Appeals court rules lawsuit by family of San Quentin guard who died of COVID-19 can proceed

- Share via

A federal appeals court on Monday rejected California’s bid to toss out a lawsuit filed by the family of a corrections officer who died three years ago from COVID-19 after state officials ordered the transfer of infected inmates into his prison from another facility.

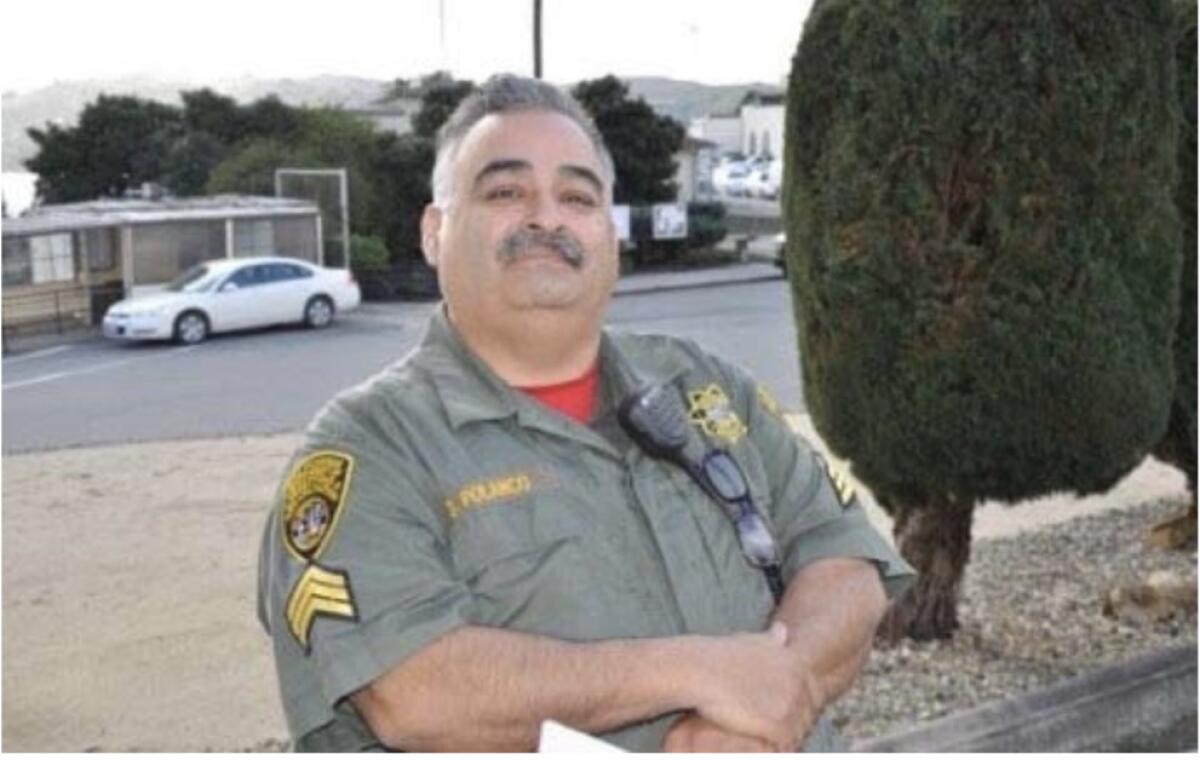

Sgt. Gilbert Polanco died in August 2020, less than three months after buses carrying more than 120 inmates from an outbreak-ridden prison in Chino arrived at the gates of San Quentin. According to court filings, the resulting spike in infections at the Bay Area facility killed at least 26 prisoners as well as the 55-year-old sergeant. His family sued in federal court the following year, accusing the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation of violating his constitutional right to due process by failing to protect him from a “state-created danger.”

In response, the state asked to dismiss the case and argued that its employees should be protected by qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that frequently shields government officials — such as police and prison guards — from liability in lawsuits.

On Monday, two judges on a three-judge panel at the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decided prison officials did not qualify for that protection because they knew how dangerous it was to transfer inmates from a prison battling an extensive outbreak into a facility without any known COVID-19 cases.

“Defendants — a group of high-level officials at San Quentin and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation — were aware of the risks that COVID-19 posed in a prison setting,” the judges wrote. “All had been briefed about the dangers of COVID-19, the highly transmissible nature of the virus, and the necessity of taking precautions to prevent its spread.”

Michael Haddad, one of the lawyers representing Polanco’s family, welcomed the court’s ruling.

