Allegra Hyde’s climate-fiction narrator is the post-cynical heroine we need

- Share via

On the Shelf

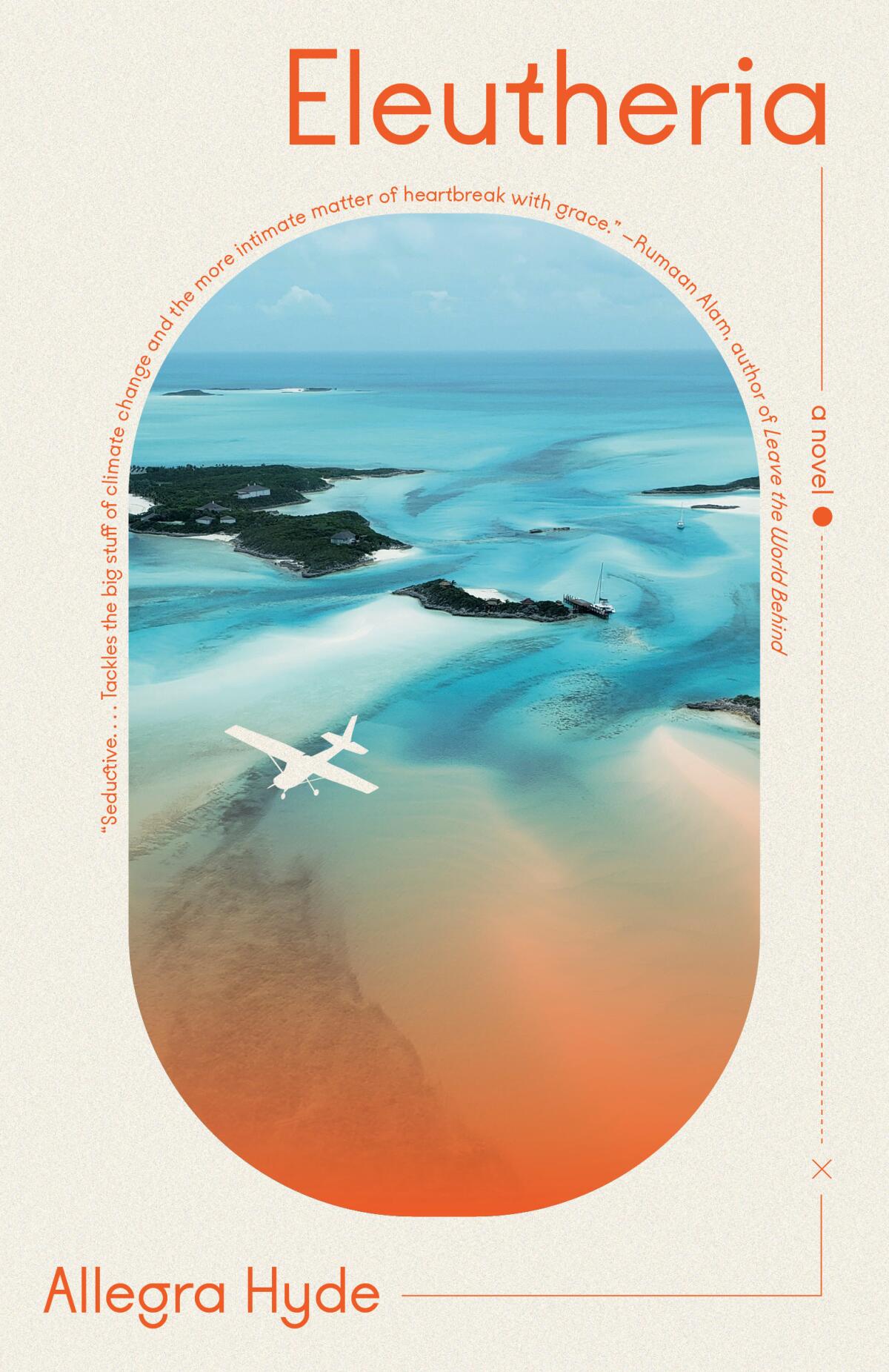

Eleutheria

By Allegra Hyde

Vintage: 336 pages, $17

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“I was obsessed with the notion of a poem as a kind of social grenade,” declares a major figure in Allegra Hyde’s “Eleutheria.” She and her creator both, I’d say. Hyde plants all sorts of IEDs in her first novel, shattering her protagonist’s heart, the streets of a decidedly un-United States and, especially, our fragile planetary ecosystem. This is cli-fi even when it turns intimate, with the first kiss between lovers or the failures of addict parents. Individual tensions generate unexpected crackle, but everyone’s caught in the same toxic knots, their environment collapsing around them. The upshot is a first novel way outside the norms: a work of imagination rather than autobiography.

