‘Okie’ was a California slur for white people. Why it still packs such an ugly punch

- Share via

They flooded into California fleeing poverty in their homeland. The public denigrated them as dirty and crime-prone — a threat to the good life.

Authorities harassed the newcomers out of city limits, forcing thousands of families to crowd in enclaves and take low-paying jobs. And when even that couldn’t drive them away, law enforcement set up blockades on the California border.

This was the story of the Joads, the family at the center of John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath.” I read it as a senior at Anaheim High School, and it remains my favorite novel all these decades later. Its biblical allusions, sparse-but-beautiful prose, critique of uncaring capitalism and praise of a proactive government makes it a multitiered masterpiece.

But what speaks to me more than anything about “The Grapes of Wrath” is how the saga of the Joads so closely mirrors that of my family.

The resilience of Ma Joad, the idealism of Tom, the tragedy of Pa, the personal growth of Rose of Sharon — they were my Mexican-born parents, my aunts and uncles, my native-born cousins, my siblings. The book has colored my idea of California ever since. Though it was fictional, Steinbeck based it on the real-life exodus of Dust Bowl refugees, especially those from Oklahoma. California can be cruel to desperate people — yet only in California could the persecuted transform their hard times into dreams they would’ve never found back home.

I especially connect to a slur that the Joads and their real-life contemporaries had to endure: “Okies.”

There is a scene in “The Grapes of Wrath,” toward the end, when Pa Joad had just about reached the point of despair.

Californians turned the term — long used as shorthand for an Oklahoma native — into an insult. My family members and other immigrants from south of the border had similar insults thrown at them, including “Mexican” and “paisa,” or hillbilly.

But both groups took the invectives back from the haters and transformed them into markers of cultural pride. Country music legend Merle Haggard famously recorded “Okie from Muskogee” to push back at city folks who thought his kind backwards, while another country icon, Vince Gill, titled his 2019 album “Okies.”

In an opinion piece for this paper, Gill talked about how the album title connected him to other maligned people.

“I appreciated that Okies aren’t that different from other groups who were scorned and stereotyped,” Gill wrote. “They were hardworking people who were willing to do whatever it took to survive during one of our country’s most challenging times.”

It was in that spirit of respect that I used “Okie” in an Aug. 5 obituary for Salvador Avila, the co-founder of the Avila’s El Ranchito Mexican restaurant chain. He opened his first spot in Huntington Park in the 1960s, at a time when the city was “still an Okie” center instead of one of the most Latino cities in the United States, I wrote.

I thought nothing of that line, because it was true. Southeast L.A. County is where many Dust Bowlers settled and where they and their descendants held political power for decades. To merely say “white people” would have downplayed the history, because the Okie experience in Los Angeles was distinct from other white Americans in the region like, say, Midwesterners or Southerners.

Almost as soon as I published my piece, the critiques came in.

Teri O’Rourke of Palm Desert, whose grandparents left Oklahoma in the 1930s, said my use of “Okie” brought back memories of “the people in the ‘50s and ‘60s who thought Okies were stupid and lazy.”

Karen Hamstrom claimed “Okie” was “extremely offensive language” that was beneath me.

“While the Depression-era generation that endured those taunts may be mostly gone, those words are still used with scorn and derision to imply filth, stupidity, and a shallow gene pool,” she wrote. “Given how quickly you take offense to words and actions you deem discriminatory to your culture, I expect better from you.”

Danny Esparza viewed “Okie” as a “bitter descriptive” and claimed Huntington Park in its white heyday “was a beautiful [thriving] city with a financially thriving downtown area. People came from all around to shop there. To use your racist vehemence, it is now a Mex trash pit.”

Nothing like self-hating Latinos to brighten your day.

The backlash I received over “Okie” surprised me. I thought its sting was a matter of history. The group long ago assimilated into “white” society in Southern California and moved into the middle class. The New York Times used “Okie” as a crossword puzzle answer (to the clue “Resident of the 46th state”) just last week.

On the other hand, the term has slowly disappeared from this newspaper. Blake Hennon, a Times copy desk manager, told me that the dictionary used by our copy editors describes it as “often a disparaging term.”

Hennon said he “would advise against calling anyone an Okie. But it’s not wrong to note that people have been called that in historical context.”

