Chicano Park 50 years later: Coronavirus delays celebration but historic moment still matters

- Share via

A college student watched as construction crews and machinery descended on a parched piece of land beneath the enormous highway pillars of a freeway intersection in Barrio Logan, or Logan Heights, the historical heart of the Mexican American community in San Diego. The workers had been sent to lay down a parking lot for a future substation of the California Highway Patrol.

But the neighborhood had already suffered a double bifurcation, first, by the construction of the 5 Freeway and then by the completion of the swooping Coronado Bridge in 1969. An estimated 5,000 homes or businesses had been razed or destroyed. Barrio Logan, cut in half, then halved again, was now riddled with junkyards.

For the student, Mario Solis, the sight of construction machinery hit like a cruel insult. The community had long been promised a park, not a CHP station. He headed straight to the classroom of a Chicano studies course at San Diego City College and sounded the alarm. Word spread and on that day, April 22, 1970, locals collectively descended onto the land under the intersection, raised a flag and instituted their own park — Chicano Park — without permission.

“The next step was really fast — everything started going just like that,” recalls Logan Heights native Josie Talamantez, snapping her fingers, in the 1988 documentary “Chicano Park” by Red Bird Films. She was in the classroom when Solis — later dubbed “the Paul Revere of Chicano Park” — just burst in. “We came down, came into the park, we made human chains around the tractors.”

The students and community members occupied the site for 12 days, clearing the ground and planting flowers and nopales until the city agreed to buy the land from the state and build a park.

Fifty years later, the incident remains one of the most impactful yet frequently overlooked episodes in the history of social struggles in Southern California, the state and perhaps nationally.

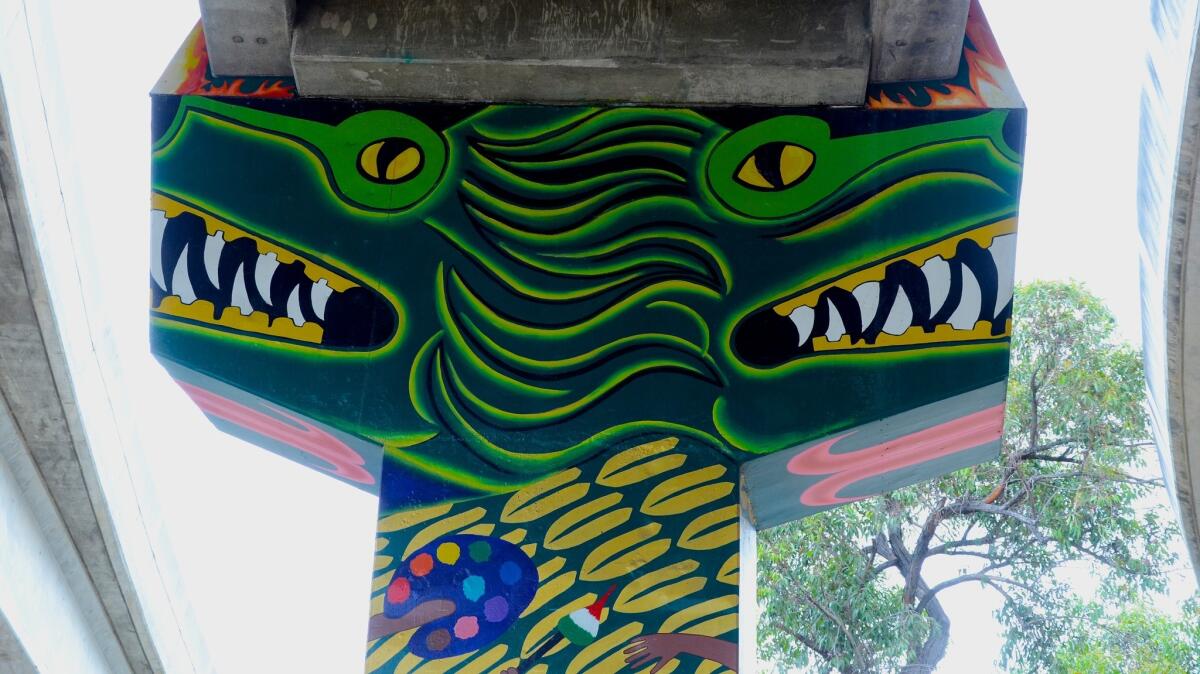

Chicano Park became a locus for mural artists, part of the renaissance of Chicano and resistance murals of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. Soon, all the freeway pillars were adorned with artwork that traced the history of the local people to Baja California and Mexico’s northern states, and deeper, to the founding of the Aztec Empire, reflecting the cultural flurry that accompanied the ethnic nationalism movements of the period.

