Novelist Tayari Jones braves COVID-19 and voter suppression in Georgia

- Share via

For months, the Times has been asking writers to tell us what they’re seeing, hearing and doing in quarantine. Over the past few weeks they’ve been emerging to address another national emergency, racial injustice. Tayari Jones, whose bestselling novel “An American Marriage” was an Oprah’s Book Club selection, was worried for her older parents, but emerged from COVID quarantine in order to cast her vote on Election Day in Atlanta. After a wait of nearly four hours, she visited her parents for a distanced catch-up.

Authors like Lionel Shriver, Alexander McCall Smith, Laura Lippman and Steph Cha are under coronavirus quarantine too. Here’s what they’re reading.

Tuesday, June 9, morning

It was Election Day in Georgia. I will admit that I am not a “super voter” who comes out for each and every election. I show up for the presidential but I’m spotty when it comes to the local, between-year races. Maybe this is because for much of my voter-eligible life, I have lived in temporary homes, chasing the gigs that made my life as a writer possible. Over the last 30 years, I have lived in a dozen cities, never putting down roots.

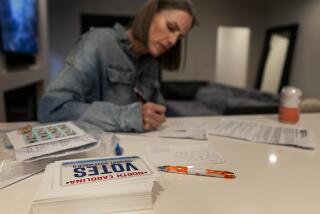

Now I have returned to Atlanta, my hometown. Even before I unpacked the first box, I registered to vote. Knowing that I would be on book tour in November 2018, I opted to vote absentee. I’d heard rumblings about ballots being thrown out for minor issues, so I was extra careful as I checked the box beside STACEY ABRAMS for governor. I scrutinized everything several times before sealing the envelope, and even affixed an extra stamp.

But this is 2020. Stacey Abrams is not the governor of Georgia; Brian Kemp is. And Gov. Kemp installed new voting machines just in time for this election. Word on the curb is that no one knows quite how to work them. And have I mentioned there is widespread civil unrest? Here in Atlanta, police officers have been fired for brutalizing protesters. In addition there is the matter of a global pandemic. And from what I have read and observed, being Black is a significant co-morbidity.

When it comes to social distancing, I have been extremely vigilant. My parents, ages 77 and 84, depend on me. If I were to expose them, I could never forgive myself. Luckily, they toe the line too, wearing the three-ply face masks my mother designs and sews herself.

Last week, Atlanta was on fire with protests and straight-up rebellion after the murder of George Floyd. From my patio I heard muffled explosions. Tear gas? Gunshots? Who knows. Secure in my home, I turned on CNN and watched the brave citizens facing down the police and COVID. The next morning, I contributed to various bail funds. On Election Day, I woke up with a little bit of fire in my belly. Before bed, I watched video of the crowd in Bristol, England, pulling down the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston and shoving it into the harbor. Even though this act of radical civil disobedience was happening across the ocean, it reassured me that Diaspora is real. As I dressed, I chanted, “They drowned it!” as a mantra and affirmation.

My friend Jewell is one of those savvy millennials who knows this city even better than I do. Following her advice, I packed a bag with water, snacks and a book. “It’s going to take a while,” she said. “And it might rain.”

The voting line looked like America: a multiracial cohort, determined to exercise its constitutional right. When I arrived, the queue was about five blocks long — and not because of social distancing. Several people sat in camp chairs like the one I happen to keep in my car. I slung it over my shoulder and traveled to the tail of the line.

Here in Georgia, folks talk to one another. There is no way we are going to wait behind 200 people and not complain or rib about it. The problem is that face coverings make it hard to chat. Nonverbal communication would have to do. Raised eyebrows and a shrug meant, “Isn’t this ridiculous?” Narrowed eyes and a shake of the head communicated, “This is voter suppression.” Narrowed eyes, lowered brows and a tight jaw said, “Stacey Abrams should be governor.” Finally, our shoulders slumped with the weight of all the objections unexpressed and just the small talk we were forced to swallow.

Who is Stacey Abrams? Many put her on Joe Biden’s list of possible vice presidents, and she says she would make an ‘excellent running mate.’

Atlanta is hot in June, and humid. Two hours in, the air grew even thicker as heavy rain clouds elbowed out the sun.

The young woman behind me took her mask off. With her sweet-tea accent, she fussed. “I am so tired of smelling my own breath. I would pay $3 for a peppermint!” A woman in a chair like mine looked up from her knitting, stuck her needles in her Afro, rummaged in a BLM tote bag, then offered the candy like a church lady. I, too, was sick of breathing my own air, but I didn’t want to seem grabby.

A white guy on a vintage bicycle — complete with basket and bell — offered to construct a poncho from a garbage bag. “Don’t let the rain chase you away, ma’am. Don’t let them steal your vote.” It was almost 90 moist degrees, but I said, “Yes please,” because I appreciated his efforts and I didn’t want to hurt his feelings.

At last I made it to the (blessedly air-conditioned) polling place. I had researched the roster of candidates, saving my choices on my phone. How was I to know that electronics were not allowed? If I wanted to consult my phone to refresh my memory, I would have to return to the end of the line.

Frustrated almost to the point of tears, I studied the ballot, trying to recall my selections. I hoped I was voting for the right people, and then it was over. I accepted my peach sticker and affixed it to my mask. As I trekked to my car, the clouds spit and sputtered. I offered my plastic poncho to a man still blocks away from the polls.

“How long did you wait?” he asked.

“Almost four hours.”

He sighed. “I’ve been here that long already.”

Evening

Exhausted and sticky, I was home, eager for a cool bath and a white wine spritzer. My phone pinged. Mama wanted to know if I had received her grocery list. I slammed a double espresso before gathering the food and supplies my parents would need this week.

Before delivering the groceries, I removed them from the plastic grocery store bags and toweled everything down with precious Clorox wipes. Then, I transferred it all to clean canvas tote bags accumulated from my years of attending conferences and festivals. When I arrived at my parents’ home, they were waiting. I unfolded my camp chair but it started to rain. My mother’s face fell. She had been looking forward to a yard visit with me all week. Daddy entered the garage carrying three cans of Coke in his large hands. “Oh no,” he said as the rain came down in sheets.

I had an idea. I opened the hatchback of my car and perched in the trunk while Mama and Daddy sat in the open garage.

“Did you vote?” Mama asked me.

“I chickened out,” Daddy admitted. “This COVID is serious business for us old folks. Can’t take chances.”

I pointed at my Georgia Voter sticker. “It took all damn day.”

“Good,” Daddy said, smiling in the rain. “Voting is important.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.