How one novelist built a world without prisons that’s even crueler than ours

- Share via

On the Shelf

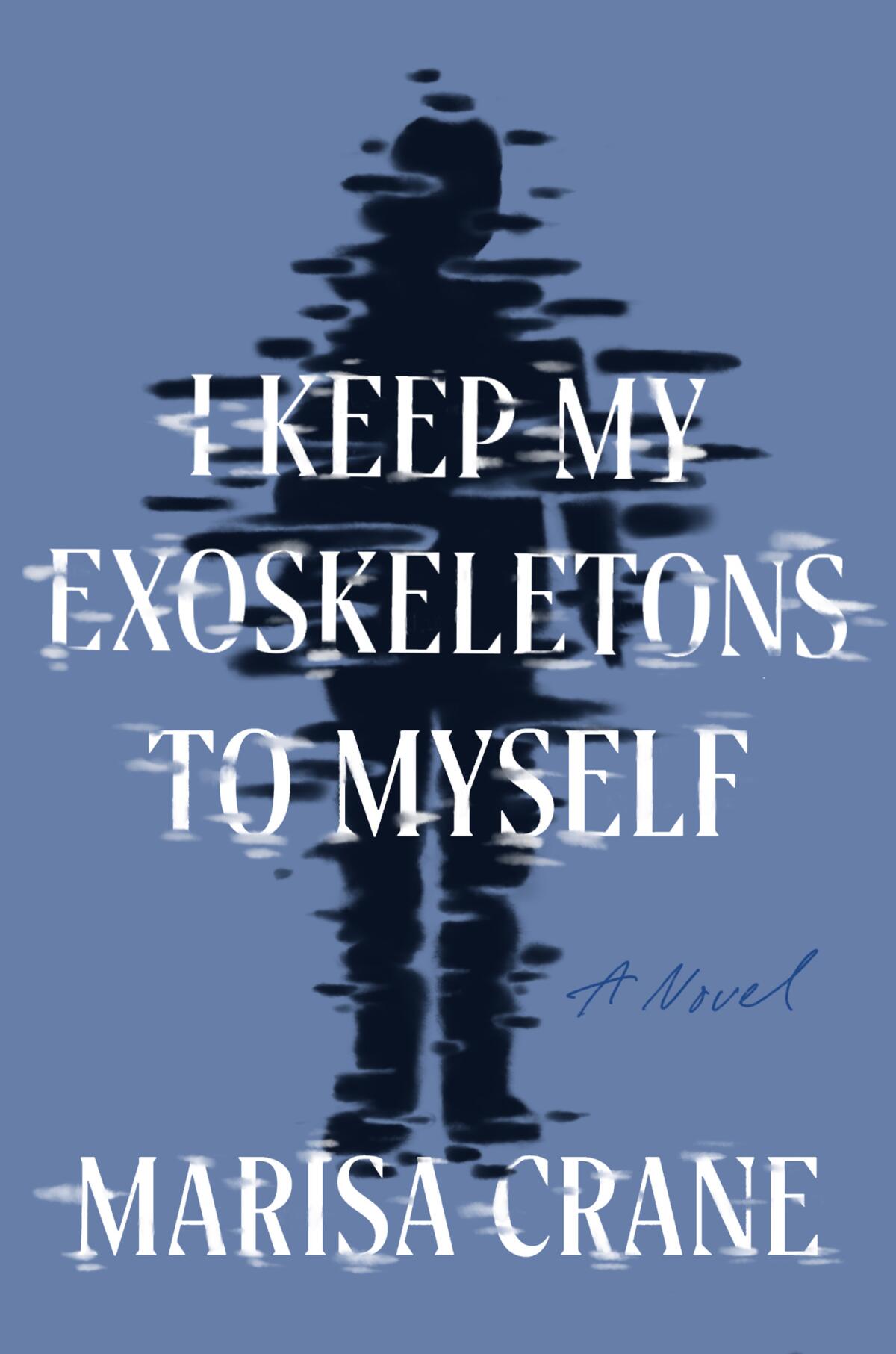

'I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself'

By Marisa Crane

Catapult: 352 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Marisa Crane was an athlete virtually from birth, picking up basketball as a toddler and going on to play Division I ball at Drexel University before three ACL tears ended dreams of joining the WNBA. Raised in Philadelphia, Crane now lives in San Diego with a wife and toddler son and is the author of stories, essays, poetry and a debut speculative novel, which came out this week: “I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself.”

The novel is set in a society in which prisons have been abolished, but those judged to have committed crimes — or violations of the moral order — are assigned a permanent shadow. The “Shadesters” work as warnings to others, marking those they follow as second-class citizens. Crane’s focus is on Kris and her daughter, referred to as “The Kid,” whose mother — Kris’ wife — died while giving birth to her. The Kid leaves the delivery room with the same double shadow borne by her mother.

