SFMOMA acquires capsule from Tokyo’s demolished Nakagin Capsule Tower

- Share via

I’d rather be having tea at the Prada Caffè at Harrod’s in London. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, art and design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, and instead I’m in L.A., rounding up the week’s essential arts news:

A capsule, a concept

When demolition crews in Tokyo began to pry apart the Nakagin Capsule Tower last spring, it felt like the end to one of architecture’s more curious experiments. The tower, designed by architect Kisho Kurokawa and completed in 1972, was perhaps the most prominent example of the short-lived Metabolism movement of the 20th century, which sought to create buildings and megastructures that could be more organic or cellular in nature — structures that could expand, contract or mutate on demand.

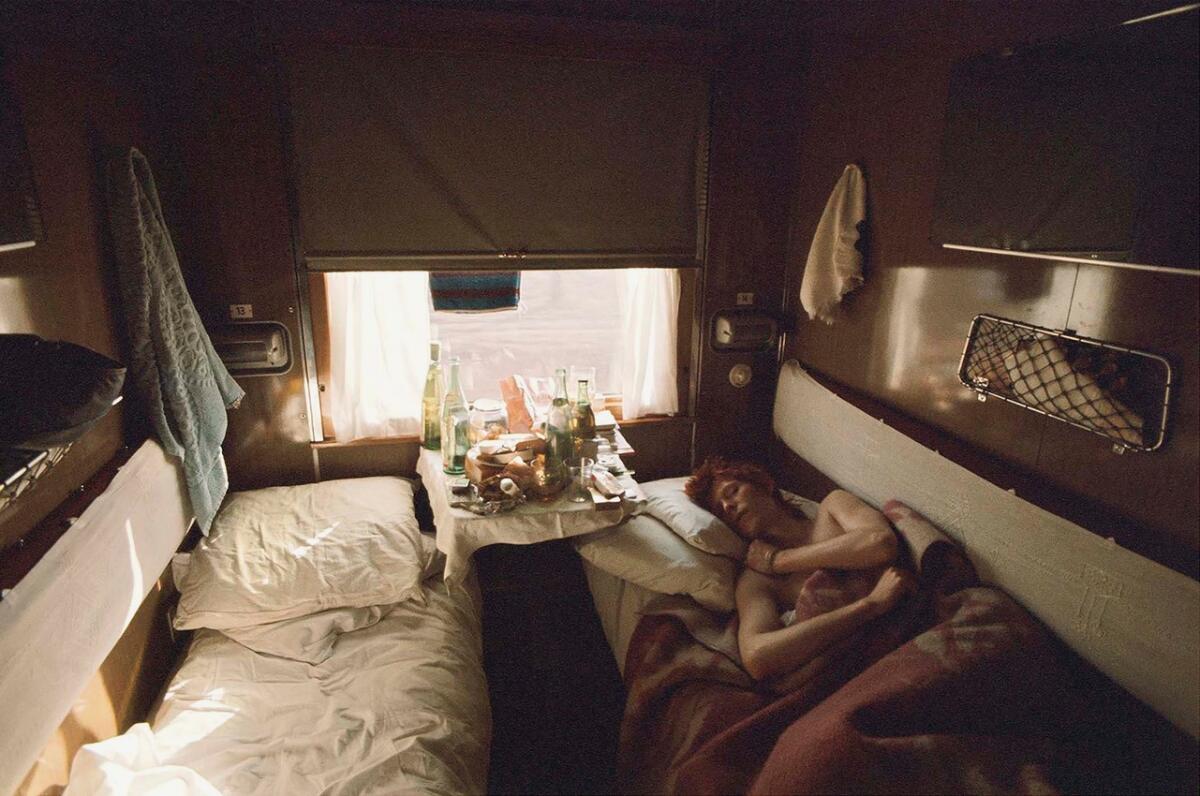

Nakagin consisted of two central 13-floor service cores, onto which 140 prefab pods were attached. (From the street, the building resembled a massive sci-fi honeycomb.) Each of these capsules sported a bed, a fold-out desk and a reel-to-reel tape player, and they were marketed toward businessmen who regularly overnighted in Tokyo. The idea was that capsules would be replaced and upgraded over the years — and that the owner of any given capsule could relocate it to other towers that might ultimately be built.

Time and neglect, however, intervened. And this quirky yet beloved tower was demolished last year. (For months, I watched the entire dismantling process on social media.)

