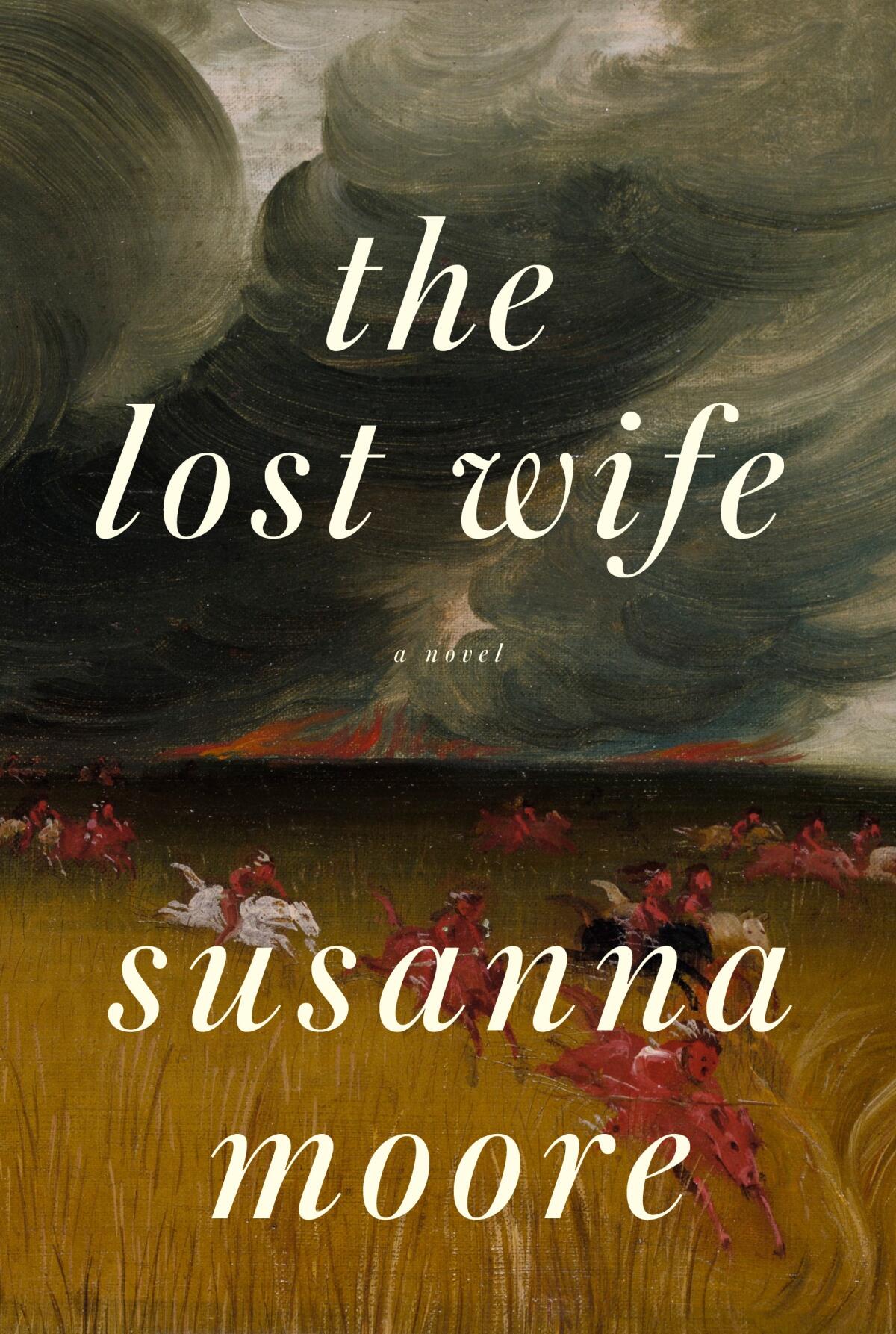

A woman is (not unhappily) kidnapped by the Sioux in Susanna Moore’s new novel

- Share via

Review

The Lost Wife

By Susanna Moore

Knopf: 192 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In Susanna Moore’s 1995 novel, “In the Cut,” Frannie Avery is looking for a bathroom in the basement of a dive bar when she stumbles on a man and woman engaged in a sex act. Even though she isn’t wearing her glasses, she manages to see that the woman is a redhead and has painted nails, and that the man has a tattoo of a spade on the inside of his wrist. Later the redheaded woman turns up dead, and a cop comes to ask her if she’s noticed anything suspicious in the neighborhood. He too has that spade tattoo.

Frannie notices all this because Frannie is a writer; in fact she teaches creative writing. Moore is also a writer and a teacher. The author of seven novels, Moore graces us with another one this spring, “The Lost Wife,” a welcome new display of her masterful approach to the undercurrent of violence that she believes runs beneath all human behavior.

The novel is based on the true story of Sarah F. Wakefield, who was abducted by Mdewakanton warriors during the Sioux Uprising of 1862. Wakefield too was a writer. She published an account of her ordeal in 1864 under the title “Six Weeks in the Sioux Teepees: A Narrative of Indian Captivity.” Wakefield, Frannie and Moore — all writers, and also all women. They all notice things that men do not.

Victor LaValle’s novel ‘Lone Women’ reinvents the western, adding horror and a Black woman pioneer protagonist — with help from the women in his own life.

