Keanu Reeves returns for ‘John Wick: Chapter 4’

- Share via

Hello! I’m Mark Olsen. Welcome to another edition of your regular field guide to a world of Only Good Movies.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

‘Pixelvision’ revival. On March 28, the Mezzanine screening series will have filmmaker Michael Almereyda on hand to present 1992’s “Another Girl, Another Planet” and 1997’s “The Rocking-Horse Winner.” Both films were shot using the Fisher-Price PXL2000 video camera, meant to be an inexpensive camera for children that instead became a favored tool for alternative artists fond of its murky, textured images. Almereyda was among the greatest explorers of the aesthetic possibilities of the camera, also known as “Pixelvision,” so this evening should be a real delight, a rare chance to screen these works in a theater.

Investigating the ‘Erotic 90s.’ Following the “Erotic 80s,” the new season of Karina Longworth’s Hollywood history podcast, “You Must Remember This,” will explore the “Erotic 90s” with what promises to be a blockbuster 21-episode series exploring the intersections of moviemaking, sex and the culture-at-large throughout the decade. To go along with the podcast, the American Cinematheque will show featured titles through the end of May. Alongside films such as Paul Verhoeven’s “Basic Instinct” and Barbet Schroeder’s “Single White Female” will be relative rarities such as Sondra Locke’s “Impulse,” Ken Russell’s “Whore,” Louis Malle’s “Damage” and Uli Edel’s “Body of Evidence.” The podcast season launches March 28, and the film series begins that same day with a 35-millimeter screening of Philip Kaufman’s 1990 “Henry & June,” the first film released with an NC-17 rating.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

‘John Wick: Chapter 4’

Directed by Chad Stahelski, “John Wick: Chapter 4” again stars Keanu Reeves as an assassin who wants to find his way out of the business, but has to contend with the byzantine protocols of the High Table, the ruling body of an international crime syndicate. This time, John Wick finds his way from New York to the Moroccan desert, Osaka and Paris in a wild series of shootouts, fistfights and car chases. With returning cast members Lance Reddick, Ian McShane and Laurence Fishburne, this film introduces characters played by Donnie Yen, Bill Skarsgård, Shamier Anderson, Rina Sawayama and Hiroyuki Sanada. The film is in theaters now.

For The Times, Justin Chang wrote, “The meticulous foreshadowing of future conflicts feels appropriate to a world built, destroyed and rebuilt by endless cycles of killing; conveniently enough, it also lays the groundwork for future ‘John Wick’ spinoffs. If any do materialize, I hope they’ll be as lustrous-looking as this one, though also a bit more disciplined. There are moments when the pummeling virtuosity of ‘Chapter 4’ sputters and stalls, when its entrancing beauty takes an unproductive, ponderous turn. … Through it all, Reeves somehow barrels through the picture with equal parts rampaging force and Zen-like cool. Never one to upstage his fellow actors, he succeeds, as few movie stars could, at both drawing and deflecting the camera’s attention. Wick’s gun-fu is peerless, his endurance herculean, his weariness palpable.”

Jen Yamato profiled Stahelski, who went from being Reeves’ stunt double to what she describes as “the Bob Fosse of action cinema” for his delirious, dancelike construction of kinetic sequences.

Yet Stahelski is reluctant to describe himself as an artist, preferring to see himself as a craftsman at work. As Reeves put it, “Inside the craft is a philosophy, an existentialism. You can talk about it, or you can have a wide shot of a guy staring out into space with a tree next to him, in nature. Every color, every suit, his relationship with [cinematographer] Dan Laustsen, it’s all personal. I can’t unpack or take apart the tapestry and pick a thread. All of the threads lead to Chad.”

For the New York Times, Manohla Dargis wrote, “The constraints of Wick World put it safely on the side of full-blown fantasy, giving the series the feel of a grim fairy tale. It might seem like a distorted mirror of our world, but what’s notable are all the ways it’s different from ours — not just in its depiction of power but also of violence, which, for all the arterial spray, is as untethered from reality as it is in zombie flicks. … There is simply and once again Reeves, the axis who centers this franchise with his grave sincerity, beatific glow and mesmerizing, rooted fighting style, with its heavy-footed solidity and surprising suppleness. No matter what happens, nothing ever feels as poignantly at stake here as Reeves’s own ravaged, beautiful, aging body.”