“The state has been trying to escape responsibility, using these legal technicalities to avoid accountability,” he told The Times.

The state attorney general’s office, which is representing the prison system and prison officials in the case, referred a request for comment to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. The department declined to comment due to pending litigation, including a possible appeal.

Throughout the pandemic, crowded jails and prisons across the country were particularly deadly environments, especially for medically vulnerable inmates and staff. But some facilities — including San Quentin — came under particular fire for failing to prevent and contain outbreaks.

In early 2021, a scathing State Inspector General’s report found officials ignored the warnings of front-line health workers and pushed for the hasty transfers from Chino to San Quentin. Days later, the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health hit the state’s oldest penitentiary with a $421,880 fine, the largest single penalty in the state over workplace safety violations for failing to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The inspector general blamed state corrections officials for the outbreak at San Quentin prison, where 28 incarcerated persons and one staff member died of COVID.

In early 2020, Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order suspending the intake of new inmates into prisons across the state, and correctional health officials adopted a policy opposing the transfer of inmates between facilities.

By May of that year, some prisons — including San Quentin — still had no known cases of the virus. Others, such as the California Institution for Men in Chino, had been hit hard, with hundreds of documented infections. According to court filings, it was in an effort to protect vulnerable prisoners at Chino that officials decided to move more than 120 men with high-risk medical conditions to San Quentin.

“The transfer did not go well,” the judges wrote.

Many of the men “packed” onto the buses hadn’t been tested in several weeks. Some even showed symptoms of illness during the trip, but according to court filings officials did not quarantine them upon arrival. Instead, the new arrivals were all housed in an area with grated doors and ample air flow, and they were allowed to use the same showers and mess halls as other inmates already at the facility.

Two days later, Marin County public health officials learned of the transfers and recommended quarantining the new inmates to protect the men who were already there. But according to court filings, prison officials “did not heed” that suggestion and instead ordered that the county’s public health officer “be informed that he lacked the authority to mandate measures in a state-run prison.”

Within days, 25 of the transferred inmates tested positive for COVID-19. In a matter of weeks, the prison went from having no confirmed cases of the virus to having nearly 500.

That June, the court-appointed medical monitor overseeing California prison healthcare asked a group of experts to investigate the outbreak at San Quentin. The memo they authored afterward criticized the prison for failing to provide masks or do enough testing, and warned that the outbreak could escalate into a full-blown crisis.

By July, more than 1,300 prisoners and 184 staff at San Quentin had tested positive for the virus. That figure soon increased to more than 2,100 prisoners and 270 staff — including Polanco.

At the time of the transfer, the father of two had several high-risk health conditions that made him particularly vulnerable to dying from COVID-19. Yet, according to court filings, one of his duties was to drive sick prisoners to local hospitals. Previously, his widow told The Times that he often had to work double shifts because so many of his co-workers had quit — in part due to a shortage of masks inside the prison, she said.

That June, Polanco became sick. By July his condition worsened and he had to be hospitalized. He died of complications from COVID-19 in August.

“This is a textbook case of deliberate indifference,” the federal court wrote. “Defendants were repeatedly admonished by experts that their COVID-19 policies were inadequate, yet they chose to disregard those warnings.”

Prison officials previously said they were not indifferent because they ordered the transfers in the hope of protecting the high-risk prisoners at Chino. Plus, they said, guards “are free to refuse to work in a prison.” By not quitting his job, they argued, Polanco knew that he’d assumed some risk.

In Monday’s ruling, the federal court pointed out that the prisons still could have properly tested and screened the incoming prisoners, which “would have made the transfer safer for both San Quentin employees and the transferred inmates.”

Ten new judges in 3 years have turned the federal appeals court far more conservative than it has been in decades. And the full effect hasn’t hit yet, judges say.

One of the federal jurists on the three-person panel — Judge Ryan Nelson, an appointee of former President Trump — disagreed, laying out his reasons in an eight-page dissent.

“Hindsight is 20/20, and we cannot view the clearly established inquiry through the lens of what we know or believe to be true now,” Nelson wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented. Therefore, to say that the law was clearly established in my view disregards the exacting legal standard to overcome a qualified immunity defense.”

It’s not clear whether the state will continue pursuing appeals after Monday’s decision. If not, Haddad said, the case will return to the lower court as both sides begin the discovery process leading up to a possible trial.

The decision is an important step forward for the Polanco family’s legal process, Haddad said.

“But they’re so absolutely distraught about the loss of their husband and father, I don’t think it’s going to be much consolation for them,” he said. “They are hoping for justice.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.