Thankfully, the demolition isn’t the end of the story.

Preservationist Tatsuyuki Maeda, who led the Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Restoration Project, and for years fought valiantly to prevent the demolition, did manage to preserve 23 capsules. (A number of them were displayed outside of the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, also designed by Kurokawa, last May.)

Now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is set to announce that it has acquired Capsule A1302, which was owned by Kurokawa himself. (The architect died in 2007.) The capsule joins other important Japanese architectural holdings in the museum’s collection, including work by Fumihiko Maki, a fellow Metabolist whose firm designed the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, located right across the street from SFMOMA. The museum has also collected a series of photographs by Noritaka Minami that documented life inside the tower in the decade before its demolition.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, SFMOMA’s curator of architecture and design, says the capsule is a major score. “It’s so rare to collect a 1-to-1 scale piece of architecture,” she says. The pods’ size — only 104 square feet — makes their display in a museum feasible. “It can fit inside, outside and that’s phenomenal for us.”

More significantly, the capsule fits the museum’s broader collecting aims: architecture that leans into the conceptual and is “future-facing,” explains Dunlop Fletcher. “The Metabolists fit well with Lebbeus Woods and Archigram, which are also in the collection. ... But it’s generally hard to find material related to Metabolism on offer.”

Dunlop Fletcher had been intrigued by the building for some time. She traveled to Tokyo as the tower was coming down and gathered with Maeda and others who owned capsules within the building. “They were these interesting characters who each had a capsule and they rented an apartment across the street and they would get together every day to watch the building being dismantled. It was a range of emotions for them. And it was very special that they invited me to that space. ... It was an incredible experience.”

Through their efforts, Maeda and the others have helped keep the concepts that gave rise to the Capsule Tower alive. Kurokawa’s architecture connects with a host of contemporary concerns: tiny homes, sustainability and density. “Instead of tearing down a whole building, can you repair a piece of it?” asks Dunlop Fletcher. “How do we live more efficiently?”

“I like the nomadic idea, the challenge to land ownership,” she adds. “What if you just had your pod and you could plug it into this core or that core?”

The dismantling of the Nakagin Capsule Tower was painful to watch. (I have an inexplicable fondness for the building, which I toured in 2019.) But in some ways, it also marked an opportunity. One capsule is coming to San Francisco; others are likely to materialize in other locations around the world — spreading Kurokawa’s ideas in the process.

“It’s not just the physical form we need to hold on to,” says Dunlop Fletcher, “it’s the concept.”

SFMOMA completed the acquisition of the capsule late last month; an exhibition date has not yet been set.

On and off the stage

“A Transparent Musical,” the show inspired by Joey Soloway‘s TV series about a patriarch who comes out late in life as transgender, is having its world premiere at the Mark Taper Forum. Times theater critic Charles McNulty found the production lacking. “If someone had blindfolded me and brought me to this production, I would have assumed that I was watching a performance by a talented and extremely well-funded amateur troupe in residence at an LGBTQ+ community center.” And it goes on from there...

With the Tony Awards coming this Sunday, McNulty says it’s time to give a prize to a key constituency of live theater: the core audiences — who have endured COVID, inadequate bathroom facilities and concession-stand gouging to go see performers make magic onstage. “A special award to the stalwart Broadway theatergoer, without whom all of the year’s celebrated excellence would be as meaningless as the proverbial tree falling in a forest with no one around to hear it.”

In the galleries

At the Broad museum, Times art critic Christopher Knight reviews the show of Keith Haring‘s art — work made during the culture war of the ‘80s that connects to battles flaring today. Haring’s work, writes Knight, covers a wide range of themes, giving “prominence to pleasurable fun, like using loud Day-Glo paints that would interrupt the contemplative quiet of a typically hushed art gallery with the vivid exuberance found on a packed gay bar’s liberating dance floor. Others were sober — imagery linked to political repression, the perpetual threat of nuclear annihilation, apartheid cruelty, Reagan-era greed, culture war incited by hate from the religious right, apathy toward the exploding AIDS crisis and more.”

New York gallerist James Fuentes opened a space in Hollywood last month and the debut show features more than a dozen paintings by Philadelphia-based painter Didier William. I’ve been running into William’s work in group shows for a number of years and was excited to see this intriguing solo presentation. His canvases often feature faceless figures covered in eyes as well as graphic elements that draw from the spiritual traditions of his native Haiti. It’s in its final week, do not miss!

