A PhD and full class load gets a CSU lecturer $64,860 a year. They are striking for change

- Share via

Olga Garcia is devoted to the East Los Angeles community where she’s lived most of her life. A graduate of Garfield High School, she’s spent nearly half of her teaching career — nearly 11 years — in the college of ethnic studies at Cal State L.A.

But in the Cal State system, her role is considered temporary. Garcia is among the thousands of lecturers who make up a majority of the teaching force in the sprawling 23-campus system. As “contingent” faculty members, they work on contracts that can run as short in duration as a semester and are not eligible for tenure.

Garcia, who is currently on a three-year contract with the university, has taught a full load of five courses nearly every semester of her career in the system, scaling back to four classes at times for mental and physical health reasons.

“I am not a temporary employee, but the university putting me under that category allows them to give me less benefits, less pay,” she said.

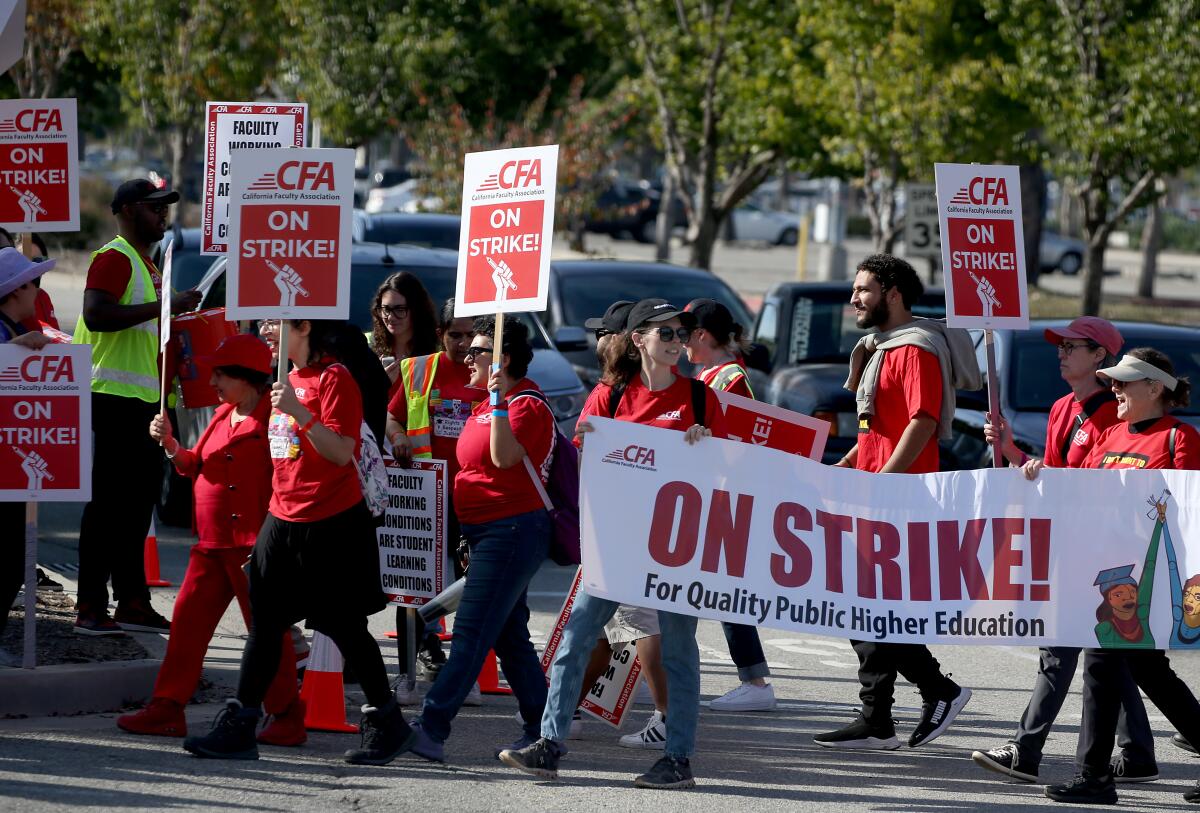

Support for lecturers and other contingent faculty — including counselors, librarians and coaches — was a driving force behind one-day strikes held by the California Faculty Assn. at four Cal State campuses earlier this month. They lamented the realities many lecturers face. Without predictable raises based on experience or the promise of consistent work, many faculty must teach at multiple campuses to survive or live in financial precarity.

The union has announced a weeklong, statewide strike to take place next month, but said the system could avoid a walkout by “presenting serious, fair, and reasonable proposals to address long-standing inequities.”

The faculty union and the Cal State system remain divided in contract negotiations. Faculty want a 12% raise for 2023-24, but the system says it is not possible.

During more-difficult months, Garica, who earns less than $65,000 a year as a lecturer in the Department of Chicana(o) and Latina(o) Studies, said she’s had to borrow money from colleagues to pay for food and gas to get through a pay period.

“It’s embarrassing,” she said. “I can’t save. I can’t plan.”

More than half of Cal State faculty members are lecturers, full or part-time workers assigned to temporary appointments. The tilt toward conditional labor troubles academics across the country: In fall 2021, 68% of faculty members in the nation’s colleges and universities held contingent appointments compared to 47% of faculty in fall 1987, according to research from the American Assn. of University Professors, a nonprofit membership organization.

