Review: ‘Ray & Liz’ is a bleak, beautiful memoir of an unhappy English childhood

- Share via

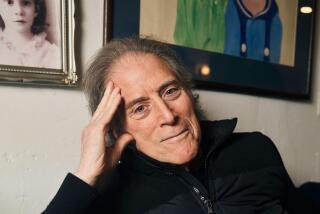

“My father, Raymond, is a chronic alcoholic. He doesn’t like going outside and mostly drinks homebrew.” The lines come from the back cover of “Ray’s a Laugh,” a celebrated 1996 book of family photographs by the Turner Prize-nominated visual artist Richard Billingham. They are elaborated upon with vivid spareness in the opening scenes of “Ray & Liz,” a haunting, fragmentary cinematic memoir that marks Billingham’s feature writing and directing debut.

For several minutes, the camera watches as Ray (Patrick Romer) stirs from his sleep, lights a cigarette and finishes off a bottle of the aforementioned homebrew. He spends each day in this self-imposed isolation, drinking and drinking, miserable yet strangely content. Apart from the fruit flies swarming about his dingy one-room apartment, Ray’s only company is Sid (Richard Ashton), the neighbor who replenishes his booze daily, and his estranged wife, Liz (Deirdre Kelly), a walking scowl who stops by for irregular visits.

Given the drifty, shifty narrative perspective, you might describe “Ray & Liz” as something of an irregular visitor itself. Although the picture hails from a long tradition of British social realism, with faint echoes of Terence Davies, Ken Loach and Andrea Arnold, its odd, time-shuffling structure seems to arise from the phantoms of Billingham’s memory. The story consists of two extended flashbacks to his Thatcher-era childhood, in which we get a piercing sense of the squalor and poverty, emotional as well as economical, that defined his family life.

In a miserable Black Country council flat, all filthy surfaces and peeling wallpaper, we catch glimpses of a younger Ray (Justin Salinger) and Liz (Ella Smith), though neither one threatens to become a protagonist, much less a hero. Ray is inattentive and ineffectual. Liz isn’t much more of a parent, though she does feel far more present, with her quick temper and imposing, tattoo-covered frame. She sits and smokes and does jigsaw puzzles while horror movies blare from the TV set in the next room. Booze and cigarettes are plentiful; money, not so much.

The first story, set in the late 1970s, recounts a tense, darkly funny incident in which Ray and Liz go out with their older son, Richard (Jacob Tuton), leaving their toddler, Jason (Callum Slater), with a mentally challenged relative, Lol (Tony Way). For reasons that are unsurprising but never predictable, Lol turns out to be a singularly poor choice of babysitter. The second story picks up this chain of neglect several years later, when Jason is now a 10-year-old boy (a quietly wrenching Joshua Millard-Lloyd) who goes out to play with friends one night and doesn’t return home, leading to his eventual placement in foster care.

Billingham shoots his characters and their cramped confines through a boxy, almost square frame. (The 16-millimeter cinematography is by Daniel Landin; the spare, evocative production design, by Beck Rainford.) The narrow dimensions and the grungy texture of the image evoke not only the mood of the past but also the look of Billingham’s photographs, placing his two chosen art forms implicitly in conversation.

One obvious but telling difference is that in the movie, the young future artist himself is present as an onlooker. (Sam Plant plays Richard as a teenager.) In contrast with the photographs, what we are seeing is a construct, a skillful arrangement of details filtered through the imperfect haze of memory. And curiously, both flashbacks are centered not on Richard but rather on the plight of Jason, the family’s youngest and most vulnerable member. Neither son is anywhere to be seen or heard of when we return to Ray in his room decades later, cast off, though not entirely forgotten.

The film’s interlocking themes are imprisonment and abandonment. Despite the occasional shifts in time and location, we always seem to be trapped in the same dingy room, one that rarely feels lonelier than when it’s crowded with people. But what distinguishes “Ray & Liz” is its ability to find strange tonal nuances within that terrible sadness; bleak as it is, it’s remarkably devoid of bitterness or rancor, and even its most despairing passages are flecked with humor and hope. This is personal filmmaking with a diarist’s sense of detail and an artist’s generosity.

‘Ray & Liz’

Not rated

Running time: 1 hour, 48 minutes

Playing: Laemmle Royal, West Los Angeles

‘Ray & Liz’

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.