How one man’s wheeling and dealing brought the Olympics to L.A. and changed the city

- Share via

A group of the city’s power brokers gathered in Los Angeles to hear from one they’d dispatched to review the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam. It’s dire, he tells them, how much work there is left to do. There’s no way Los Angeles can accept the enormous costs and challenges of the 1932 Games.

But one man is missing — Billy Garland, subject of Barry Siegel’s new book, “Dreamers and Schemers,” and he is, the author argues, the city’s most important figure. So Los Angeles waits. No vote is taken.

Decades earlier, a young Garland fled the East Coast for what felt like a more even playing field in California, where roads in Los Angeles still used dirt. Soon he found his calling: real estate. Acquiring more and more dirt, he comes to believe with fervor that nothing matters more than who owns the land.

Garland is hard not to like. He cottons immediately to driving, challenging friends to join him on what turns into a five-week trek to drive a Pierce-Arrow automobile from Los Angeles all the way to the Atlantic. Along the way, he drops a wallet containing $6,500. Naturally, it’s returned. Garland, Siegel shows again and again, is charismatic, lucky and seemingly can’t lose.

Once back in Los Angeles, Billy Garland takes up his greatest challenge yet: What better way to show off his city’s charms than to host the Olympic Games?

The author of eight books, winner of a Pulitzer Prize for feature writing and director of the literary journalism program at UC Irvine, Siegel works hard to offer a gripping portrayal of Garland’s marathon campaign to get the Games.

The saga is wily and prolonged, and it’s a testament to Siegel’s chops that in all the machinations the story only occasionally gets bogged down.

We learn plenty about Garland’s relationships with the town’s newspapers and its film industry, and Siegel details the way both are galvanized to deploy whatever facts are necessary to persuade voters to grant permission and funding. There’s even an odd couple/buddy movie dynamic in the surprising and tender friendship between self-made Garland and the short but proper Baron de Pierre Coubertin, head of the International Olympic Committee, whose august blessings Garland needs to bring the Games to Southern California.

Probably the most appealing nugget of insight Siegel offers is the way the 1932 Games in Los Angeles changed things for athletes. The cost of coming to America from Europe — during the Depression, with fascism on the march — was always going to be an obstacle for Garland. So he strong-arms until the world bends, with hotels and railroads granting cut-rates for athletes, low enough to get even an Egyptian athlete here. (The Brazilians, Siegel reports, sell sacks of coffee on their way up, sailing to San Francisco and back until they have enough dough.)

Once all the contestants arrived, it was women — more female competitors were at the 1932 Games than at any previous contest — who stayed in a hotel, while the men bunked in special cottages erected on land donated by a Baldwin Hills oil tycoon.

This was the Olympics’ first purpose-built athletic village. It was not only affordable, but it brought athletes from dozens of countries onto one patch of land, with shared kitchens and showers and a sense that for at least a few weeks, the world could get along.

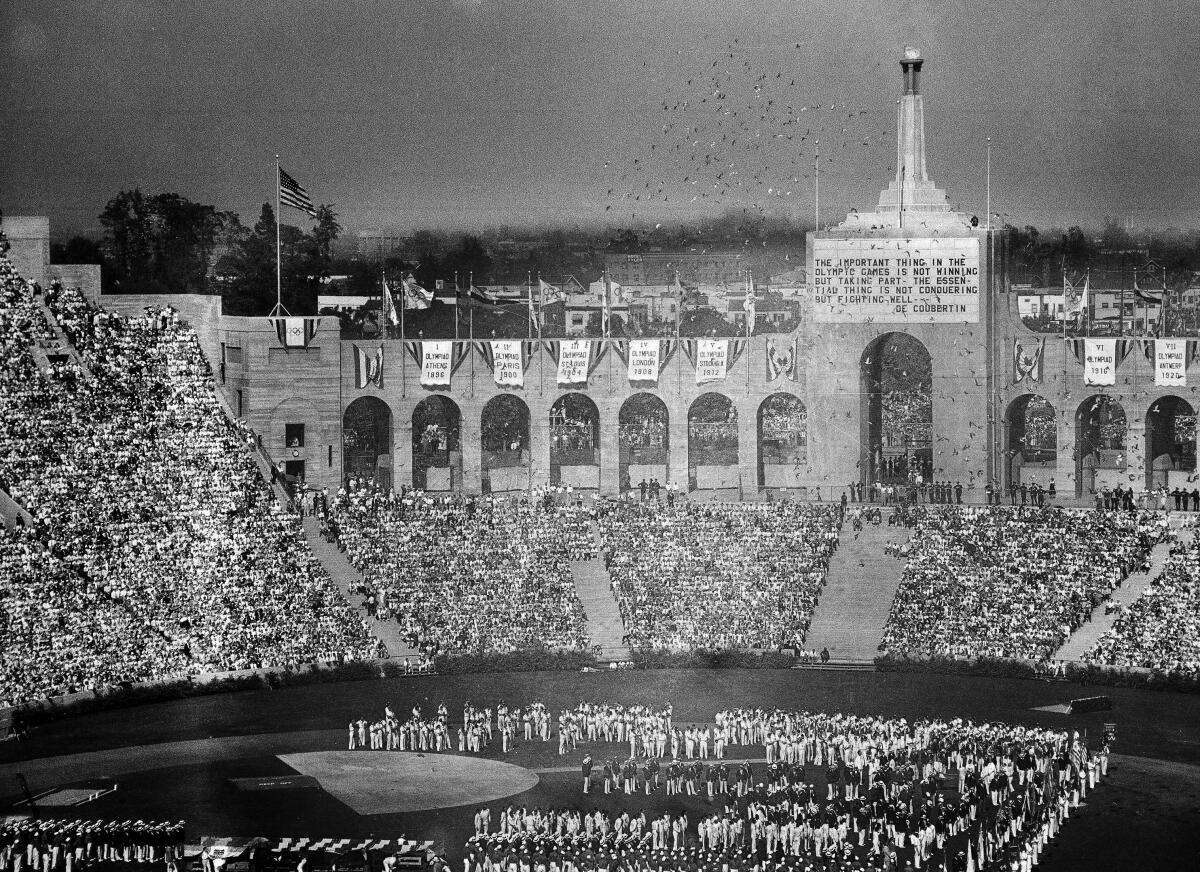

Endemic to books of this genre — heavy on historical documents, light on interviews with the living, a lot of weight put on old photos and imagination — there is some speculation. On the day the Games open in 1932, for example, we are told that Billy Garland “could not have been happier.” And that he surely saw the peaks of Mt. Lowe and Mt. Wilson sparkling “with clarity.”

Siegel, though, stays loyal to a larger, stated goal: to plumb with care and fondness the extent to which one man could overcome so many obstacles to do something epic, successful and with wide-ranging consequences for both a city and a worldwide athletic contest.

So the next time you go to the Coliseum, if you ever do, regard the plaque of Billy Garland. Maybe he broke some rules, perhaps his success is a product of a system that allowed rich white guys to do more or less whatever they wanted.

But in any case the 1932 Games nudged future Olympics in a more progressive and interesting direction. Siegel, a former Times reporter, contends that the Games forever changed Los Angeles too: Because of the infrastructure built, the visitors to the city (both athletes and audience), and all the attention the spectacle delivered in the form of news coverage, L.A. was set by Garland and the Olympics more firmly on the path to becoming one of the greatest cities in the world.

Barry Siegel

University of California Press: 272 pages, $29.95

Deuel is the author of “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.