How language can destroy or rebuild, per Times Book Prize fiction winner Ben Lerner

- Share via

Notable as a poet, Ben Lerner has in the last decade also published a trio of witty, topical, challenging novels that redefine what we want from and can expect of contemporary fiction. The first, “Leaving the Atocha Station,” referred to by critic Geoff Dyer as a “comet from the future,” was a savvy and moving assessment of Americans abroad and adrift after 9/11. His followup, “10:04,” moved the action to Brooklyn and Manhattan, where the author pondered indignities large and small, from bad lunches to Hurricane Sandy.

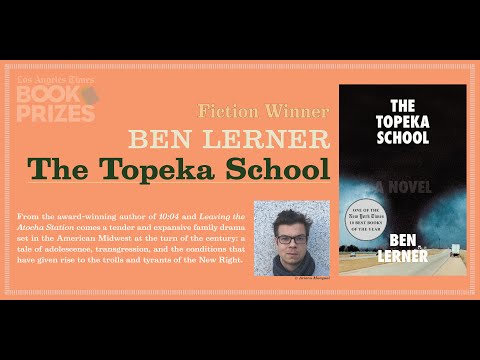

“The Topeka School,” winner of the 2019 Los Angeles Times Book Award for best fiction, deploys an even more potent arsenal of autofiction, erudition and dry wit. Set in the ‘90s, the story concerns three generations in Kansas, including a pair of psychotherapists and their champion debater son, and culminates in an act of violence that seems to change everything. It’s about the power of words, the worst we can do to one another and the durability of memory, family and protest. Lerner discussed family, manipulation and the pitfalls of empathy in a long email exchange.

At the heart of “Topeka School” is the bizarre art of speed debating, or “spreading.” How does it relate to what currently passes for, as your narrator Adam called it, “national political discourse?”

The book wants to locate something like hope — and not just horror — in the extremity of fast debate or even in Trump’s word salad. It wants to say that when a language collapses and becomes pure sound we are also reminded of our power to remake language, to refresh the social capacity for meaning-making. I think a lot about that phenomenon called “semantic saturation” — how if you repeat a word often enough it starts to lose its meaning. On the one hand, it’s scary — you feel the human world slipping away, language becoming noise. On the other hand, you are also reminded of the crazy miracle of language. New languages are always possible.

You were a champion debater. How did it shape you as a citizen?

I think debate for me kind of weaponized discourse, made it about winning and losing and point-scoring. In a way the adult Adam writing the book is at once horrified by “the spread” and sees it as a way these adolescents were pushing language to an extreme in order to reveal the emptiness of a lot of political rhetoric. He sees it as a kind of avant-garde poetry. I don’t think it made me any kind of citizen but maybe it led me toward literature?

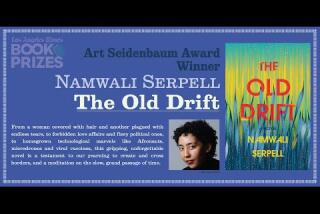

The 14 Times book prize winners, including Steph Cha, Namwali Serpell, Marlon James and George Packer, were honored in a virtual ceremony on Twitter.

The tragic character of Darren is a deeply vulnerable and also potentially scary figure. As a cerebral writer, how do you think about the smaller work of empathy?

I think empathy in fiction means both imagining other minds and acknowledging the limits of one’s ability to occupy the position of another. The italicized and peripheral sections written from something like Darren’s perspective are the older Adam’s attempt to imagine Darren’s vantage — there is never really the pretense to having unmediated access to Darren’s internal experience. The work of empathy is urgent, but if it passes into a kind of universalism or omniscience it can become a form of condescension or domination. I think the artistry is in trying to get the balance right: How do I identify with someone and also respect what’s unknowable about them? How do I respect that I can’t even know myself?

Another theme is the way parents have to both teach and trust their children. Now that so many of us are homeschooling, how are you feeling about that balance?