Crane, who uses they/them pronouns, spoke to The Times in late December about the origins of the book. A proponent of prison abolition, the author couldn’t help diving into its potential aftermath under a system that might never shake the impulse to punish and banish. “I wanted to see how our oppressive government can find a way to screw up everything, even something good,” Crane said. Equally central to the novel is an exploration of how grief changes people — the way it can become a personal apocalypse, irrevocably separating “before and after.”

Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Having tackled opioids in “Ohio,” Stephen Markley swings for the fences on climate disaster in his follow-up — which might have made better nonfiction.

Your book takes place in a dystopic future in which a young woman is grieving the loss of her wife. Is there a connection between dystopia and grief?

I’m interested in grief, and I just hate the “five stages of grief” and all those sort of things [that] shame people if they don’t feel like they’re moving through these predictable stages. Which is why fragmenting my novel was really a helpful way to bring out grief. Because for me, grief feels really fragmented. The memories come back in these short, weird snippets, you know? Your life is happening in the present tense, but then you have this quick reminder of this person. Over the years, those memories fade, and that’s another form of grief for me. Grieving the loss of the memories of these people.

It sounds like grief is something you’re intimately familiar with.

A close friend from college died suddenly in 2014, and it was very traumatic. He was one of my people. Just this special type of connection that transcends labels like friendship and romance. His loss doesn’t get any easier over time — if anything, my grief deepens and complicates. The forgetting, it really gets to me. It makes me cling and cling to what I do remember, to the person I loved, whose presence I can still feel everywhere.

This is one of the few books I’ve seen in which a character brings a child into a dystopia. Was there something specific you wanted to say about being a child coming up in such a world?

A lot of it came from my own fears and anxiety. We had just started talking about family planning when I started drafting this book. My wife had wanted kids forever, and she is seven years older than me. I was all on board, but I was so terrified of all of these unknown things. I had all these questions that were haunting me. I selfishly started writing into this idea, as a worst-case scenario, because I didn’t want to raise a kid alone.

‘Something New Under the Sun,’ Alexandra Kleeman’s astounding second novel, features a child star, an eco-cult and a sinister substance called WAT-R.

Why did you feel that this future world was the best setting for what is ultimately a personal story?

I think making it a different world creates enough distance for the reader to be able to see that comparison to our world without shoving it down their throat. It ended up becoming this dystopian book because I had the shadow idea baking for a really long time, before I had the plot of Kris and the Kid.

I wrote this weird little poem around 2013. It was meant to shame myself. I had a lot of shame about ways I behaved and people I’d hurt. And the poem asked, “If all the shadows of everyone you’ve ever hurt followed you around all day every day, would you still be so reckless with people’s hearts?”

These shadows remind me of Hawthorne’s “The Minister’s Black Veil” or “The Scarlet Letter.”

I did have “The Scarlet Letter” in mind. I haven’t read it since I was a kid, but I’ve always been fascinated by these physical markers that were meant to disenfranchise [Hester] and keep her isolated. So I had this in mind when thinking about the function of the shadows.

How did you come to imagine a society that manages to abolish prisons only to torment the “guilty” with shadows?

I didn’t originally envision the shadow premise as an alternative to incarceration. Mostly because the idea was very self-directed at first. I thought if I could imagine all these hurt people following me around, then I would 1) have to face myself and the pain I’d caused and 2) change for the better.

Then, years later, when I made the connection between the first line and this premise, I did quickly replace prisons with the shadow idea simply in order for the story to work and for the stakes to make sense. As the story developed and I went through revisions, I started thinking about [the novel’s President] as almost weaponizing abolition. He planted the seed of resentment toward incarcerated people getting “luxuries,” but in the same breath, he could also claim that he set everyone “free.” The book, in part, became an exploration of what it means to be free — and to whom these freedoms apply.

“Little Fires Everywhere” author Celeste Ng joins the L.A. Times Book Club Dec. 8 to discuss her latest bestseller, “Our Missing Hearts.”

In “A Christmas Carol,” Scrooge asks the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come if these things might come to pass. Did you feel you were writing into a possible future?

[Laughs.] There’s no prisons in my book, and that’s something I want to see in real life. Here’s prison abolition but in the worst way possible. But these changes are happening. Abolitionist organizers are doing so many incredible things. They’re getting prisons closed, they’re getting innocent people released. All these things that are small steps towards ultimate abolition. They are coming up with all these cool creative solutions and small ways to get there. I really do have hope for the future.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.