For Vulture, Angelica Jade Bastién wrote, “Reeves has always been a performer defined not just by the delicate beauty of his body but an emotional clarity and sweetness that is almost nowhere to be found in this film. … What ends up most intriguing about his performance is the subtext of the movie’s denouement: the idea that Reeves is, for however long, ceding the ‘John Wick’ spotlight — unlike his aging-star cohort (think Brad Pitt in ‘Bullet Train’ and Tom Cruise in ‘Top Gun: Maverick’), who welcome neophytes into their fold but insist on outlasting them. Reeves is a star who doesn’t suck up all of the oxygen. He’s able to mold himself to the work and pull back when necessary — but maybe too far back this time, as his performance tips into laconic and guarded by the close.”

For the New Yorker, Richard Brody wrote, “The new film … has many of the same problems as its predecessors; although these problems are interesting, they’re far more fun to contemplate in the rearview mirror of thought than in the real-time forward motion of viewing. But something happens, fairly late in the game, that converts the film’s merely technical displays of bloody murder into something suspenseful and romantic, if no less silly. The details are too good to give away, but there’s no harm and much pleasure in considering how the movie climbs, slowly but surely, to that light-headed summit.”

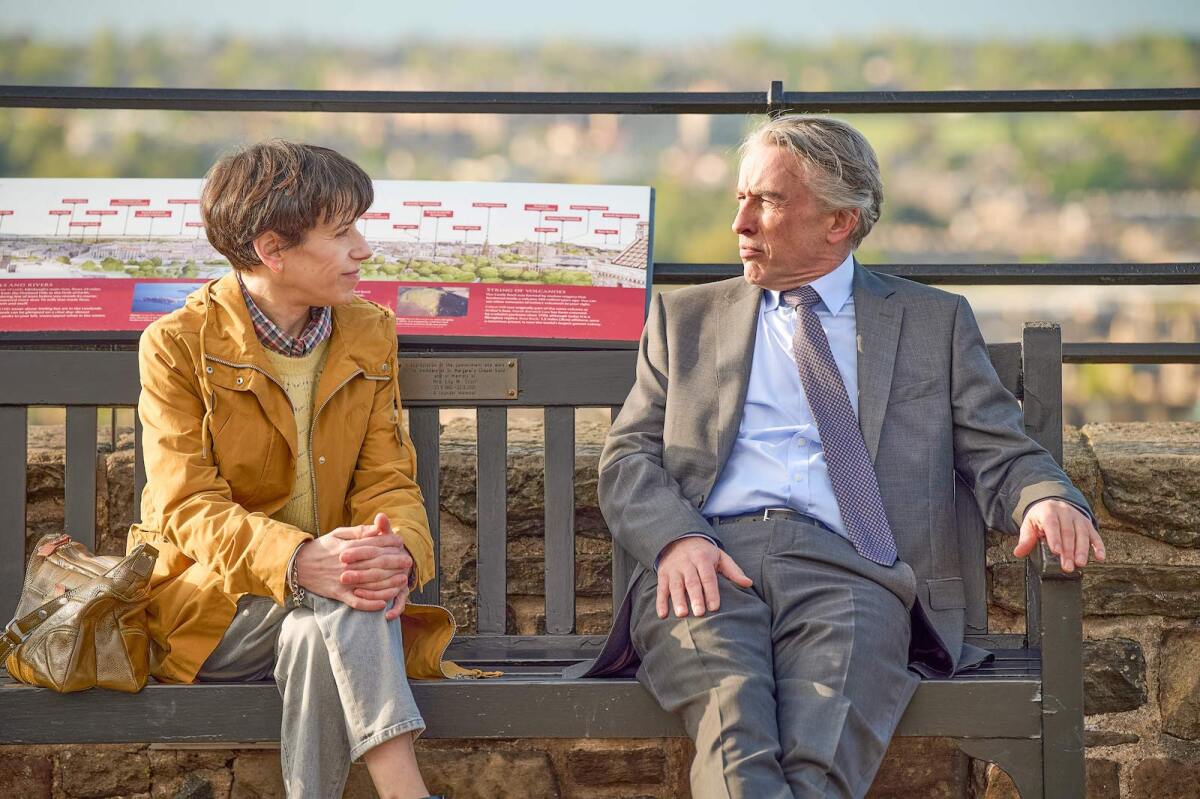

‘The Lost King’

Directed by Stephen Frears from a screenplay by Steve Coogan and Jeff Pope, “The Lost King” reunites the core creative team behind the Oscar-nominated “Philomena.” Based on a true story, the new film stars Sally Hawkins as Philippa Langley, an Englishwoman who becomes interested in Richard III and sets out to discover his long-lost remains. The movie is in theaters now.