Glenn Colby, a senior research officer with the association, said the proliferation of contingent faculty across the country is in part due to state funding that has not kept pace with increased student enrollment over the decades. Employing tenure-track professors costs more than contingent faculty.

In 2021, 14,400 instructional staff members in the Cal State system were part-time, the vast majority of them contingent workers, according to data compiled by Colby. That compares with 9,730 instructional staffers who were part-time in 2009-2010.

“There’s something going on in the Cal State system where the reliance on part-time faculty has skyrocketed since the Great Recession in 2009, at a much greater rate than nationally,” Colby said.

Among the full-time faculty, the research also found that women and certain racial groups, including Black and Latino members, held contingent appointments in greater proportions than men and white or Asian members.

A Cal State spokesperson said in a statement that hiring decisions are made on a campus-by-campus basis and are based on several factors, including department budgets and particular class needs.

“CSU lecturers and non-tenure-track counselors play an important role in providing instruction and critical services to our students,” said Hazel Kelly, the spokesperson. “They are afforded hiring priority over new hires and are eligible to receive three-year appointments.”

During the recent Cal State strike, thousands of faculty members walked off their jobs to demand higher raises and to voice discontent over how the system has handled recent contract negotiations.

Among the union’s top demands: Raise the salary floor for its lowest-paid full-time faculty members — many of whom are lecturers — from $54,360 to $64,360. The base salary for lecturers with doctorate and other terminal degrees is $64,860, which the union wants to raise to $69,860.

The union is also asking for a 12% across-the-board pay increase for the current academic year; CSU has offered a 5% raise in each of the next three years, with the last two years dependent on state funding.

Under the union’s proposal, Garcia’s base salary would get bumped to $69,860, along with the across-the-board increase. The extra money, she said, would give her more breathing room.

“What we’re asking for is just an acknowledgment of our work. It’s not going to change my life dramatically,” she said. “But it will make a difference.”

Faculty members and the Cal State officials are locked in what’s called reopener bargaining, which allows the sides to negotiate parts of an existing contract. Apart from pay, current negotiations don’t include proposals for expanded protections specific to lecturers and other workers classified as contingent.

But Meghan O’Donnell, an associate vice president for lecturers in the California Faculty Union, said lecturers across the system want to push for more work stability when the full contract is up for negotiation next year.

“We really want to create more permanency for lecturer faculty. Not necessarily equatable to tenure but something that gives people some sense of belonging to the university,” she said. “A sense of respect and dignity in their work.”

O’Donnell said the system has increasingly relied on lecturers to teach courses since the early 2000s, increasing their numbers during budget clampdowns during the Great Recession.

“The reality is, when you have a crummy working condition as a lecturer, that does have an impact on what support we’re able to provide to students,” she said.

Oftentimes lecturers face uncertainty about what course they will be teaching, according to the union. Lecturers don’t get paid for classes that are canceled for low enrollment — and that can happen after the semester starts.

Deborah Brown, a lecturer at Cal State L.A., said she was once set to teach an African American history class but was told she would instead have to teach a course on critical race theory. She had days before the class was scheduled to craft a syllabus and devise a curriculum, as emails from students began popping up in her inbox about the start of class.

“It’s not the ideal teaching situation, teaching students when you’ve had less than a week to prep for a class,” she said.

Brown said she earns less than $1,000 each month for the two classes she teaches, supplementing her income by teaching a full slate of five courses at Riverside City College.

She remains in the Cal State system because she’s drawn by the rigor of teaching upper-division courses and working in a community of Black scholars.

“What keeps me there is the connection to the work,” she said. “Because it’s definitely not the pay.”

The instability isn’t limited to lecturers: The system also employs counselors as contingent faculty, many who say they are overwhelmed with caseloads as they deal with heightened need among students for mental health support.

Cal Poly Humboldt students living in their vehicles amid a severe housing crisis found community in campus parking lot G11. But when the university ordered them off campus, their sense of safety was sundered.

Maria Gisela Sanchez Cobo, a counselor who has worked at Cal Poly Pomona since 2018, said she works on 12-month contracts with no guarantee of renewal from year to year. She’s watched co-workers leave the department for permanent and higher-paid positions elsewhere.

“It’s really hard to maintain a permanent mental health team to serve your students — people that stay here, grow, learn about the students’ needs,” she said.

Back at Cal State L.A., the variability of work weighs on Jay Conway, a lecturer in the philosophy department. In his ten years at the university, he’s taught up to five classes in a semester, or as few as two classes.

He makes mental calculations: three or fewer classes and he’s in “major trouble in terms of being able to pay rent and pay my bills.” To offset the loss of work, he scrambles to pick up classes at other colleges or universities, or racks up credit card debt for basic expenses such as rent.

With weeks until the next academic semester, Conway said it’s unclear how many classes he will teach. A recipient of the university’s outstanding lecturer award in 2017, he doesn’t know how much longer he can afford to stay in the system and is eyeing jobs in copy editing and policy work.

“I have students that go out of their way to tell me that the work I do here really means something to them. And that is such a priceless thing,” he said. “That’s the kind of thing that makes it difficult for you to leave, even when the place that you’re at doesn’t value you.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.