Building a bridge between Spanish and English worlds is new L.A. Times columnist’s mission

- Share via

I have always known the United States in one way or another. I was born in Mexicali, Baja California, and since I was a child I have seen the border region transform in stride with the political times. I saw the last vestiges of the Bracero Program, which brought in Mexican workers initially to replace the labor shortage during World War II.

I also distantly remember the marches in which the parents of several of my friends who worked in the Coachella farm fields took part, and who joined the strikes and boycotts led by César Chávez when he was organizing the United Farm Workers.

While the border continued to transform, I went to study journalism at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. There, I dedicated the first six years of my professional life to the analysis of the unionization movements in Mexico. Then I decided to immigrate to the United States.

I have lived here for about 35 years. In my career as a journalist I have been based in San Diego, Santa Ana, Long Beach, San Jose, New York and New Jersey, and for the last 10 in Los Angeles. I have worked at small newspapers without resources and at large publications such as the magazine People en Español, the Orange County Register, San José Mercury News and the Los Angeles Times.

After directing newspapers for more than 20 years, I have the enormous pleasure of being able to dedicate more time to writing and telling the stories of our community, those that rarely reach the big publications and that relate the daily lives of people who without much fanfare are true role models in their communities.

As I have traveled across the United States, I have been simply one more immigrant, with the same needs and fears as others, but also with the same desire to get ahead. I remember my first job in the United States in Escondido, in an avocado packing house. I had to stow boxes for eight long hours, and whenever I complained, the packers, who worked piecemeal, encouraged me and ask me: “You’re tired, güerito?” They were dying of laughter, but they didn’t stop for a second.

There were 10 women from Oaxaca, Michoacán and Jalisco. Single mothers with great needs. Among them they organized cundinas — a savings group — and sold tacos, aguas frescas and trinkets. They took care of the children in shifts, because they could not pay for child care, and they lent money to each other to pay the rent. Despite all their needs, they split a taco for me to share with them.

I also got to know life around swap meets, where farm workers, construction workers, gardeners, nannies, domestic workers and laborers meet to have a social life beyond their jobs. Some had fallen in love there, or divorced. There they listened to the latest music from their favorite artists, and there they bought wedding dresses, flowers for a quinceañera, and little baptism outfits.

Those swap meets were the center of social life in a world that seemed hidden from the rest of society, but grew in full view of all. There, many immigrants found their true vocation as merchants or businessmen. There, entire families survived economic difficulties when they discovered that they could even sell stones if they wanted to.

On this tour I saw how President Reagan’s 1986 amnesty changed the lives hundreds of thousands of immigrants living in the United States who didn’t want to lose the connection with their families and homeland cultures. The resulting wave of family reunification altered the dynamics of many communities. Cities like Vista or San Marcos, in north San Diego County, experienced unprecedented growth in 10 years. The surnames López, Pérez, Martínez and Gutiérrez began to abound in schools, and school districts had to create bilingual programs for their new students.

With sadness I observed the loss of the Spanish language by second-generation children. And I have also had the pleasure of seeing some of them recover the language of their ancestors when they began to realize that not speaking Spanish was also the loss of their identity.

And as I witnessed the loving solidarity of the women of Escondido, I also saw the exploitation of Latinos by other Latinos in the farmworker camps, like at the former Rancho de Los Diablos, also in north San Diego County, where those who had papers to work legally “rented” their papers in exchange for 30% of the salary of those who did not have documents.

In that same camp I saw the entrepreneurial spirit of some, like the impeccable young man who at that time drove a late-model red pickup truck and lived in a small house made of cardboard and tin on the side of a smelly stream.

I remember asking him, intrigued, “What do you do for a living?”

“He sells beer,” one of his customers told me.

I mentally counted. At that time, around 1,200 people lived Los Diablos. If he sold 600 beers a day, at $1 apiece, he could make about $18,000 a month. On weekends the sale was at least three beers per capita. Not bad, and without paying taxes.

But he is an exception. In reality, undocumented workers, who work one, two and even three jobs, pay taxes like the most American of citizens. But they are not entitled to benefits of any kind.

I was also able to see the arrival of Gov. Pete Wilson and the tension generated by his infamous Proposition 187 — which, by the way was approved by California voters, and whose objective was to make life miserable for undocumented immigrants.

As never before, I saw the state of California, divided and spiteful.

But I also saw my children, and the children of my friends, and the children of the neighbors, take to the streets to march against Proposition 187.

