Time and space could never contain musician, artist and thinker Genesis P-Orridge

- Share via

Asked in October about living with Stage IV leukemia, artist and musician Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, who died Saturday at age 70, referred to an idea that writer Grant Morrison had offered when they once spoke.

“Living in the space-time continuum in an apparent human body is a bit like wearing a diving suit,” P-Orridge, best known as a musician who coined the term “industrial music” with the pioneering British industrial groups Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV, recalled to The Times.

“In order to experience time and space and sensations and physicality, you wear this body, but it breaks down because it’s such a brutal environment.”

But, the artist added: “It’s a wonderful place to visit.”

Born in Manchester, England, as Neil Andrew Megson, the influential thinker took full advantage of both the “diving suit” and their earthen visit by plumbing the deepest catacombs of the human condition. P-Orrdige’s death was confirmed in a statement by their daughters, Genesse and Caresse P-Orridge, that was shared on Facebook by Psychic TV’s manager, Ryan Martin.

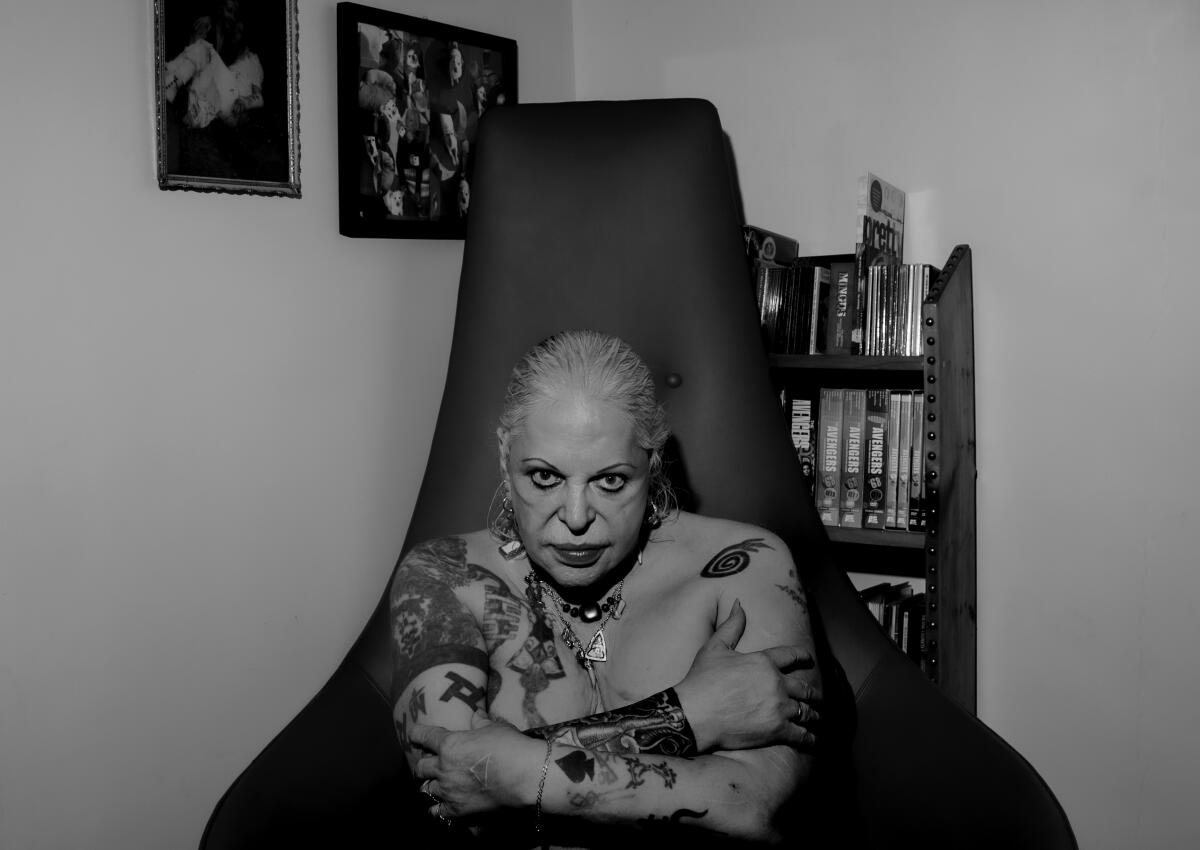

As a body-image advocate, P-Orridge helped define the so-called modern primitive tattoo and piercing movement of the 1980s, and they spoke of a pan-sexual, “pandrogynous,” future. An early proponent of gender-neutral they-their pronoun usage, Orridge was among the first artists to request that they be referred to as such.

Since the body will eventually break down anyway, they submitted, “surely the container should be as wonderful and amazing and imaginative as you can make it.”