For Tribune News Service, Katie Walsh wrote, “Toward the end, ‘The Lost King’ reveals a distinctly British obsession with royalty and propriety that doesn’t always translate with the same reverence abroad. But the more important story being told is the one about discrimination and misinformation; that fact can be twisted into fiction that’s perpetrated for centuries. Philippa’s mission to ensure Richard III’s royal coat of arms on his tomb might seem a bit superfluous, but for her, it’s about restoring the truth, not necessarily the title.”

Emily Zemler spoke to Frears, Pope, Coogan and the real Philippa Langley for a story about Langley’s struggles in being recognized for her discovery.

“I come from Leicester, so to me it was always comic,” Frears says. “It was always ridiculous that a king’s body should be found under a car park in Leicester. I’ve spent a lot of my life being told by women that they’re marginalized. And here was a story about a woman who had been marginalized and [we were] moving her into the center.”

For the Washington Post, Ann Hornaday wrote, “Ultimately, ‘The Lost King’ centers on Plantagenet-worthy politics, when the bigwigs at the University of Leicester try to elbow Philippa out of her due credit for finding Richard’s remains. (Unsurprisingly, that fight was rekindled with the U.K. release of the film.) With Hawkins’s alternately elfin and flinty performance at its center, ‘The Lost King’ winds up being a paean to amateurism and unconventionality. Greatness comes in all shapes, sizes and packages; genius can take any number of forms. Hidden depths are everywhere. You just have to know where to look, and do a little digging.”

For the Hollywood Reporter, Leslie Felperin wrote, “The result is pleasant-enough middlebrow entertainment that will serve the cinematic needs of older viewers especially. But it’s considerably less interesting than ‘Philomena,’ a more muckraking work that churned over the Catholic Church’s shameful past and had the all-powerful empathy-extracting weapon that is Judi Dench doing an Irish accent. Moreover, it’s just not as easy to get worked up about whether protagonist Langley will receive the due credit she deserves for her historical detective work, the plotline that dominates the latter half of the film along with whether or not her ex-husband John (played by Coogan) will get a nice new car.”

‘Tori and Lokita’

Written and directed by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, “Tori and Lokita” received a special 75th anniversary prize when it premiered at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival. The film follows two young African immigrants, Tori (Pablo Schils) and Lokita (Joely Mbundu), as they try to make a life for themselves in a small Belgian city, falling in with a ring of petty criminals. The film is in theaters now.

The Dardennes will be making a few appearances around town over the next few days, including a Q&A with a screening of “Tori and Lokita” on Monday.

For The Times, Justin Chang called the film “Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne’s strongest work in nearly a decade,” before adding, “The unremitting bleakness of their ordeal feels shockingly blunt even coming from the Dardennes, who, despite their rejection of sentimentality and uplift, have always maintained a sincere belief in the possibility of redemption. … But I think that the filmmakers’ pessimism is inseparable from their compassion and that their compassion is inseparable from their rage. That rage has many targets, some of which hover over this story in the abstract — the migrant crisis, anti-Black racism, crime and poverty, bureaucratic intransigence, the innate tendency of systems and individuals to prey on the young and vulnerable in their midst — and none of which are limited to the Belgian towns and cities where these filmmakers make their remarkable discoveries. The Dardennes are too honest to conceal their despair at the state of the world. They also know that the voicing of that despair can be its own small expression of hope.”

For the New York Times, Manohla Dargis wrote, “Time and again in the Dardennes’ movies, imperiled and isolated characters are saved — by themselves, by others — in moments that express the filmmakers’ humanism. It’s easy to imagine or, really, hope that something similar will happen in ‘Tori and Lokita,’ a possibility that starts to seem more and more like magical thinking, particularly given how abjectly African migrants are often treated. Surely, you think, someone decent will step up to offer help. What I didn’t grasp when I first watched the movie is that the act of grace I was anxiously waiting for had happened before the movie began. Lokita had once saved Tori; they saved each other. Yet in a world as barbaric as this one, who else is willing to step up?”

For IndieWire, David Ehrlich wrote, “The Dardenne brothers may not be known for mincing words, but ‘Tori and Lokita’ pioneers never-before-seen degrees of words un-minced. … Never before have these implicitly political filmmakers so nakedly allowed a moral parable to burn into the stuff of mad-hot polemic, but it’s easy to appreciate why the Dardennes might want to eschew what little subtlety they have left as they move into the twilight of their shared career (itself a testament to the strength that siblings can provide each other). Fringed with an even greater degree of futility than any of the duo’s previous work, ‘Tori and Lokita’ doesn’t harbor any delusions that shining a harsh light on such awful stories will ever be enough to make the world a better place, and yet — in the least uncertain terms imaginable — it leaves us with an indelible glimpse into the darkness that surrounds them.”

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.