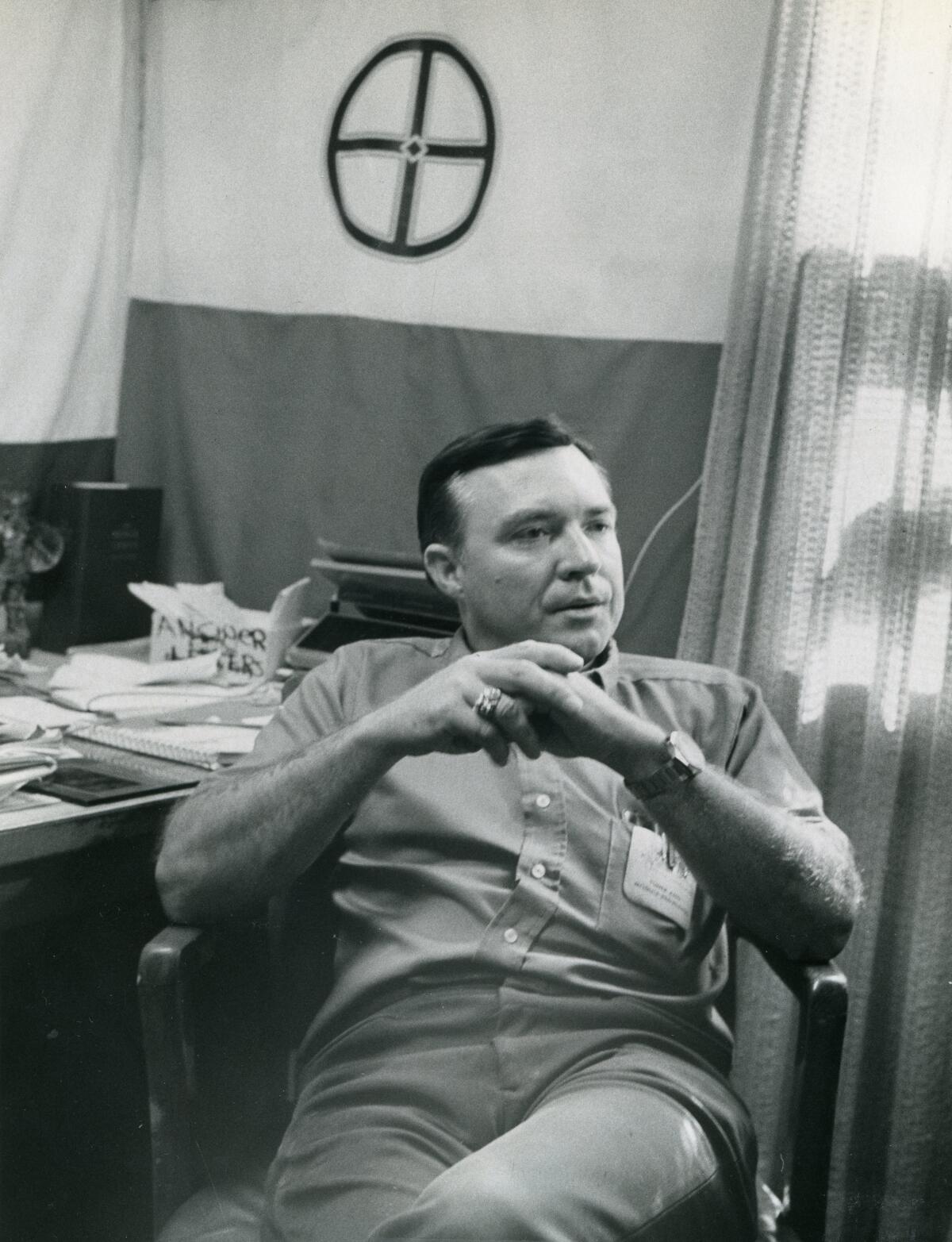

I saw them holding school walkouts and confronting the many racist groups that began to proliferate in the most unlikely places, like in Fallbrook, where I had the opportunity to interview Tom Metzger, leader of the White Aryan Resistance, who told me, “I sincerely love Mexicans, but I love them in Mexico.”

And then I saw these young people become activists and start holding political office in different parts of the state. Giving hope for a better state for all.

When job opportunities arose in New York and New Jersey I encountered a face of the Latino/Hispanic community that I hadn’t known before: the one from the East Coast. As Dominicans arrived in the Big Apple they mixed with the Boricuas and Cubans and the incipient Mexican community forming in historically Colombian neighborhoods. I also saw the arrival of wealthy Latinos from all over Latin America who made Miami one of the main Latin American capitals.

I got to know the Dominican mofongo; the Cuban ropa vieja, the Puerto Rican coquito, and I listened to the plenas, the son, the salsa, the merengue and the bachata, and I understood that although we have many things in common, we Latin Americans and Latinas/os have many different customs, traditions, flavors, accents and languages. Do we often “forget” (or is it better to say ignore?) these other Latinos whose main language is Mayan, Nahuatl, Purepecha, Mixtec, Quechua or Guarani?

And that’s where this column comes in. My objective is to build a bridge to this entire world that lives in Spanish and that seems to not exist for the rest of society. And it’s not like some think, that “they should learn English to integrate into society.” Many of us do speak English, but prefer to communicate in Spanish, because this language is part of our identity.

I want to show our faces and share our stories. Through this column, I want to reveal the daily activities of these men, women and children who work, create and celebrate life in Spanish harmonized with English.

This bridge will grow from telling stories, like mine, like the neighbor’s, like the gardener’s or the cook’s. I guarantee you will be amazed at the richness of their lives.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.