At the Wende Museum in Culver City, there’s a show of photographs by Geoff MacCormack of David Bowie‘s travels through the Cold War-era Soviet Union. The show captures a journey made by the artist after his tour of Japan in 1973, when he headed overland through the Soviet Union to Europe — a trip that included a week on the Trans-Siberian Express. “This exhibition is basically holiday snapshots,” guest curator Olya Sova tells The Times’ Deborah Vankin. “Not David Bowie in the studio, no makeup or posing with lights.”

Musical notes

Recent Pulitzer Prize-winner Rhiannon Giddens is music director of the Ojai Music Festival this year; she talks to contributor Tim Greiving about busting through genres in her work and in this year’s festival. “There is an element of uncertainty about a program like this,” she tells him, “which is the point. There will be years where everything has been written out, and every concert has all pieces programmed, and they’ve been practiced and everything. This is not that year. ... I think everybody will have moments of, like, ‘I’m not sure what’s going to happen right now.’ But I think that’s powerful.”

The Times’ Reed Johnson reported on the oldest attraction at the Hollywood Bowl: the annual Mariachi USA festival. An industry trope is that mariachi doesn’t sell records. But as Johnson shows, it has sustained a long-running L.A. tradition.

Design time

It’s 1971 and an aspiring movie director is trying to make it in the business. The business? Cheap grindhouse flicks that deliver a steady stream of nudity and gore. The aspiring director is an Iraqi Jew named Seymour, who, in addition to his all-consuming job in the lower rungs of Hollywood, is also contending with prickly marriage and a new infant. I review Sammy Harkham‘s new graphic novel, “Blood of the Virgin” — an intriguing story of ‘70s-era L.A.

The School of Architecture, which for decades was based at Taliesin outside of Phoenix, relocated to Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti, also in Arizona, during the pandemic. Metropolis’ Sam Lubell checked in to see how things are going. “With six semesters in the books (including a couple made very complicated by the pandemic),” he writes, “TSOA appears to be thriving in its new home.”

Essential happenings

My colleague Steven Vargas has his list of culture picks for the week, including the revival of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “A Soldier’s Play” at the Center Theatre Group.

Plus, Matt Cooper has all of the greater L.A. happenings for Pride month.

Moves

Tim Griffin has been named the executive director of the experimental opera company the Industry. A contributing editor at Artforum, he also recently served as executive director at the experimental New York art space the Kitchen.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Selene Preciado has been named the new curator and director of programs at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions. She joins the organization from the Getty Foundation, where she helped manage the Getty Marrow Undergraduate Internship Program and support the Pacific Standard Time initiative.

For the record:

10:47 a.m. June 12, 2023An earlier version of this article misspelled Selene Preciado’s first name as Selena.

Robert W. Lovelace, an executive with the Capital Group, has been named chair of the J. Paul Getty Trust.

