Movies are the 20th century’s greatest art form. So says this ludicrous LACMA exhibition

- Share via

“City of Cinema: Paris 1850-1907,” a modestly scaled exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, opens with a bizarre juxtaposition. The pairing doesn’t bode well for what follows.

On one side of the doorway is a small, pleasant and routine urban landscape from the early 1870s by Berthe Morisot, a gifted painter who was just then working toward the translucent light and color that would later characterize her best Impressionist work. The picture, “View of Paris From the Trocadéro,” shows a young girl, her back to us, looking out over France’s capital city from a hilltop position across the meandering Seine. Two fashionably dressed bourgeois women lean on a nearby railing, chatting.

On the other side of the entry, a Lumière film clip from the late 1890s is projected high up on the wall.

Shot by (or for) the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, the black-and-white clip shows busy Parisian street life from an aerial vantage point. People bustle about below, going to and fro beneath tiled roofs. The scenes were filmed from a tethered hot air balloon, a fashionable leisure pastime of the day.

Apparently, we’re to draw some insightful connection between these two views of the city — one in static paint on canvas and the other in a moving picture shot a couple decades later. What or why is anybody’s guess.

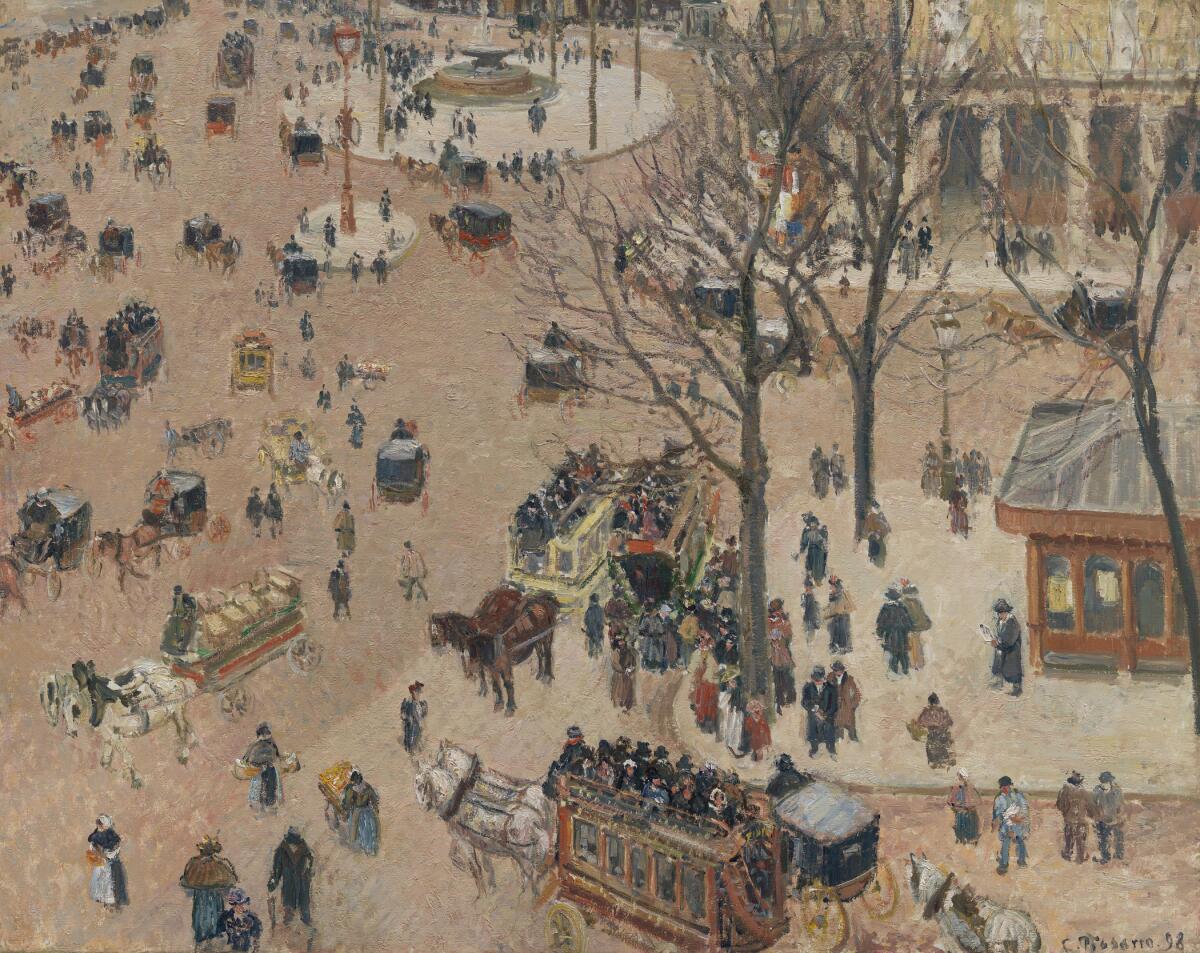

The two images, one still and one moving, have roughly zero to do with each other, aerial views of rural and urban landscapes having been a global artistic staple just about forever. (Camille Pissarro’s great aerial view of the Place du Théâtre Franҫais, painted from a second-floor hotel room and also in the show, is a favorite in LACMA’s collection.) Surely, it’s mere coincidence that a century later, Telluride, Colo., has an influential annual film festival as well as a popular annual balloon festival.

Turns out the juxtaposition’s purpose is anybody’s guess only until reading the show’s introductory text, posted on the wall in between them. It’s a jaw-dropper.

“Bringing together a wide range of the artistic expressions and visual materials that helped create a receptive audience for the new medium,” we’re earnestly instructed, “this exhibition traces film’s evolution from a disposable entertainment to the twentieth century’s greatest art form.”

What? LACMA is telling us that movies toppled painting and sculpture to became last century’s “greatest art form”? The show will reveal how it happened, and we’re expected to believe it.

Hollywood is no slouch in the grandiosity department, but even the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, LACMA’s new neighbor next door, knows better than to try to pull that one. Pandering to Hollywood is a disheartening if common spectacle, but the exhibition’s claim is absurd on its face.

