Newsletter: Essential Arts: The art world was hot hot hot on NFTs. Is it just more of the same?

- Share via

Ladies and gentleman, the weekend. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, with the week’s essential culture news — and art historical dog paintings.

You down with NFT?

A single living artist. A major auction house. A sale that represented “a bold challenge to an entrenched system of representation by prominent art dealers.”

I’m not talking about last month’s auction at Christie’s, in which the artist known as Beeple (Mike Winkelmann) sold a digital collage linked to a nonfungible token for a brain-blasting $69.3 million. (Though I’ll get to that in a minute.) Go back, instead, to the fall of 2008, when Lehman Bros. was disintegrating, the Dow was in freefall and Young British Artist Damien Hirst was staging an epic auction of his work at Sotheby’s in London.

The sale, for a series titled “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever,” was unprecedented: A living artist, one who was well represented by a pair of major galleries — Gagosian in the U.S. and White Cube in England — was circumventing his dealers and taking 223 new works directly to auction. Among the objets up for bid was a sculpture of a golden calf presented in a tank of formaldehyde. (Because the art world was clearly concerned that the future screenwriter for “Velvet Buzzsaw” might not have enough material to work with.)

Hirst had couched the auction as landing a blow against an anti-democratic art world and its many gatekeepers. “It takes a bit of courage to get to the point where you just cut out the galleries and take a whole load of box-fresh pieces straight to market,” he said in advance of the sale. “No strings, highest bidder wins. Bang!”

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Never mind that it was precisely his gallerists who helped the auction house rake in a whopping $201 million on the two-part sale — and, in the process, likely helped keep the market for Hirst’s art afloat. Jay Jopling, the founder of White Cube, could be seen assiduously bidding on numerous lots.

As art critic Ben Lewis noted in a smart, well-reported story published in the Prospect shortly after the sale, “Jopling bid for 20 of the 56 lots on offer — an unprecedented intervention by an artist’s own dealer.”

Certainly, he could have been bidding on behalf of a client, Lewis noted, or he could have been simply buying up the work to keep Hirst’s prices stable. We’ll never know, since the auction house system has all the transparency of squid ink. What we do know is that Hirst’s high-end garage sale was touted as both the beginning and end of the art world.

“The reaction to the auction and its contents has run the gamut from doomsday end-of-civilization laments and serves-you-right righteousness directed at the art world ... to complete indifference, feigned or otherwise, on the part of many dealers,” wrote New York Times critic Roberta Smith in the wake of the sale.

“It’s amazing how many people behave as if, until quite recently, art and money have always been on opposite sides of some ethical bundling board.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about Hirst’s auction as the art world has ridden the NFT roller coaster over the last couple of months. (Don’t know how NFTs work? Start with this great explainer by my colleague Sam Dean. The short version: NFTs are digital certificates of authenticity recorded on a blockchain network that have the ability to verify the authenticity and ownership of a digital work.)

The Beeple auction generated a reaction that has all the echoes of the Hirst spectacle of 2008. Some bemoaned what it meant for art. (Beeple’s work is, to put it mildly, very bad.) Others argued that the sale would revolutionize art by making digital art more widely accepted and allow such artists to profit from their work.

This reaction was followed by a counter-reaction. Some wondered if the Christie’s sale wasn’t simply a publicity stunt to generate interest in cryptocurrency. Others scrambled aboard the NFT money wagon.

Actor John Cleese drew a picture of a bridge and then listed it on the OpenSea NFT platform. The New York Times sold an NFT for a column and donated the money to charity. Work by established digital artists such as Petra Cortright began to appear on platforms like Foundation. And even Hirst materialized like a blast from the past with his own NFT drop: a series called “The Currency Project,” which will consist of 10,000 oil paintings on paper. (Memo to Jopling: Stock up on cryptocurrency and a crate of Alka-Seltzer.)

Of course, the expected intellectual-property fights have begun. As my colleague Matt Pearce reported, artists who have long been allowed to sell ink-and-paper drawings of their comic book pages and covers have been warned off creating NFTs of their work with DC Comics and Marvel characters.

Currently, we have moved to the muckraking phase of the cycle, as reports emerge about NFT scammers; the fact that cryptocurrency is not only taking a toll on the environment but it can also be pretty useless; and the fact that NFT auctions don’t generate very much income for most working artists.

None of this should be entirely unfamiliar to the art world, a universe in which a handful of artists make piles of money while everyone else barely covers their rent, and where gallerists send art on epic journeys to fairs around the world, so that a private-plane-flying patron might encounter them inside an air-conditioned convention center. There’s something about a ginormous carbon footprint that gives a work of contemporary art a certain je ne sais quoi.