Starting in the early 1970s, P-Orridge advanced a similarly provocative sonic philosophy that pure and electronically manipulated noise could be as expressive as musical instrumentation. Dubbing it “industrial music” in 1975, they and collaborator Cosey Fanni Tutti founded Throbbing Gristle in London with Chris Carter and Peter Christopherson.

The goal, P-Orridge once said, was “to play so loudly that sound waves could actually be seen” — and they once claimed to have succeeded. (But, then, P-Orridge also told of conjuring the ghost of late Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones during a seance, who then proceeded to play the main riff on the Psychic TV song “Godstar.”)

Issued by the group’s own Industrial Records imprint, Throbbing Gristle albums, including “The Second Annual Report of Throbbing Gristle” and the misleadingly titled “20 Jazz Funk Greats,” influenced a generation of synth-obsessing, static-harnessing artists including Nine Inch Nails, Aphex Twin and Ministry.

In a 1981 review of Throbbing Gristle’s first Los Angeles performance, The Times’ Richard Cromelin called its sound “a driving, relentless factory noise that assumed various rhythms as the set roared on.”

That may have been the case live, but Throbbing Gristle’s music was more nuanced and dynamic on record. “Hot on the Heels of Love” tapped synth-pop sounds that would inform the circuitry of bands such as Depeche Mode and the Human League. Other songs were darker and featured P-Orridge’s sinister, high-pitched wail.

Inspired by Beat generation writers Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs and their experiments with sound editing, the quartet set out to harness “the tools and the toys of the military industrial complex,” as P-Orridge told Popmatters. “We wanted to see what we could do to utilize relatively cheap or unique instruments and tools and gadgets, what we could do to play with them in such a way to subvert their original intention, which was control.”

Throbbing Gristle disbanded not long after that Los Angeles performance, with P-Orridge telling The Times during an interview at the time that its individual members would focus on a video-driven platform called Psychic Television.

That never materialized, but P-Orridge used the Psychic TV moniker for the rest of their life. With it, they made pounding acid house that predicted EDM and worked the rave-rock realm in the years before the 1989 British summer of love that propelled rave culture into the mainstream.

As they aged, P-Orridge used their platform to ponder the connection between body and mind and proselytize on the inevitable evolution of humanity’s collective “throbbing gristle.” A memorable conversationalist, they could speak for hours on dark magick and mysticism, the history of tattoo art and body manipulation and the ways in which pain and pleasure were intertwined.

As the subject, with their late wife and collaborator Lady Jaye, of the documentary “The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye,” the pair documented their attempts to transition into a bi-morphic pair of beings.

They told the Guardian in 2006, shortly before Lady Jaye’s death from stomach cancer, that such experiments were “inevitable if we’re going to evolve as a species. Our perception of the world is binary: right/wrong, black/white, male/female. We live in this miraculous technological environment, and yet our human behavior is still governed by basic impulses from prehistoric times.”

“It’s my body. And if I want to change it, that’s my right,” P-Orridge further explained to the The Times. “It’s just raw material. It’s not sacred. It doesn’t belong to a deity. It doesn’t belong to the government or any cabal of power brokers. It’s mine.”

In 2009, Throbbing Gristle reunited for a series of performances, including at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival. In a brief review, The Times noted that P-Orridge was “dressed as a Palm Springs mom possessed by a satanic shaman, lustily swinging a microphone between her legs.”

P-Orridge continued to incite, both with music and visual art, even after they were diagnosed with leukemia in 2017. Their most recent visual art show, called “Pandrogeny I and II,” opened at the Tom of Finland Foundation in Silver Lake in October. It featured sculpture, collage and photography that documented P-Orridge and Lady Jaye’s body alterations.

“To me, art has always been about evidence. Evidence of the lives of the people who are inspired by that divine spark that is so rare,” they said in advance of the show.

By then, the artist was connected to an oxygen tank and not expected to live much longer. They documented their body deterioration on Instagram. Asked about the prognosis, P-Orridge said, “It’s more a case of how long I’ll last, I think. I’m going to try and last just as long as I can.”

When it was noted that the artist seemed remarkably optimistic, they laughed and cited experiences they had working with Tibetans in Kathmandu and Nepal during a sabbatical from music. “You learn that what appears to be here, where we appear to be; what we think is real is just as likely to be an illusion. There’s no way of proving we exist.”

P-Orridge went on to describe time on Earth as “this incredible choice to explore whatever it is that being alive is — this incredible opportunity to explore your senses and your connections, and experience different places and different ways of thinking.

“There’s no end to learning more,” they concluded. “It’s this wonderful, wonderful experience. You can’t complain when it finally has to end.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.