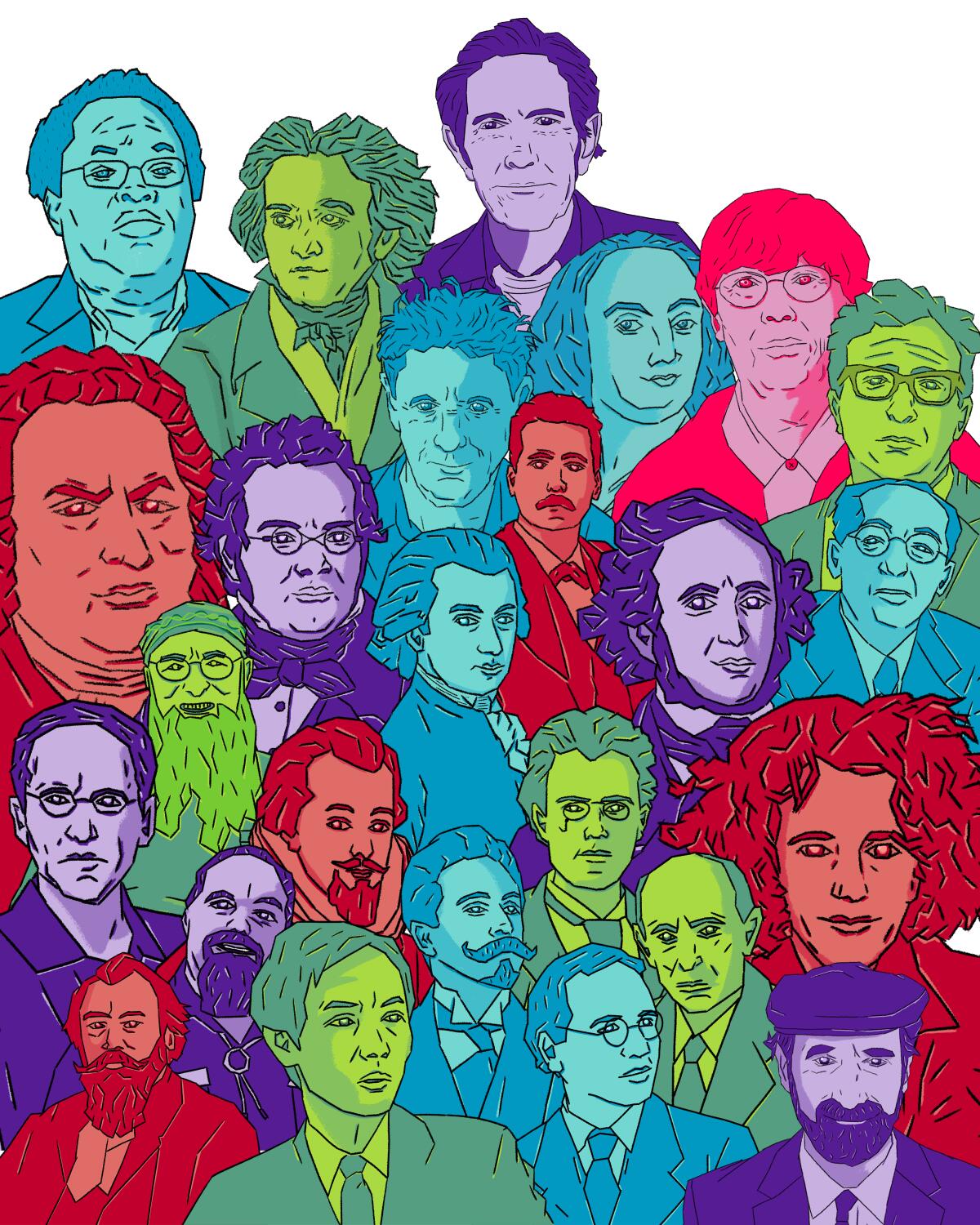

A ‘How to Listen’ wrap: What I’ve learned from six months of rehearing music favorites

- Share via

“How to Listen,” the six-month weekly series that dived into so-called classical music, was not my idea. The suggestion that I rely on a lifetime of listening to guide readers who may be interested in expanding musical horizons through my selection of pieces seemed a reasonable enterprise, although I had no idea how I would go about it.

I did, at first, resist titling it “How to Listen.” In the back of my mind was what Virgil Thomson liked to call the music appreciation racket. What I hadn’t counted on, however, was that the series would not be me telling you how to listen, but me finding out how to listen myself as I worked through 25 pieces that I figured I knew pretty well.

These pieces were chosen with a little, but not a lot, of thought. Diversity was an obvious necessity, because it is always an obvious necessity. Although it is too rarely viewed as such, classical music is, and has always been, the most diverse musical category in existence. Nothing is not allowed, no matter how many petty efforts through the ages to have it be otherwise.

That is one reason why I wanted the great permission-giver, John Cage, to be a guide. I selected only one Cage piece, his String Quartet in Four Parts, a relatively conventional one at that, yet he lurked throughout the series. A few pieces of music specifically give context to our times. But mostly I instinctually picked out of a hat of longtime favorites, some so longtime that I hadn’t heard them in years and didn’t really know if they’d still be favorites. When it came to scheduling — with the exceptions only of Halloween (Scriabin’s “Black Mass” piano sonata) and Christmas (Messiaen’s glances at the infant Jesus) — variety was my main objective. There was no preconceived notion that they would serve as a kind of diary of the pandemic mind-set, although “How to Listen” might be read that way.