The author indulged a similar inventiveness in her prizewinning 2016 set of stories, “Of This New World.” A number of those took a man’s point of view, even delving into their feelings about sexual dysfunction, and one piece went to Mars. Hyde’s first full-length fiction stays on Earth but often smacks of sci-fi. The setting is a near future in which American democracy is fraying as badly as the world’s habitability, and if the trope seems familiar by now, in “Eleutheria” it’s imbued with rare vividness. One startling scene trashes the streets of Boston with a mass die-off:

“Around noon, the birds dropped from the sky like feathery rain. Their small bodies thumped onto windshields … splashed into the Charles. They did not perk up and fly away.”

Disturbing as the material is, Hyde ups the impact with a flourish like “feathery rain,” and with sensory verbs: “thumped,” “perk up.” She’s always jangling the nerves, even when the focus shifts to the psyche. When the novel’s narrator, Willa Marks, orphaned in her teens, leaves rural New England to live with Boston cousins, she’s “overwhelmed” by “the brick-built topography,” like “a giant fireplace poised to burn me alive.”

Lydia Millet, whose latest novel, “A Children’s Bible,” tackled climate change, reads new fiction on climate and argues against calling it a genre.

Willa is the tinder in that conflagration. The action grows dreadful, the poisoned biosphere just about kills democracy as well, but the major events take place when Willa’s only 22, and she can’t help but relive how she got here: coming of age in a world that holds less and less promise. The deepening gloom has everything to do with her parents’ early demise. To avoid such a fate, Willa mustn’t lose her will; she must make her mark.

In finding validation, she also enjoys a sexual awakening, an affair with the older Sylvia, a Harvard professor but no simple predator — just as Willa is no clueless student. The depths and disruptions of their relationship, however, emerge only in flashback. The novel begins when Willa, trying not to think of Sylvia, instead “drunk on ideas,” flies to the Caribbean island of the novel’s title (Hyde prefers an archaic spelling). There she wrangles her way into Camp Hope, a utopian compound, full of strapping young elites committed to “living the solution” and “saving the planet” but also strangely secretive, its participants blindly unquestioning.

In these opening scenes, as Chekhov would say, the grenade’s hung on the wall; thereafter “Eleutheria” shows us how Willa came to pull the pin. A rough childhood has left her with an “innocent recklessness,” as Sylvia puts it, as well as a savviness about “the fumes of the American Dream.” Down on the island, she soon noses out the camp’s potential for corruption, and so the Bahamas chapters sustain as much momentum as those set in Boston. Both settings are rocked by tremors of a “chaotic time.”

From the acclaimed author of novels and short stories, ‘Harrow’ is a magnificent, moving story about people picking up the pieces of apocalypse.

The novel interleaves the narrator’s history with snippets of the island’s. Two or three pages at a time, in an alternative font, we visit the colonial past itself strewn with dead birds and the corpses of slaves. The same bell tolls, though with different vibrations, in the passages from the manifesto of the Camp Hope founder. Those lines feel bullhorn-ready, all about “the WAR against climate change,” while the brief takes on the archipelago’s history indulge the baroque rhetoric of the 17th century: “a cave open wide as a scream.” Both voices, however, offer crackpot visions of a New Heaven, a New Earth, unmistakably doomed. Both turn out disastrously unworkable; dystopias of the past and the future that together cast a chilling shadow over our present.

Striving for better, Willa’s primary tool is that recklessness, “too wise for cynicism.” The young woman revives that weary term “pluck” as she struggles to rescue various projects from their own worst impulses. Her Camp Hope effort fails, in a climax that reels from slapstick to horror, but the vision of a sustainable world may be redeemed by a fortitude not unlike Willa’s, a kind of Children’s Crusade.

That last imaginative leap is one of Hyde’s most spectacular, but if you ask me, her act only falters in its portrayal of the Camp founder, a standard-model megalomaniac. The rest of the secondary cast, however, all enjoy moments of subtlety, and overall “Eleutheria” achieves a remarkable humanity for a work that sets off global alarms. Hyde knows her title comes from the Greek word for “freedom,” and knows as well that few concepts have been so perverted, so polluted. That maddening paradox enlivens everything here, “caught in the slipstream of idealism and exploitation, the secret crux of the Americas.”

Domini’s latest book is a memoir, “The Archeology of a Good Ragù.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.