“It was literally a left-over space, a throwaway space, and the community took it,” said Alexandro Gradilla, associate professor of Chicana/o studies at Cal State Fullerton and a San Diego native. And now, “The community has literally fused with that space.”

On Saturday, Mexican Americans from across the U.S. Southwest were expected to descend upon Chicano Park once more for the annual Chicano Park Day. This year’s 50th observance was going to be the biggest ever, drawing bands, vendors, dance troupes and lowrider vehicles, as well as the scents of BBQ wafting from the neighborhood streets.

But the coronavirus pandemic has halted the anniversary celebration.

The festival will be postponed, according to a statement by the Chicano Park Steering Committee, although a new date has not yet been set.

The temporary cancellation has been a gut punch to the dedicated adherents of old-school Chicano culture who gather there: the fist-raising Brown Berets, the danzantes, the cholos, the lowriders, the veteranos and veteranas who rep that distinct barrio style of Pendleton shirts, derby hats, classic tattoos and a smooth dose of attitude.

“Chicano Park reminds us that if we gather together and we fight for something, it is possible for us to win,” said artist Soni López-Chávez of the local La Bodega Gallery. “Everyone was super excited to celebrate, and for us to not be able to gather as one is really sad. It’s crushing.”

The San Diego tradition, held on the weekend nearest to April 22, had increasingly drawn visitors from L.A., Orange County and the Inland Empire. For now, artists and surviving activists from the era are still finding creative ways to honor the heritage of Chicano Park on its golden anniversary.

The Steering Committee all week organized live online screenings and history sessions. On Wednesday, the anniversary of the founding, surviving members of the original band and their descendants gathered, wearing masks and adhering to social distancing guidelines, to re-raise their founding flag.

“I can feel them here, people who were here with us for the takeover of this land, for Chicano Park,” said Tomasa “Tommie” Camarillo, the committee chair, in a video of Wednesday’s flag-raising. “I know they’re watching us with these big ole smiles, saying, ‘See? I knew you guys wouldn’t give up, you guys would stay there and finish what we started.’ And hopefully every generation will be the same.”

Chicano Park’s 50-year celebration is crowded into an eventful anniversary year in resistance and environmental justice history. On the same day that the park’s occupation began, Earth Day was declared, largely in response to the devastation of the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill. On Aug. 29, the Chicano Moratorium would end in the law-enforcement melee and shootings that led to the death of trailblazing L.A. Times journalist Ruben Salazar.

Over time, Chicano Park was acknowledged for its historical importance by local, state and federal preservation authorities, culminating in a prestigious National Historic Landmark designation in January 2017.

Enrique Morones, a longtime San Diego border activist and organizer, said he’s been going to Chicano Park since high school. To honor the 50th anniversary, he is hosting interviews with veteran members of the founding generation on a podcast, “Buen Hombre/Magnificent Mujer.” This week’s episode featured founding member Rigo Reyes.

“A lot of people are leaving us now, their age and so forth,” Morones said. “So it’s very important to record their history.”

Other longtime attendees are honoring the park in their own ways. La Bodega Gallery’s López-Chávez created a Chicano Park coloring sheet that she’s been distributing through Instagram. Local artist Bob Dominguez is putting together a visual history book of Chicano Park Day memories.

Online, friends have been sending messages of honor and affection to the Chicano Park community from near and sometimes very far. “I wish I was there, I wanted to have my 2nd trip to Califas, but it couldn’t come true,” wrote one user on the park’s general Facebook page. “Much love from Far East Side, Japan.”