This is a book in part about remembering my childhood from my parents’ perspective now that I’m a parent myself. And undertaking a thought experiment like that for me has involved both incredible admiration (the book is really an homage to them) and the realization that they — like me — often didn’t know what they were doing. I don’t pretend to have any wisdom about homeschooling in a crisis. Luckily I am married to an incredible educator so I have someone to teach me.

Is there a young, emerging writer you want to highlight?

I was recently taken by the Mexican novelist Fernanda Melchor’s novel “Hurricane Season.” Just today somebody sent me some very powerful poems by a poet out of Michigan named Jonah Mixon-Webster. I’m fond of Emily Skillings’ poems. I encounter scores of great emerging writers through teaching.

The classic Gelett Burgess poem “The Purple Cow,” featured in “Topeka School,” seems oddly perfect for the bizarre world we live in now. Some isolated readers seem to be finding solace in poetry. What’s your take on how poetry might offer us guidance?

The poem is really important in the novel. Adam’s mother, Jane, learned it from her mother and passes it on to Adam — but (the child) Adam and Jane play a little game of misquotation in which Adam always inserts errors into the poem and then Jane, pretending to be exasperated, corrects him. Jane is passing something down, but she and Adam are also making it their own, showing how the patterns of a family, like the patterns of the poem, can be broken and remade. So a nonsense poem becomes really important for them, full of meanings they can’t otherwise speak. A poem can be a meeting place where we find and make and share meaning and watch those meanings change and multiply. Poems circulate between the living and the dead too. They suggest a different relation to time than the perpetual present of the news.

Deuel is the author of “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.”

Los Angeles Times Book Prize winners

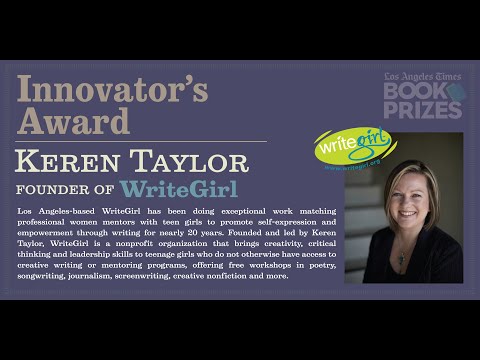

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Keren Taylor, Innovator's Award

2:04

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Namwali Serpell, Art Seidenbaum Award

1:51

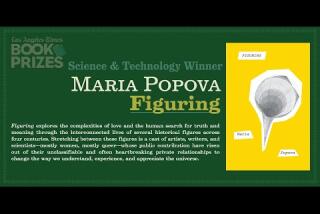

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Maria Popova, Science & Technology

3:09

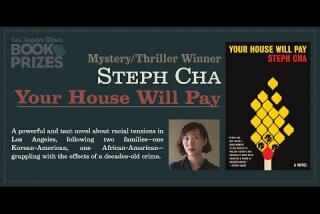

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Steph Cha, Mystery/Thriller

1:33

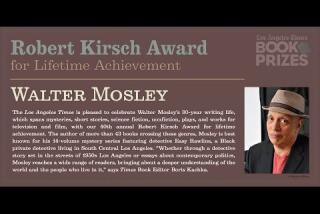

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Walter Mosley, Robert Kirsch Award for Lifetime Achievement

2:27

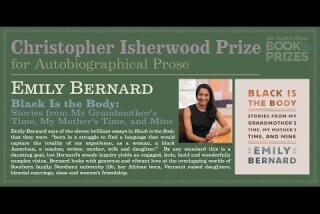

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Emily Bernard, Christopher Isherwood Prize for Autobiographical Prose

1:43

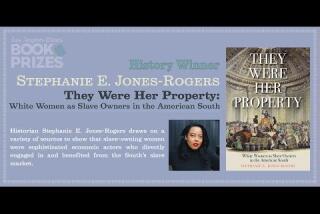

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, History

1:35

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Ben Lerner, Fiction

1:11

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Emily Bazelon, Current Interest

0:42

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Eleanor Davis, Graphic Novel/Comics

2:00

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.