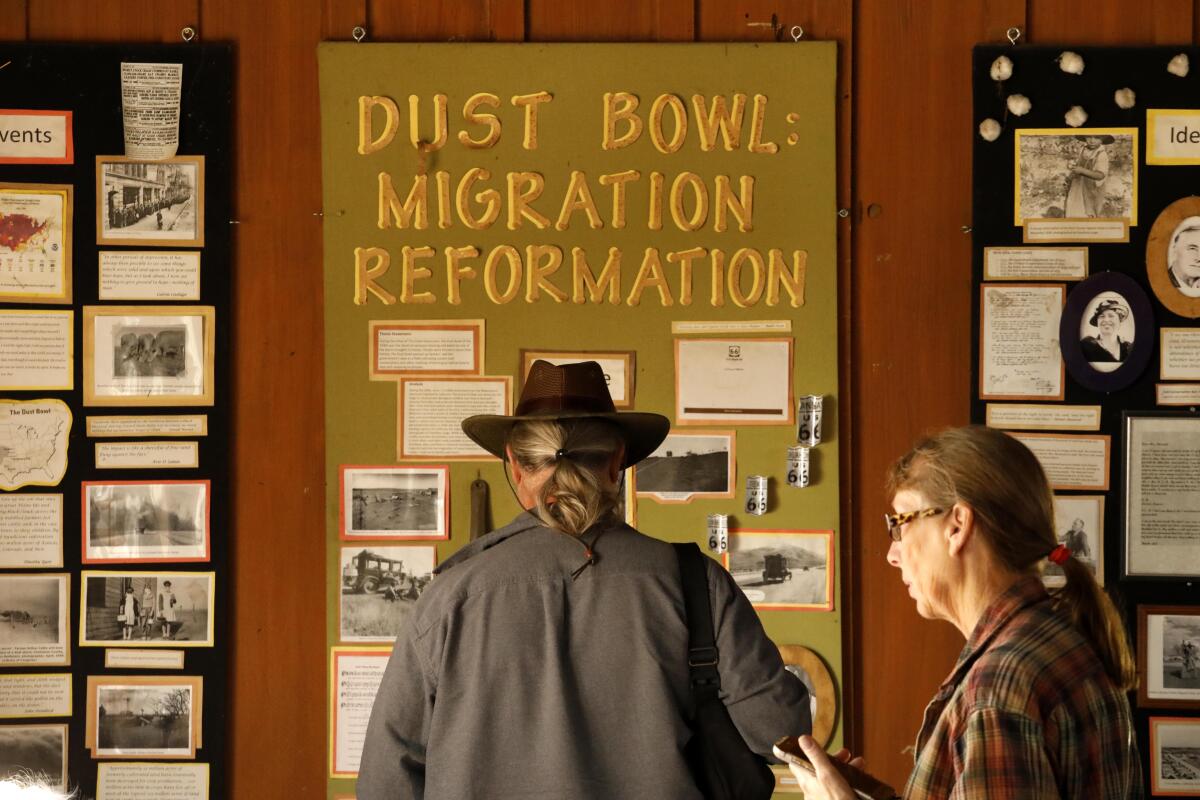

The Dust Bowl Festival at the historic Weedpatch Camp, immortalized by John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath,” ended this year after three decades. The Okie generation is fading in California, but migrant stories will never end.

Otto Santa Ana, a professor emeritus of Chicana and Chicano studies at UCLA who specializes in the linguistics of ethnicity, said my dustup was a classic case of language evolution.

“One generation could think of it in a bad sense, the way ‘Chicano’ was a negative term for my mom, and it became a positive term for me,” said Santa Ana. “We create a speech community among our peers, and not across generations. So that generation that felt the slur will still feel it.”

After talking to the profe, I called up some Oklahoma natives: two of my millennial L.A. Times colleagues.

Assistant editor Jaclyn Cosgrove hails from Arpelar, a town with just under 300 people. At a high school government convention in Las Vegas in the early 2000s, they recalled, their delegation reworked J-Kwon’s song “Tipsy” so that the lyrics proclaimed, “Everybody here wants to be an Okie.”

“I remember some of the older folks in my life mentioning that it was a pejorative term, but that just seems less so,” Cosgrove said. “For me, you’re talking about a people who didn’t want to give up, and kept trying and trying to chase the American Dream and find a safe place for their families to live. Maybe being an Okie for some people is insulting. I just can’t see how it’s a bad thing.”

Metro reporter Hailey Branson-Potts is from Perry (population 4,500) and just came back from her hometown bearing Okie Kid Blend coffee for her husband, Enid native and Times video journalist Mark Potts.

“By the time I was growing up, it was something to be proud of,” said Branson-Potts.

Only after she and her husband joined the Times in 2011 and began to reading up on California history did they realize the negative connotations “Okie” once had here.

“It was shocking to me,” she said. “It’s hard to wrap my head around, because ‘Okie’ is such a badge of pride back in Oklahoma.”

Branson-Potts does a lot of reporting in rural California. White residents in the north say they’re from “Calabama,” while those in Kern County regularly use “Okie,” as evidenced by the billboards advertising “Okie Fry Pies” that I saw on the outskirts of Bakersfield this spring. She said my critics must be far removed from modern-day Oklahoma to be angered by seeing “Okie” in print.

“When you grow up poor or adjacent to poor, you look for pride in the things you do have, whether it’s history or your family or even what people call you,” she said. “My guess is that at this point in time, people offended by ‘Okie’ are people who didn’t have to worry about money.”

But the paradigm has recently flipped in deep-red Oklahoma.

There, she said, “‘California’ is a four-letter word.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.