Bureaucracy noir? Japanese novellas wring soulful suspense out of cop office politics

- Share via

On the Shelf

Prefecture D: Four Novellas

By Hideo Yokoyama, trans. by Jonathan Lloyd-Davies

MCD: 288 pages, $17

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

It shouldn’t work, what Hideo Yokoyama is doing in “Prefecture D.” The four novellas here occupy unlikely territory for detective literature: not criminal investigations per se but the internal machinations of a large metropolitan Japanese police department. Anyone who’s been an administrator knows there’s not a lot of overt drama in it, but for Yokoyama, that’s the point. He is interested less in the action of crime fiction — its menace — than in the atmosphere of police bureaucracy, the way his characters deal with office politics and protocol. “Whenever frontline members of the executive did something to cause a loss of face,” he writes early in “Season of Shadows,” the first of these brisk and unexpected mysteries, “… [y]ou had to avoid transfers that were an obvious step-down, that would risk catching the attention of the press.”

What Yokoyama is describing is crisis management, the forte of inspector Shinju Futawatari — “thin, resembling a banker more than an officer of the law, unsure even of how to make an arrest.” Futawatari is a career functionary, in other words: an invisible man. All the same, he becomes an investigator of sorts after Michio Osakabe, a former director of Criminal Investigations, refuses to retire. The act — a disgrace in the tradition-bound department —sends shockwaves through administration, requiring Futawatari to become involved. “The sense of defeat was absolute,” Yokoyama writes, after an attempt to interrogate Osakabe fails. He is referring not only to Futawatari’s feeling of being overmatched but also to a dynamic at work in every police department, where investigators and their bosses distrust each other across an organizational divide.

This mutual antipathy infuses the novellas in “Prefecture D,” which circle one another although they are not continuous in any direct way. Futawatari makes a few cameos throughout the book, and other characters recur as well. The point, however, is less that things add up than that they never do. Describing internal affairs investigator Takoyoshi Shindo in “Cry of the Earth,” Yokoyama observes, “As a fellow officer of the law, his was work that felt good. It was the disciplinary side that was the challenge.” The job of policing one’s colleagues provokes a feeling of displacement, of the outsider looking in, which is a hallmark of contemporary crime fiction. It is a point of view Yokoyama shares. His characters are not lost but adrift, swept up in inner longing, dissatisfied with or even broken by many of the aspects of their lives.

Writers Rachel Howzell Hall, Attica Locke and Ivy Pochoda talked with Times reporter James Queally for a 2020 Los Angeles Times Festival of Books event.

Shindo, for instance, has lost half his stomach to an ulcer; he is literally eating himself from within. A similar uneasiness afflicts Section Chief Tomoko Nanao, who in “Black Lines” must probe the disappearance of one of her officers, the young forensics investigator Mizuho Hirano, after she fails to show up at work one morning. Nanao’s inquiry is hindered by the misogyny of the department. As a male officer dances around his doubts over Hirano, Nanao mentally finishes his sentence: “she’s a woman, so who’s to say what she’s really thinking?”

For Yokoyama, the department is first and foremost a political landscape, made up of different constituencies. That makes his work a kind of social fiction, excavating the most secret of societies, the police. We see the fallout of this secrecy at the end of “Black Lines,” when (spoiler alert) Nanao is forced to stare down the hypocrisy of the police force after discovering Officer Hirano at her parents’ home, where she has fled after being shamed at a crime scene by a male higher-up.

“It was unnerving,” Yokoyama writes. “… The corridor seemed to shrink around her. Tomoko picked up speed, her shoes clicking loudly on the floor. She took off her ring and held it tightly in her fist. For the first time, she understood she had no choice but to make superintendent.”

What’s fascinating is that these investigations are less about legality than propriety — or more accurately, the status quo. Nowhere in “Prefecture D” does anyone break the law, although Osakabe comes close, driving another man to suicide. (That said, his target was a rapist and a murderer.) “To live outside the law,” Bob Dylan once sang, “you must be honest,” yet these characters not only follow the law but enforce it. What is justice, then, and how does it operate? How do we make sense of right and wrong?

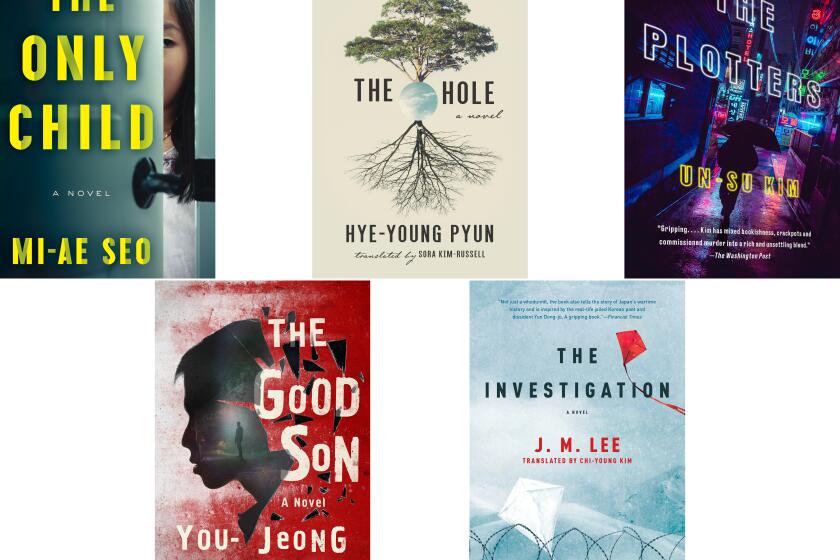

Five authors of Korean thrillers you should be reading: You-Jeong Jeong, Un-Su Kim, Young-Ha Kim, J.M. Lee and Hye-Young Pyun

Nowhere do such questions become more trenchant than in the final novella, “Briefcase,” in which an assemblyman from “the second-largest conservative faction” in the prefecture threatens to ask questions in a public forum that would embarrass the police. Administrative officer Masaki Tsuge is assigned to gather information, but this is a MacGuffin; the real drama involves his own domestic life. Tsuge has a son, an 8-year-old named Morio, who is being bullied, which reawakens memories of his own youth. “For a total of nine years in primary and secondary school,” Yokoyama writes, “Tsuge had been controlled by a boy with snake eyes. He didn’t doubt that he’d looked anxious too, just like his son did now.”

Here, the focus tightens from the social to the personal, revealing the humanity beneath the law’s facade. In a way, this echoes the first novella, “Season of Shadows,” in which Osakabe is driven to act after his daughter is assaulted. The difference is that Osakabe is able to direct his grief and anger outward, whereas Tsuge can turn on no one but himself. “Make one friend,” he thinks to tell his son. “Just one will do.” Even those few words are not enough. “He wasn’t sure if he really believed them,” Yokoyama acknowledges, “but he pushed down on the accelerator regardless, as though to stamp out the apathy growing inside him.”

This is the dynamic with which we are left to reckon, somewhere between indifference and hope. We need to believe in something, Yokoyama insists, whether the order of institutions or the stability of family. And yet there is only so much we can do. For the characters in these novellas, caught up in their amorphous investigations, police work is perhaps most important for the structure it offers, a way of giving shape or meaning to their days. What makes them recognizable and human is that this is not enough, that it can never be enough.

In ‘Scandinavian Noir: In Pursuit of a Mystery,’ the critic travels to Nordic cities to investigate the society that shaped a global phenomenon.

Ulin is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.