How a long-ago murder shaped Antoine Wilson’s life and his dark, twisty L.A. novel

- Share via

On the Shelf

Mouth to Mouth

By Antoine Wilson

Avid Reader: 192 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Murder is never far from Antoine Wilson’s mind.

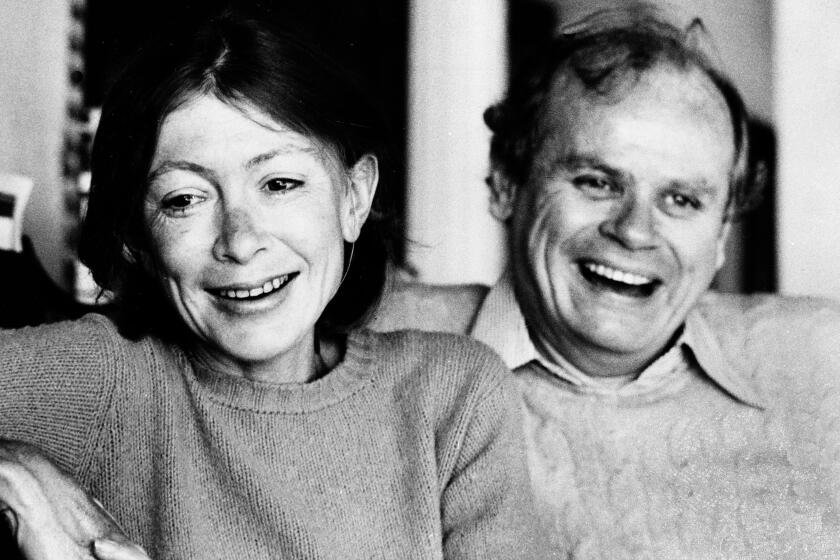

The author of “Panorama City,” “The Interloper” and this month’s novel, “Mouth to Mouth,” loves to talk about his family. His wife, Chris, is a Hollywood screenwriter who has worked on “Law & Order,” and Chris’ late father, producer Richard Levinson, co-created classic shows like “Columbo” and “Murder, She Wrote.” Wilson also talks openly about the real-life murder that broke his young life apart (and then became a true-crime staple). The effect this has had on his fiction isn’t always as close to the surface, but it’s always there.

“Mouth to Mouth” has overtones of a murder mystery, though it is more of a caper crossed with a moral parable told by an unreliable narrator. Whether it is about a murder is, well, up in the air. Perspective is everything, as Wilson demonstrates during a Zoom call from his home office in Brentwood, when he turns off his blurred background and reveals himself surrounded by mounds of tinsel and torn giftwrap — the detritus of holiday season.

The novel opens, in a neat framing device, with an airport encounter between an unnamed narrator and an estranged friend, Jeff Cook, from the narrator’s college days at UCLA. Twenty years after graduation, the two men couldn’t be more different. The narrator is flying economy and accepts the invitation to join his old acquaintance in a first-class lounge, where Jeff begins to spin a circuitous tale about the time he saved a man’s life on a Santa Monica beach using mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Revived, the man doesn’t thank him, and Jeff wants to understand why.

It turns out that the man he rescued is a well-known Los Angeles art dealer named Francis Arsenault, and Jeff seeks him out. Whether the rescuer is longing for attention or something more transactional doesn’t matter by the book’s midpoint, when he’s secured his place as not only Arsenault’s deputy (and thus a key broker in the cutthroat world of fine art) but the beloved of Arsenault’s beautiful, unstable daughter Chloe.

S.A. Cosby’s “Blacktop Wasteland” stakes out territory in undersung places — and sings too of the complex lives of Black men.

Jeff’s tale takes some more wicked turns, dizzying reversals of fortune leading to a final twist that raises questions about culpability, truth, evil and even the moral weight of a human life. It’s a long road for a short book, and it took the author a long time to get there.

Wilson grew up in Montreal, the youngest child of a successful surgeon “who had many sons,” he says. “Three with his first wife and three with his second, my mother.” When Wilson was 7, his father decided to move his second family — a lot: Fresno, Santa Monica, Saudi Arabia, back to Santa Monica. One of the reasons for the frequent moves was the 1978 kidnapping and murder of Wilson’s half-brother, Eric.

