As a concert pianist, the stage is my life. But the pandemic taught me to love the livestream

- Share via

On Nov. 9, 1966, Alex Trebek famously interviewed a shy Canadian pianist by the name of Glenn Gould, who had boldly proclaimed the death of the live concert and retired into the confines of a recording studio. The Beatles had performed their last official concert at Candlestick Park in San Francisco just a couple of months earlier and settled at Abbey Road Studios (then called EMI Studios) to produce some of their most beloved work. Nothing could have been more shocking at a time when Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones were soaring to new heights with worldwide concert tours and Joel Grey was in previews playing the Emcee in “Cabaret.”

The past year of COVID-19 isolation has led many performers on a soul-searching quest for the true meaning behind artful communication. With the rise of passionate, stirring virtual performances delivered via smartphone cameras and mobile screens, we have been taken on an impressive backstage journey into the homes of the artists we admire most, humanizing the luminaries and cheering the underdogs.

One wonders, once again, just how essential a live, physical audience is to the larger puzzle. Can we forgo the social aspects of a concert entirely and still revel in its sheer capacity to thrill and engage?

After all, a concert is merely the tip of an iceberg — a peek into the state of mind of a performer at a particular point in time. Let’s not forget that one of the greatest concert pianists of all time, Frederic Chopin, gave only about 20 live performances in his lifetime, none of which took place in a gathering of more than a few hundred people. Some performers such as Glenn Gould detested the presence of audiences altogether and considered them a form of distraction, whereas more gregarious musicians such as Arthur Rubinstein appreciated the visceral connection that an audience brings to the experience.

I, for one, never would have survived the last months as a concert pianist if it weren’t for livestreaming. The outpouring of support from audiences as far away as Vietnam has inspired and energized my performances beyond my wildest imagination. What was once a lineup for autographs backstage has transformed into a steady stream of heart-shaped emojis onto the computer screen during each streaming session. At one point, by surrounding the piano with thick, black drapes and a few LED spotlights, I was even able to trick my mind into believing that I was on a live stage.

My first livestreamed concert from home, last April, was a disaster. I was quite excited about the idea as my good friend and trusted audio engineer, Steven Norsworthy, had just brought in a beautiful, handcrafted Fazioli F308 concert grand from Europe, also known as “the longest piano in the world market.” It seemed like the perfect instrument to kick off a new recital series — or so we thought.

On the day of the event, we miked the piano with its lid on full stick, turning the otherwise quiet living room into a tutti orchestra — and nearly blowing out our eardrums. For future sessions we stuffed small pieces of tissue paper in our ears and rubber foam pads under the piano.

Much more unsettling was the awkward bow and eerie silence that followed the 40-minute performance. Although I expected to receive comments about my specific interpretation of the four Ballades of Chopin, instead I read: “It keeps freezing” and “We can’t hear what you’re saying!” Sure enough, we had a lot to learn about livestreaming.

Over time, as the technical challenges subsided, I reveled in the sheer joy of reaching thousands of viewers scattered around the globe, which inspired me to take on greater artistic risks and reach a new level of musical intimacy in my virtual performances: improvising on popular tunes, taking requests from the audience and performing world-premiere works by living composers.

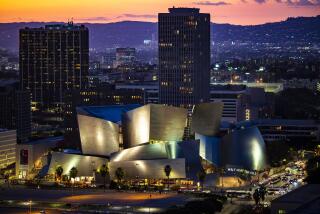

The limitations of technology are shrinking fast with improved internet connection reliability and the growing pool of gadgets at our disposal. Take LOLA, the low latency streaming system developed by Italian engineers in Trieste. It delivers networked performances between remote locations at close to the speed of light. You can even simulate the acoustics of L.A.’s Walt Disney Concert Hall — Row 7 — right from your living room using a digital audio workstation on your PC or Mac, together with an advanced signal processing plugin designed by Waves Audio.

Neighborhoods across the country are enhancing symmetric fiber-optic connections and 5G networks that can dramatically increase bandwidth capacity, and clever, bidirectional audio codecs such as Jack Audio are allowing musicians in different locations to jam together in near real-time.

But what about the audience experience? There is little like the anticipation that comes with going to a concert, taking your seat and giving whatever unfolds onstage your undivided attention. Sitting among strangers and sharing a common experience also creates a kind of spiritual oikos that generates a sense of belonging and heightened awareness. After all, the ultimate goal of a music performance is to unlock that semihypnotic state of nirvana, in which time comes to a standstill.

A few online experiments — including “The World Wide Tuning Meditation” by Pauline Oliveros and “Throughline” by Nico Muhly, a commission by the San Francisco Symphony — have attempted to show this altered state can come through a revelatory virtual experience. In due time, with the help of VR headsets and high-tech sound gear with advanced 3-D sound processing, the simulation of live concerts will transcend their own musicality and produce ravishing new expressions of art. Specially crafted pods built into future homes could block out external distractions.

In the case of piano recitals, the energy of the living room brims with life every instant that I “go live,” and my hands still sweat and shake at the first few bars of any piece of music, as they would onstage. I particularly love that virtual concerts provide my audiences with more control over their listening environments and plenty of opportunities to engage with me directly. I don’t miss the jet lag or the repetitive repertoire that come with live concert touring.

Ultimately, an artist’s need to produce art is like the poached egg to ramen — indivisible. The emerging world of virtual performance has given the arts greater prominence as a place of genuine solace and refuge. It has directed our focus inward and away from the harsh realities of the external world, in a virtual quest for that which binds humanity together.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.