A debut novel of love and privilege that’s made for TV

- Share via

On the Shelf

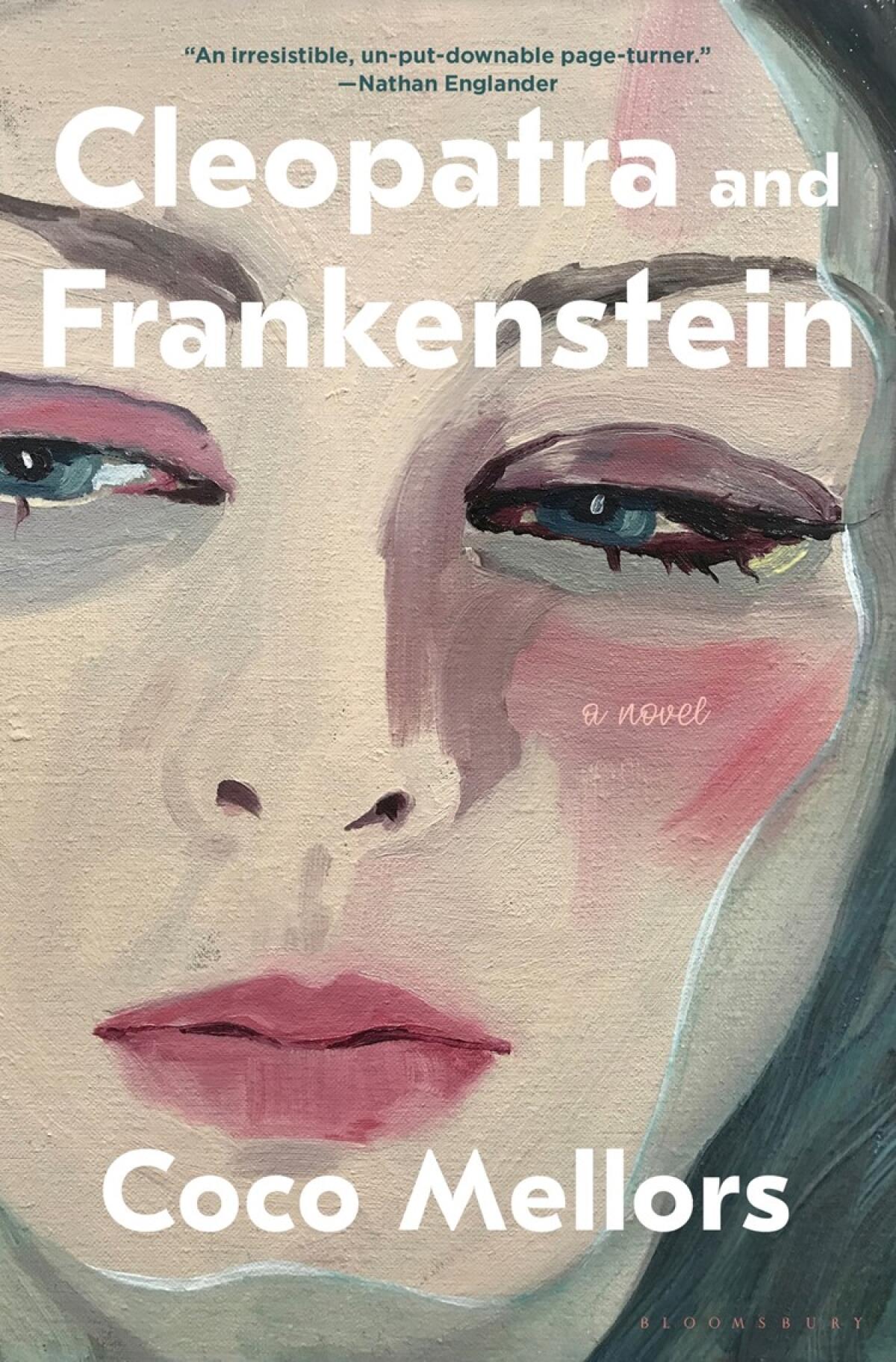

'Cleopatra and Frankenstein'

By Coco Mellors

Bloomsbury: 384 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

If Manhattan were a drug, which one would it be? This is one of the profound questions raised by reading Coco Mellors’ tantalizing but blithe debut novel, “Cleopatra and Frankenstein,” whose Manhattanites run on stimulants and drown in alcohol. Hers is a city of flash and fluttering movement, as if deliberately designed to distract its inhabitants (or those Mellors chooses to depict) from seeing that, beneath the surface, there’s no there there.