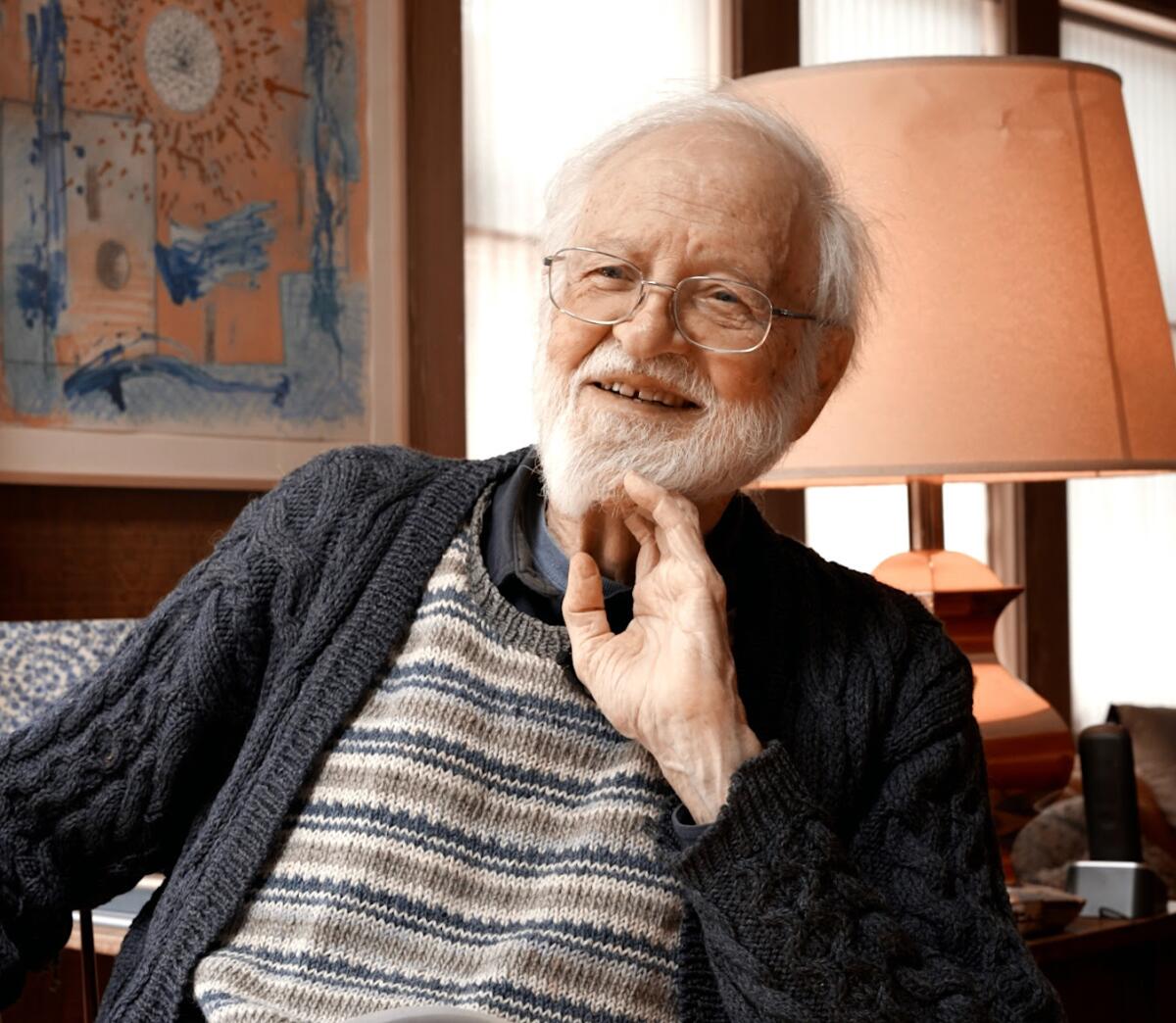

Passages

Artist Jim Melchert, who created elegant, conceptual work in a range of media and served as a beloved mentor to generations of students at UC Berkeley, has died at 92. Contributor Sharon Mizota pays tribute to her former teacher: “It was in Jim’s class that I first felt the inkling that there was more to being an artist than simply expressing yourself. It was also about paying attention — looking closely and curiously — and being open to where it might take you.”

Robin Wagner, a Broadway set designer who fabricated the stage environments of “A Chorus Line,” “Angels in America,” “Hair” and many more, has died at 89. Wagner, as contributor Barbara Isenberg writes in his obituary, never formally studied theater design. Instead, he once said, “I was taught by directors.”

In the news

— Several theatrical productions canceled shows in New York City due to the smoke conditions. Among them: Jodie Comer halted a matinee of Broadway’s “Prima Facie.”

— A number of arts institutions also closed temporarily due to wildfire smoke, including the Noguchi Museum and the outdoor Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens.

— A good time for climate protesters to harangue MoMA‘s board of directors.

— Architect Harry Gesner‘s Malibu ”Wave House” is on the market for $49.5 million.

— SFMOMA‘s facade is looking grungy.

— Amid sky-is-falling reports about San Francisco, Claudia La Rocco writes about a bloom of grassroots cultural happenings.

— Joan Acocella reviews Jennifer Homans’ very hefty biography of George Balanchine — so hefty that the review is broken up into two pieces.

— I really appreciate Ben Davis’ take on the Warhol/Goldsmith copyright case, which notes that the Warhol in question — well, it’s not very good.

— Alice Procter at Hyperallergic also has a terrific review of Hannah Gadsby’s “Pablo-matic” show at the Brooklyn Museum, which has been causing kerfuffles.

— The curious legacy of North Korean monuments in Africa.

— A stone sarcophagus from the 2nd to 3rd century Yayoi period was opened in southwestern Japan. What could possibly go wrong?

And last but not least ...

Crashing Henry Kissinger‘s 100th birthday.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.