What has been enjoyable about the NFT ouroboros of hype is seeing some of the responses.

Sam Newell and Vince McKelvie, a couple of new media artists, created a website called Beeple Generator that cranks out downloadable images that riff on Beeple’s style of 3D digital illustration. Unlike Beeple, however, these are imbued with wry humor: say, a banana taped to a purple landscape (a nod to a work by Italian prankster Maurizio Cattelan), or a figure that bears a striking resemblance to Keanu Reeves holding a trio of dogs.

“We had to make a way for everyone to get in on the action,” Newell told me via DM.

Other more serious projects have also emerged, including a group show organized by the digitally minded art spaces Transfer and left.gallery. “Pieces of Me,” as the show is called, features works by 50 artists that serve as “an exhibition of offerings to the aggregate hype of the emerging global NFT marketplace.” All come with nonfungible tokens, natch.

While the show’s written materials wink at the hype, the works — by artists such as Lorna Mills, Claudia Hart and Julieta Gil — broach serious issues in compelling ways, including gender, sexuality, patriarchy and digital culture. Through left.gallery’s website, I found myself absorbed by an earlier work that was linked to blockchain: Brody Condon’s “Exorcism: Annaliese” a video that takes publicly available audio of children who are said to be possessed and uses it to create abstract digital renderings in 3D. I couldn’t stop watching.

But ultimately it’s the art I’m intrigued by, not the sales mechanism.

A decade after Hirst’s “historic” auction, Artnet’s Tim Schneider had a look at the value of the works he sold at Sotheby’s and found that many of the pieces had failed to hold their value. The sale was less a revolution than a highly aestheticized news conference. Artists never got rich by staging their own auctions; the art world’s gatekeepers (including auction houses) remain.

It’s an instructive lesson for the current moment.

Here’s hoping the guy who dropped $69 million on Beeple really enjoys the work. Because he’s probably going to be holding onto it ... for a very long time.

Civilization begins?

Cultural institutions are slowly returning from the long coronavirus-induced slumber. Museums are reopening to the public and performing arts organizations are publishing calendars of events. Events!!

Times art critic Christopher Knight cruised out to the Getty Villa to check out “Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins,” which seems like the perfectly titled exhibition for the moment. Originally scheduled to open last year, the show, which is drawn from the collections of the Louvre in Paris, is “a small but absorbing” examination of art produced along the Fertile Crescent, in an area centered in modern-day Iraq. The show, writes Knight, “represents the start of the city as a framework for social and cultural life.”

Live theater isn’t up and running yet, but a couple of alternative productions nonetheless take viewers to interesting places. Theater critic Charles McNulty reviews Robin Frohardt’s “Plastic Bag Store: The Film,” presented by CAP UCLA, and Elevator Repair Service‘s “Baldwin and Buckley at Cambridge (In Progress),” presented by REDCAT. The former is film that features puppets in an immersive environment; the latter, reimagines a famous debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr. that took place in 1965. Writes McNulty: “While we wait for live performance to return, let’s at least remind our palates of the taste of the unusual.”

Broadway in turmoil

Earlier this month, the Hollywood Reporter published a volcanic exposé about film and theater producer Scott Rudin that described epic physical and verbal abuse of staff, colleagues, directors and artists — including smashing an assistant’s hand with a computer and throwing objects during tantrums.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Rudin issued an apology in the wake of the report and announced he’d be stepping back from some projects. But, in an essay published last weekend, Charles McNulty asked if that was truly enough and noted that many Broadway luminaries had remained silent on the matter. One of the few who spoke up: Tony-nominated actress Karen Olivo, who issued a statement early on calling the lack of condemnation “unacceptable.”

The silence, McNulty writes, isn’t just about Rudin, but about a culture in theater that has historically tolerated abuse and humiliation. “Cruelty,” he writes, “isn’t the path to excellence.”

On Wednesday, Hugh Jackman, star of the upcoming Broadway revival of “The Music Man,” issued an all-caps statement in support of individuals who have spoken out about Rudin’s behavior and said that “Music Man” was “rebuilding” its team. “This has started a conversation that is long overdue, not just on Broadway,” Jackman stated. But even if, as Ashley Lee reports, Rudin is no longer a producer of Aaron Sorkin‘s staging of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” which “holds the record as the highest-grossing American play in Broadway history,” critics (among them, McNulty) note that Rudin is likely to nonetheless profit from his productions — even without an active role.

Vulture, in the meantime, rounds up the experiences of Rudin’s former assistants. It’s not pretty.