“In the Cut,” Moore’s most acclaimed novel, which spawned a movie adaptation that may or may not have destroyed Meg Ryan’s career, depending on who’s asking, is a kind of noir. It takes place in a New York City more dangerous than today’s, and nearly every single male person appears as a possible threat. Frannie notices the holster on Det. Malloy’s ankle. She notices the way his pants fit. She notices the way men look at her at the bar. Walking up Broadway, she notices the slightest sound behind her.

“The Lost Wife” is its own kind of crime story. Fleeing an abusive husband, Sarah abandons her young daughter and makes a new life in Minnesota. In the West, she has no name. She needs no past. She finds a husband and settles in. But she is always looking over her shoulder. She notices her husband’s laudanum addiction. She notices the brewing unrest among the Sioux, who expect their annuity payment on their land.

One might call this hypervigilance “the female gaze.” It is the clear result of trauma — a decidedly female trait, but one that is learned. That is, until Sarah meets the Sioux.

Moore is a master of smallness. Her deceptively simple sentences are like geysers. The churning energy underneath is violent, animal and sexual. Her acrobatics in this novel reminded me of a scene from the 1992 film “The Last of the Mohicans” that takes place on the edge of a cliff, in which choices and motivations are conveyed only with looks and gestures — no dialogue. This is how we read the sexual energy in “The Lost Wife.” It doesn’t surprise me that Moore would be moved to write this book once she’d heard the story. Of the violent uprising, Sarah reflects: “It all seemed very orderly and reasonable, the way events in dreams seem to make sense.”

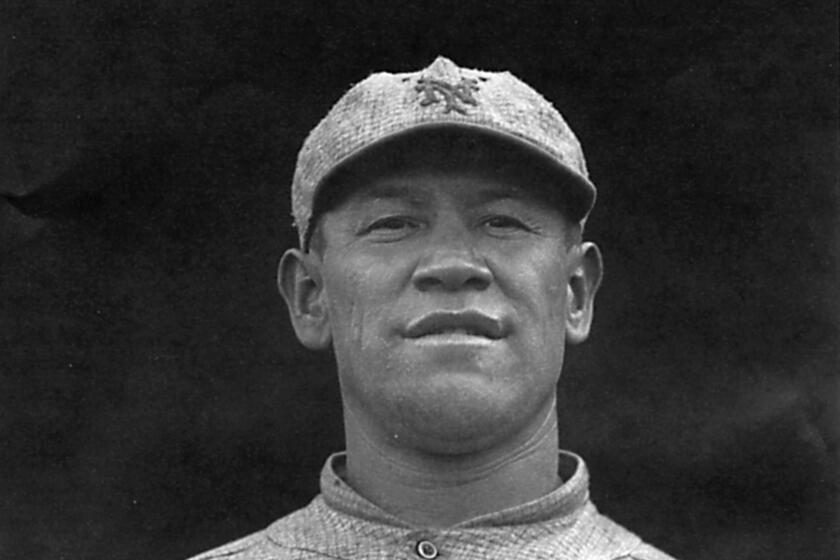

Jim Thorpe won two golds at the 1912 Olympics, then had them stripped (and posthumously restored this year). David Maraniss’ new biography honors him.

Wakefield claimed the only reason she and her children had survived was because of a Native man named Chaska. He bears the same name in Moore’s book. For Sarah, he is her “good Indian.” He tells her the Sioux want to kill her and her children, so he claims her as his wife to protect her. Read how he is described. Not a single other character in the book receives such attention:

“I had not seen him in two years, but I remembered him very well. He had a small scar, perhaps an inch and a half long, running from the right side of his mouth toward his ear. It was hard not to notice it, especially as it seemed to change color in different light. He was a favorite among the white women because of his quiet nature and because of a certain innocent beauty ... He was no longer the slender boy who milked cows for white ladies, but thicker and stronger. More solemn, with a certain disdainful gravity, as if someone or something had let him down along the way.”

When their wagon falls into a ditch, throwing Sarah and her two children into a muddy river, Chaska jumps to pull them out. Sarah tells him this is the first time she has seen him smile. “You haven’t been looking,” he says, “wiping the child’s face.” Finally, Sarah has met a man who is also paying attention.

Unfortunately, as you might imagine, it does not end well for Sarah and Chaska. I will leave the sad ending for readers. Sarah finds she must protect herself not from vengeful Natives but from white soldiers, who are perplexed at her defending the Natives who kidnapped her and her children. “Soldiers gather throughout the day to watch us, asking to see the white woman who married the Indian. Now and then one of them will shout at me, ‘What did he do to you, lady?’ and the others laugh.”

Last month’s James Welch Native Lit Festival brought together Indigenous writers Louise Erdrich, Sterling HolyWhiteMountain, Tommy Orange and more.

The year is 1862, and there is another war on, of course. Sarah’s husband is eager to get to the battlefield. Before they part ways, while taking stock of all their belongings that were destroyed during the uprising, he reminds her that many other white women captives were not “as obliging.” “They refused to dress in buckskin and moccasins and braid their hair, and did not converse happily with their captors in Dakota, yet they are now at home with their loving families, untainted by shame and dishonor.”

“‘But perhaps you liked it,’ he said.” At the end of Moore’s subtle reworking of Wakefield’s story, it’s obvious that Sarah’s husband has settled back into the groove of a divided world. For Sarah, her new life is just beginning.

Ferri is the owner of Womb House Books and the author, most recently, of “Silent Cities San Francisco.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.