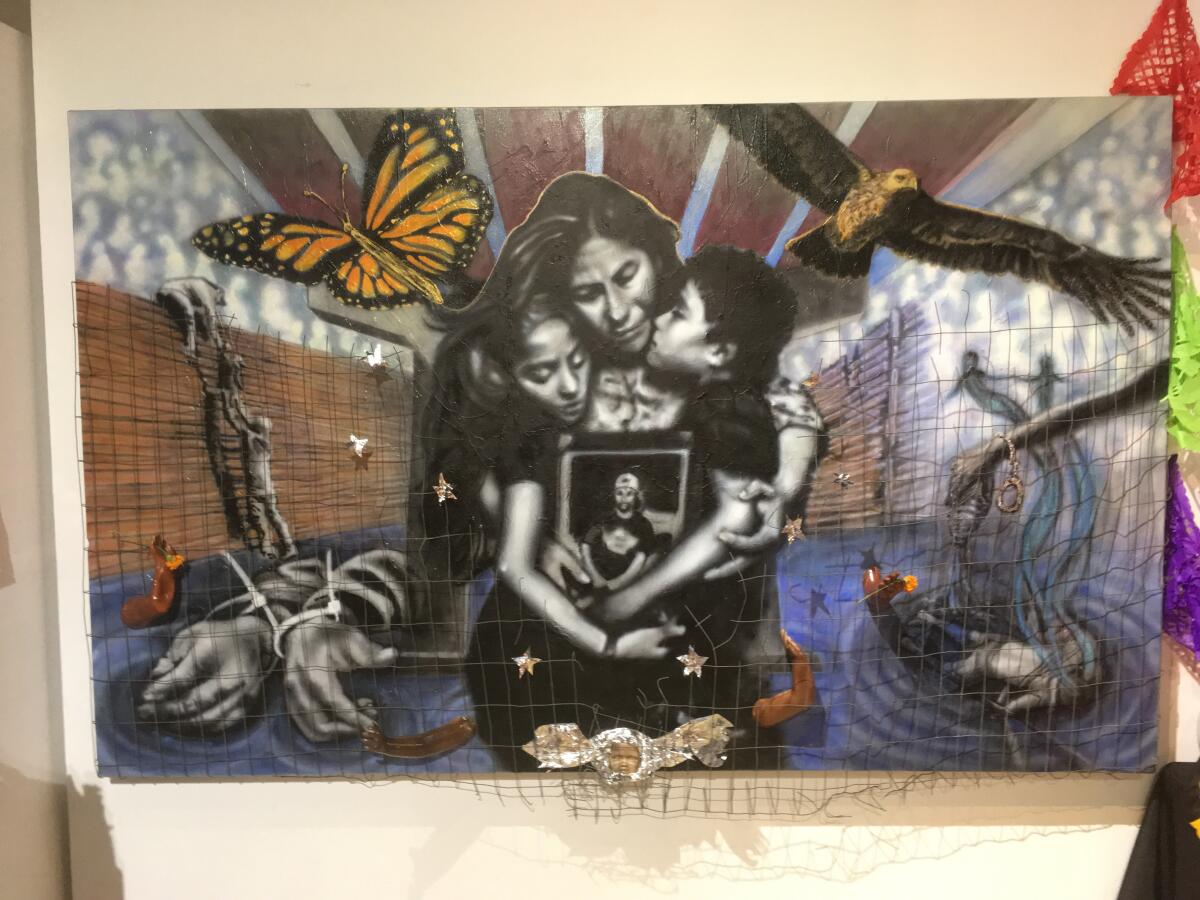

Yet there are signs of strain on the community from the wave of attention, or inattention. The murals have faced bouts of deterioration and neglect. In more recent years, far-right provocateurs have tried to spark confrontations at Chicano Park Day. And now a looming threat is the gentrification of Logan Heights. La Bodega, for example, had to close and change locations due to a rent increase. “We’ve seen a lot of residents be kicked out or businesses closed because rent was raised,” López-Chávez said.

The formation of Chicano Park also is considered a precursor to many of the community-led actions over green space and garden land in Latino urban centers that followed. Yvette Lopez-Ledesma, an L.A. native, experienced planner and advocate for green space in the San Fernando Valley, spent much of her childhood and teen years in San Diego County, where her parents still live.

She described the significance of the park in terms of the standard for equity that it set for environmental justice movements that reverberate today.

“It still warms my heart to see how that park is really by the community and for the community, and it hasn’t been easy,” Lopez-Ledesma said. “Anything dealing with land in this country is a struggle, especially when you have the pressures of displacement and gentrification.”

She said her mother would go to Logan Heights’ Our Lady of Guadalupe Church because it reminded her of her home in Los Angeles. In recent years, Lopez-Ledesma and other L.A. residents said they’ve noticed more people from the Los Angeles metro region taking time to visit or honor Chicano Park. It may become even more of a draw with the forthcoming opening of a Chicano Park Museum.

“Latinos [are] finding more spaces to put their voices out there,” Lopez-Ledesma said. “There’s this kind of reclaiming and resurgence, or Chicano culture coming back up, feeling proud.”

MORE ON CHICANO PARK

A YouTube post of the 1988 documentary “Chicano Park” is available available here.

Listen to the classic song by legendary locals Ramon “Chunky” Sanchez and Ricardo Sanchez, a.k.a. Los Alacranes, telling the Chicano Park story in song.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.