Each week ultimately became a process of reacquaintance. I discovered I didn’t always remember pieces as well as I thought I would. I had given my editors very short descriptions of why I had selected each work, and I wound up sticking to almost none of that. A newspaper critic’s activities mostly revolve around reacting to something someone else considers worth our attention. In this case, I had no one to blame but myself.

What I found is that nearly everything I listened to resonated in ways I hadn’t anticipated. Cage’s call for us to hear everything around us in everything we hear was certainly helpful. I wasn’t alone. Many critics approached Cage’s silent piece, “4’33”,” emblematic of the early days of the pandemic, when industrial noise and traffic diminished and ears perked up to the wonders of environmental sound.

It soon dawned on me that I was no longer in the realm of how to listen but that of why we must listen. The central tenet in Cage’s philosophy of art — and, for that matter, of life — is the essential need to pay attention. Listening really does matter. That message, moreover, was all around us. Black Lives Matter demanded we listen. Epidemiologists told us to listen to them, and we did in the quiet early days of the pandemic. As it’s gotten noisy again, and we’ve gotten distracted, doctors are now pleading that we listen ever more carefully to their dire warnings about how to mitigate the horror befalling our hospitals. Paying attention is everything.

Isolation surely had something to do with my listening. Music was no longer just music, but a reflection of what seemed to be going on. Piece after piece sounded like it had been written to reflect the last six tumultuous months. I chose Machaut’s luminous “Messe Notre Dame,” for instance, because it helped to show where our music came from. It hadn’t occurred to me that it was written not six months ago but six centuries ago, in the wake of the Black Death pandemic.

The same goes for Berio’s “Sinfonia” memorializing Martin Luther King Jr. I love the fact that just as musicology students were calling to cancel Beethoven for promoting white male European domination, “How to Listen” turned to composer Pauline Oliveros, who had written a marvelous retort in her rollicking 1974 composition: “Beethoven Was a Lesbian.”

It also was nice to have made note of the influence of blaxploitation film on Olga Neuwirth two months before Melvin Van Peebles’ “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” was selected by the Library of Congress for the National Film Registry. Who would have thought in advance that Schoenberg’s “Pierrot Lunaire” might reflect the clown-show aspects of Washington politics?

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

Maybe it was being stuck at home that unconsciously caused me to make this series California-centric, but I don’t think so. One way we listen is by making connections, and the West Coast has played a far more outsize role in classical music than it is credited. Connections couldn’t be ignored.

Cage, of course, was born in L.A. and came of age here. His teacher was Schoenberg, who fled Nazi Germany for Los Angeles. Mahler championed the young Schoenberg. Lou Harrison, who also studied with Schoenberg, came to personify California music.

Little Mills College in Oakland overachieves. The genesis of “Sinfonia” came from the period when Berio taught there in 1960s. (One of his students famously was Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead.) A decade later Terry Riley joined the Mills faculty, and it was there, thanks to Kronos Quartet being in residence, he began his string quartet odyssey. Mills also gave Oliveros, who performed in the premiere of Riley’s “In C,” her academic start. George Lewis’ distinguished academic career got a big boost from UC San Diego. Neuwirth counts as one of her major influences John Adams, with whom she studied at the San Francisco Conservatory.

Hollywood can’t be ignored. Copland, who wrote memorable film scores, was there around the time of “Appalachian Spring.” The ballet was written for Martha Graham, whose dance life began at the Denishawn School in L.A. It is inexcusable to have left out not only Adams but also Stravinsky, who lived in L.A. longer than any other city, but that’s life.

Another surprising trend was how lasting modal harmony, using scales other than the commonplace major and minor, has proved to be. We began with Beethoven, who employed the Lydian mode in his Opus 132 for out-of-body illusions. We ended with Riley, who used the Dorian mode in “Sun Rings” for out-of-this-world access.

Machaut may have relied on ancient musical modes because that’s what composers had to work with in the 14th century. But there are modal instances in Frederic Rzewski’s “The People United Will Never be Defeated,” in “Sinfonia,” in Cage’s Quartet, notably in Takemitsu’s “November Steps” and Dowland’s “Lachrimae,” in the references to Chinese music in Puccini’s “Turandot,” in Neuwirth’s “Masaot,” in Harrison and in Copland and, faintly, in Philip Glass’ “Einstein on the Beach” and Mahler’s Eighth Symphony. Modal harmony is not unwelcoming in Lewis’ improvisations nor Oliveros’. Golijov’s “Ayre” has got it all, modes of all sorts. When Schubert starts trilling at the bottom of the keyboard, you can hear whatever you’re inclined to hear in the rumble.

What does this say about classical music? We trace modes back to ancient Greece, which makes modal harmony as classical as you can get. But there is also modal jazz. Rock musicians have employed modal harmony. (Frank Zappa sure did.)

We cannot escape history. We can refuse history, as Berio noted in one of his Norton Lectures at Harvard, but not forget it. The way to listen to these pieces in an upside-down year is now history too. Listening is always in the present. But the fact is that 25 semi-casually selected composers (and the hundreds more that just as easily could have been), writing six centuries ago or a last decade, have relevant wisdom to impart if we are willing to, as Cage recommended, pay attention. He also said every seat is the best seat in the house.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.