Museum time

MOCA lost a high-profile staffer when Mia Locks, senior curator and the head of new initiatives, resigned after less than two years on the job. In an exit email to staff, she said she was grateful that the museum had launched a diversity and inclusion initiative titled IDEA, but that “MOCA’s leadership is not yet ready to fully embrace [it].” Locks did not respond to a request for comment, but a spokesperson for the museum said that the institution is working to “fulfill our IDEA vision,” The Times’ Deborah Vankin reports.

Vankin has more museum dirt: the literal kind. It turns out that while the Getty Museum has been closed to the public, a bunch of moths have moved in and made themselves at home. “As if COVID-19 shutdowns and the financial fallout weren’t enough, a noticeable uptick in unwanted pests, including insects and rodents, afflicted museums globally during the pandemic,” she writes.

Oscars party on

It’s awards season! Which means the broadcast equivalent of Zoom meetings with gowns and trophies! Steven Soderbergh, who is directing the 93rd Academy Awards show with Stacey Sher and Jesse Collins, says that Sunday’s program will feel more like film than a TV awards ceremony. Though, as he told my colleague Josh Rottenberg, he is prepared for a critical pile-on: “You have to surrender to the fact you’re just going to be a human piñata.”

The Oscars will mark a big reveal for Union Station, which will serve as the site of the awards portion of the ceremony. The station wrapped up an eight-year, $4.1-million restoration last month that revealed bright, painted plaster ceilings under nearly a century’s worth of grime and shining 24-karat gold leaf filigree on bells that were thought to be solid cast iron. Deborah Vankin explores the many surprises and mysteries the restoration has uncovered.

Though I still think the awards shoulda been held at the Music Center. (C’mon Academy, it’s this thing called solidarity with the arts.)

In the meantime, I sat down and watched all of the best picture nominees — including “Sound of Metal,” “Nomadland,” “Minari” and “The Father” — and had a look at how they employed design and architecture to further their narratives: “In these films, the aspirational single family dwelling of the mid-20th century seems but a hazy dream. Instead, characters carve out their existence in the in-between spaces: vans, trailers, guest rooms and the ramshackle houses shared by activists fighting for a common cause.”

Need more? The Times’ Angie Orellana Hernandez rounds up all the Oscars essentials, including where to watch and who might win. You can find all of our coverage at latimes.com/oscars.

Essential happenings

Matt Cooper has the L.A. culture picks — 24 of them — including outdoor performances of “Trouble in Tahiti” by Pacific Opera Project and a screening of the concert film “Fandango at the Wall — the Shapeshifter Sessions” with Grammy-winning jazz musicians Arturo O’Farrill & the Afro Latino Jazz Orchestra plus a group of master son jarocho musicians. (That fandango looks like a pretty blazing jam. Catch the trailer here.)

