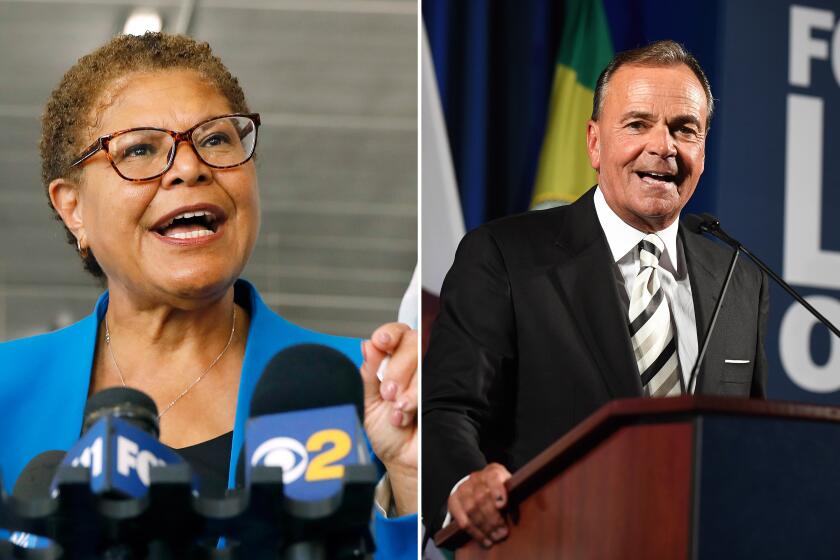

He had told me before the election that he was weighing his options, but wasn’t convinced that top mayoral candidates Rick Caruso or Karen Bass had an agenda that would improve things for struggling people of color.

When I called Price after election day, he said he didn’t vote. But he will in November’s general election, he said, if one of the candidates can convince him — and his community group, Africa Town Coalition — they’re not just serving up a bunch of campaign rhetoric.

“They have to come forward with serious policies and show what they’re going to do on a grass-roots level,” Price said. He’s looking for something definitive and convincing on a strategy to address homelessness “without being abrasive or overbearing,” he added.

Mindy Romero, founder of USC’s Center for Inclusive Democracy, said primary elections — particularly in presidential midterm years — have had low turnouts for decades, partly because they’re like warmups for the runoffs. But highest participation is often among older, whiter and sometimes more conservative voters, so general election ballots skew demographic realities.

“Overwhelmingly, stories about voter turnout are basically blaming the voter in one way or another for apathy,” said Romero, but when she studies why people skip elections, some of the reasons are as rational as the explanations for why people do vote.

When I told her about Price, the Leimert Park resident, she said that doesn’t sound like apathy. He obviously cares about his community, she said. But he thinks he’s getting lip service from candidates. And politicians, of course, oversee bureaucracies that are inefficient and unresponsive, further eroding faith in government.

“It’s a political system that’s not working for the people, and some people vote anyway despite that,” said Romero. “But even they struggle with feeling like it doesn’t make a difference.”

It doesn’t help in California or elsewhere that newspapers and reporting jobs have disappeared, leaving politicians less accountable and the public less informed. And a long ballot, like the one this month, requires a research investment that some working people don’t prioritize. Even a regular voter like me is overwhelmed by long lists of candidates for judgeships.

So what can we do about all of this?

Well, if politicians delivered on promises, that’d be a good start in the fight against cynicism.

Romero said we need an infusion of civics lessons, by schools, candidates and social organizations, to make it more obvious why engagement is a foundation of a democracy.

Why not essay contests in high schools and community colleges on the benefits of voting, with scholarships for the winners?

Caruso seems to have a few bucks at his disposal and loves running TV and social media ads. So why not a public service announcement blitz on the long and sometimes bloody history of the fight for voting rights in the United States and around the world?

Dwayne Gathers, a government and business affairs strategist in Hancock Park, was so dismayed by low turnout in recent years, he began a podcast at civitasla.com to chat about local affairs with a diverse array of regular people and some public officials.

“People need to see others like themselves who are participating in creating, building and serving community,” Gathers said. “And as that participation begins and grows, one manifestation is understanding the importance of voting.”

Romero said another way to pump engagement is to talk to those who do vote rather than talk about those who don’t.

At the Eagle Rock Rec Center, Dan Hawkins was getting ready to umpire a baseball game and told me he voted for Caruso because he wants something done about homelessness.

“If we don’t vote,” Hawkins said, “what happens to society?”

When Jeremy told me he was too busy to vote but favors Bass, I asked why. He pointed to his colleague, 24-year-old Rodolfo Oliveros, and I chased after him before he drove away. Oliveros told me his politics align more closely with those of Bass, and he is suspicious of Caruso’s switch from longtime Republican to Democrat.

The next five months of campaigning will likely amplify the partisan schism between Rick Caruso and Karen Bass.

Oliveros said he got into politics while at UC Davis, where he was a Transformative Justice in Education fellow. In addition to working in COVID testing, he said, he founded a San Fernando Valley nonprofit called A Better Tomorrow, and told me that to draw attention to the election, “I’m on Instagram, always posting and blowing it up.”

Oliveros said he understands the cynicism, but “I think there has to be faith in it. ... If you vote, there’s the possibility of some momentum building to get the right people in and the wrong people out.”

Maybe one of L.A.’s hundreds of philanthropists could sponsor a civics initiative and hire the likes of Oliveros to spread the word. And if that happens, I’d like to nominate another young ambassador to the cause.

Many years ago I met a Fairfax High student named Miriham Antonio, who lived in a Koreatown apartment shared by two families. Hers included two brothers and a mother who worked a night shift as a janitor. I rode the bus to school one day with Antonio, who dreamed of attending a good college and going on to law school, and at Fairfax, she ran a voter registration drive.

Antonio, now 25, just graduated from USC and has been accepted to the UC Irvine law school. She’s a little worried about paying the bills, and is doing janitorial work with her mother after having worked in recent years for a school board member, a gubernatorial candidate and a city councilman.

Just like Oliveros, Antonio said she understands why so many young people are cynical or disaffected. But yes, she said, of course she voted.

“I mean, my whole thing is that it’s going to come down to keeping people accountable,” she said. “I think that until people realize we have to hold politicians and bureaucracies accountable, nothing’s going to change.”

Steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.