Cleo — beautiful, blond and British — meets Frank — older, handsome and an award-winning advertising executive — in an elevator 90 minutes before the first day of 2007. They’ve both left a New Year’s Eve party. Their first conversation turns into an exchange of witty remarks that leads to dinner and flirtation.

The next scene opens on the couple’s wedding day. It’s a scant six months later, and the pair’s friends are as surprised as the reader. It’s a daring leap for the lovers and also for Mellors, her fast-forward a clever way of rendering courtship as a heedless blur, the details only coming into focus once a marriage has set (or curdled). Whatever has passed between Cleo and Frank — dates, arguments, a proposal — has occurred off the page. This second chapter, the wedding reception, provides an extended party scene that introduces the supporting players who populate the novel.

The younger characters are all creative and struggling to find themselves. The older ones are “people who had found the intersection between creativity and economy, who made beautiful things but did not suffer for it.” Many of the guests have flown into Manhattan from different parts of the world, carrying origin stories and ethnicities that do too much of the work of explaining who they are. And while some are temporarily broke, no one is poor. Trust funds and inheritances shelter them. Even for those without support, it’s a shabby-chic life.

The seven deadly sins of bad art friendship, fleetingly explored in a debut novel

Episodic chapters titled to mark time’s passage are narrated in the third person — until we get to “October,” wherein a woman named Eleanor tells her own story. The vignettes that open Eleanor’s chapter feel like a comedy routine, albeit tempered by sadness over a beloved fading father. Eleanor is not beautiful. As she prepares to go to a company function one night, she stands before her mirror and sees “soft belly, coarse hair, thin lips, thick waist. I am a Jewish man in drag.”

In what I’m worried is not a coincidence, the book’s clearest outsiders are two of the non-WASPs: brainy, unattractive Eleanor, the anti-Cleo, and Santiago, the overweight, unpartnered Peruvian. It’s hard not to think of them as magical minorities, helping the messy beautiful white people see themselves more deeply.

A more fundamental concern is how easy it would be to imagine this pre-recession Gotham universe as a Netflix series. The city’s surfaces are attended to in cinematic detail; emotional connective tissue often consists of characters telling their friends about their awful childhoods and narrating character traits direct to camera. (A recent Times of London profile, after breathlessly proclaiming, “Move over Sally Rooney,” noted that Mellors is “already in discussion with several streamers.”)

The relationships themselves rarely feel lived-in. Frank’s younger half-sister, Zoe, is frequently mistaken for his wife because she is Black — their mother remarried a Black man. There are deep similarities beneath the surface, but Zoe describes them in broad strokes that feel like script character notes: “Their mother might not have made her offspring in her image, but she had stamped them with her nature, a fact they both deeply resented. Quick to love, quick to anger, quick to self-destruct.” Internal emotions are described in similar ways — voice-overs clumped at the ends of chapters sharing how a character had “really” been feeling.

Wilson’s third novel, ‘Mouth to Mouth,’ is a taut, heady thriller narrated by a man who saved another man’s life and wouldn’t let him forget it.

Maybe this comes down to a lack of social context. The servers who support the characters’ lifestyles are barely remarked upon. The homeless or the “gypsy” begging in the street are objects of distaste. And the voyage of discovery is taken along a river of self, with society and its greater problems hidden away along the banks. With the exceptions of Eleanor and Santiago, Mellors’ characters ignore the outside world. It isn’t clear whether the author intends this as social critique.

This is Mellors’ debut novel, and it’s clear that she knows a world built on flash and substances (but not substance) is bound to crumble. She has written some extraordinary sentences and shows a great talent for dialogue. And she cannily sets Gen X artists who found a way to combine art with commerce against millennials who were raised to grasp at shiny objects that wound up beyond their reach. Her party scenes play out the inevitable clash: youth and money, mutually envious. Redemption for some of her characters will come with the recognition that the envy is misplaced and that developing a sense of self means reaching for higher-hanging fruit.

There’s nothing wrong with writing books that are ripe for adaptation. Literary fiction is full of critically adored authors who hustled other jobs to pay the bills, and novels turned into series have given us some of our greatest television. But the type of enlightenment presented in certain novels, in which easy access to money makes chasing one’s art a matter only of finding oneself, ignores a world on fire with chaos and inequality. And it tends not to make for great TV either.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

Author Emily St. John Mandel was not involved in the adaptation of her hit novel. But series creator Patrick Somerville had her blessing to change it.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.