“He was 19, and he was driving across the country to visit us,” Wilson says. “His Volkswagen bus broke down, and a couple of drifters helped him fix it in exchange for a ride. They stole the bus and murdered him because they didn’t want a witness to the theft.”

Wilson relates the story plainly but looks down as he continues. “He was missing for months. It was awful, the atmosphere so tense at home. There was a documentary made about it by John Zaritsky called ‘Just Another Missing Kid,’ shown on a Canadian series called ‘The Fifth Estate,’ kind of like our ’60 Minutes.’”

He takes a breath. “It won the feature documentary Academy Award a few years later. It’s weird. What did I understand? I understood that he’d been murdered, that he was dead, and there was a sort of wake for him, but there was no body. Not until I was an adult did a lot of that hit me, could I bring my own life experience to bear on those facts.” At the time, it was more than the “little French Canadian boy” could comprehend — let alone the transformation of his brother’s death into a television event.

Joan Didion, who died Thursday, left a seismic impact on the literary world and her home state of California.

Wilson made his own cross-country drive years later, to graduate school at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. On the way, he accidentally stopped “in North Platte, the worst possible place, because that’s where Eric had been when he met the drifters.”

His brother’s killer, Raymond Hatch, was out on parole at the time. “I thought, ‘What if I went to the hotel bar and sat down and had a drink and Hatch was right next to me?’ He’s dead now, but you ask yourself, ‘Would I put a cap in the head of someone who murdered my sibling?’ Yeah. I could probably do that.” He muses that the experience left him with two questions: What is justice, and are there people who just shouldn’t receive the benefit of the doubt? It was the start of another journey for Wilson, reckoning with his family’s loss through fiction.

He wrote a short story at Iowa about the murder, “a commingling of memory and imagination of that time.” But his novels would go on to probe those larger questions — about justice, goodness and retribution. His 2007 debut, “The Interloper,” follows an unhinged narrator bent on avenging the murder of his brother-in-law. It includes the line, “It’s the noblest mistake to see the humanity in everyone” — which novelist Jess Walter quoted in his review of the book for The Times. Wilson’s 2012 follow-up, “Panorama City,” took a different tack; as Adam Ross wrote in the New York Times, “The author’s gaze is directed heavenward, toward sanity and the good in all of us.”

“Mouth to Mouth,” I suggest to Wilson, marks a return to skepticism about humanity, himself included. He acknowledges that as a fair observation — and refers again to his somewhat unstable upbringing. “I’ve had to become adaptable to different environments and social situations,” he says. “Some people are just strange, right? I grew up feeling that I was not particularly normal, but I really wanted to belong. I’m just glad some people who wrote in my seventh-grade yearbook said I was a nice guy.”

Could any character in “Mouth to Mouth” be described as “a nice guy”? Wilson says Jeff wants to believe he is, “and that’s sort of at the center of the book. You can imagine Jeff coming home and singing ‘How did I get here?’ like The Talking Heads.”

Bethanne Patrick’s January picks cover train wrecks, political drama, enraging inequality, the complications of polyamory and the joy of the ampersand.

Wilson isn’t sure how “Mouth to Mouth” got here but he knows it was a long time coming. Cleaning out his computer recently, he found a file: “AirportStory.TXT.” “It describes a name being called over the PA system like Jeff’s is for the narrator; the bio of an art-world person I knew a long time ago; and the image of fireworks from above that winds up on the first page. Just those three things, from 20 years ago, that had been circling in my brain ever since.”

The premise of a man ungrateful to his rescuer also goes back decades: “In the late 1990s, I stopped a man from walking in front of a train. He wasn’t doing it deliberately, but I did save his life, and he said, ‘I’m gonna buy you a big steak dinner!’ Then the train went by, he kept walking, and that was it. I never got my steak dinner!” Wilson laughs. “It’s an interesting moment, when people intersect that way. Unlike murder, it’s not a taboo, but it has the same kind of power. What do you owe someone who saves your life?”

Such dilemmas are the engines of fiction. As for murder and all its entertainments, Wilson is understandably more ambivalent.

“In my wife’s childhood home,” he says, “there are books about murder everywhere, and that has to do with character, who people are when faced with the highest stakes imaginable. But having experienced my brother’s murder? I still don’t love true crime.”

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.