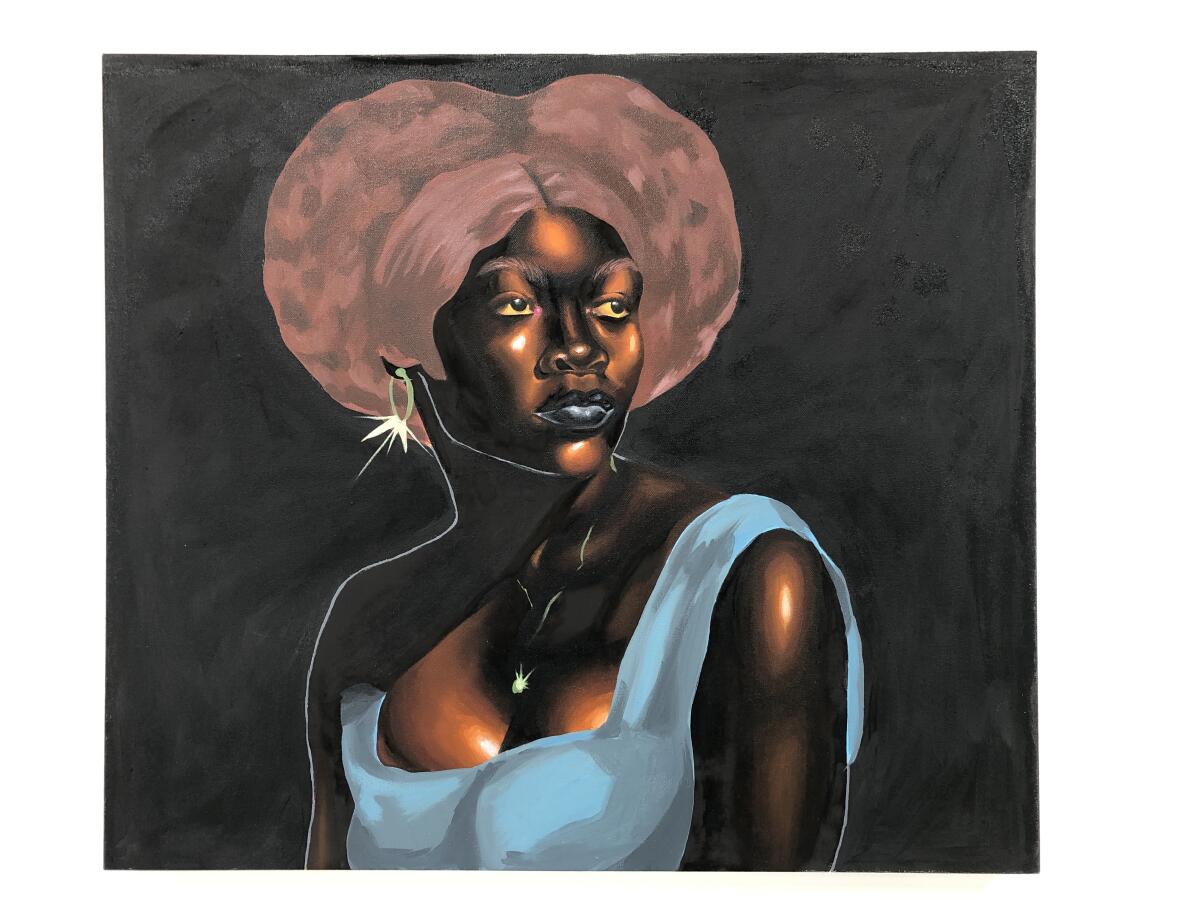

Absolutely worth checking out is “Shattered Glass” at Deitch in Hollywood, a group exhibition organized by Melahn Frierson and AJ Girard that features 40 international artists of color “whose subjects don’t ask, but rather demand to take up space.” With work by artists such as Lauren Halsey, rafa esparza, Jaime Muñoz, Gabriela Ruiz, Mr. Wash, Mario Ayala and Kandis Williams, it’s the rare major gallery exhibition that actually reflects Los Angeles.

The New York Times has a roundup of online dance, including a poignant performance by David Adrian Freeland Jr., of L.A. Dance Project, that was filmed onsite at Hauser & Wirth in downtown Los Angeles.

Passages

Artist Roderick Sykes, a co-founder of the Black art enclave St. Elmo Village, the residency and community space that nurtured generations of artists and the founders of the Black Lives Matter movement, is dead at 75. “We are an example to the community of what you can do when you don’t say, ‘I can’t,’” Sykes’ wife, Jacqueline Alexander-Sykes, told The Times’ Jessica Gelt.

Jay McCafferty, an L.A. conceptual artist known for employing light and magnifying glasses as an artistic tool, often creating burned, perforated surfaces on his work, has died at 73.

Allan Schoener, the curator who organized the controversial “Harlem on My Mind” at the Metropolitan Museum in 1969, an exhibition that became a flashpoint for not featuring art by African American artists, but whose legacy was reconsidered in the 1990s, is dead at 95.

In other news

— An interesting assignment for L.A. design schools would be to come up with a food cart prototype that is fully code compliant so food vendors don’t keep having their equipment confiscated by inspectors.

— Affordable housing is not only not very affordable, half a million affordable housing covenants are set to expire in the next eight years. Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal, a founder of the L.A. Tenants Union, gives the public-private partnerships that make affordable housing possible a good scouring.

— What we can learn from Santa Rosa‘s six-month experiment with a tent city for homeless people.

— Archeologists say they have found the vestiges of Harriet Tubman‘s lost Maryland home.

— The Smithsonian (along with many other museums) once collected the bones of the enslaved. Now they reckon with their proper burial or repatriation.

— The National Trust for Historic Preservation has launched a $1-million pilot program to help guide campus leaders at HBCUs in the preservation of their landscapes.

— This is a really insightful interview with Hammer curator Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi about how the “Made in L.A.” biennial not only came together, but how the works in the Huntington installation are in conversation with that institution’s complicated history.

— Aruna D’Souza has a great read on how Asian American artists have banded together to fight discrimination and anti-Asian violence through art and through activism.

— The story of the girl in the famous Kent State photo and the photographer who captured her grief.

— A new tapestry of the Virgin at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels by artist John Nava was inspired by a DACA recipient.

And last but not least ...

Some belated 4/20 content: the smoking dogs of art history.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.