A great movie is a great movie, a great painting is a great painting. Period. The suggestion that movies and paintings can somehow be compared to determine which should carry the title of representing “the twentieth century’s greatest art form” is ridiculous.

The show was jointly organized by LACMA and the Musée d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie in Paris, where it appeared in a somewhat different version last fall. That the lame assertion comes from museums charged with apprehending art’s histories at their deepest and most meaningful level renders the institutions farcical.

The jumbles that unfold in the show chronicle familiar themes. One is the spectacle of modern bourgeois life in Paris, a city then recently transformed from a grimy medieval labyrinth into a glistening network of broad urban boulevards. Another is the emergence of purpose-built movie theaters around 1907.

Mostly, such themes have nothing useful to offer.

Take the film clips of lively “serpentine” dances in swirling silk garments popularized at the Folies-Bergère by Illinois expat Loie Fuller. The clips are paired with unexceptional small sculptures of the dancer engulfed in rippling bronze rather than gossamer robes. The pairing underscores Fuller’s superstar celebrity, soon eclipsed by the tragic Isadora Duncan, strangled by her scarf. But it also seems intended to demonstrate sculpture’s forlorn failure to measure up to a motion picture’s nimble capacities for displaying movement.

Nearby, that ostensible deficiency gets reiterated in an 1889 tabletop sculpture by Auguste Rodin and an 1890 oil sketch by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Both show a popular scene from Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.” In the miraculous story, a sculpture carved by an artist comes alive — as it would in an 1898 film by Georges Méliès. The sculptor and the painter can represent the miracle in immovable marble and paint, but finally only a filmmaker can show the metamorphosis happening over time.

And so it goes, throughout the show. Perhaps the most demoralizing moment comes at the end.

Have you ever seen the famous 1895 Lumière film of a train pulling into a station, which legend says sent terrified audiences scurrying for fear of being mowed down? Two of a dozen exceptional Claude Monet paintings of the Gare Saint-Lazare, both showing a train at the station engulfed in clouds of industrial steam, hang side by side. One locomotive environment is relatively bright and crisp, the other dissolves into a hazy blur.

Nearly 150 years after Monet put down his brush, the brilliance of his 1877 construction of the scene with broken brushwork of violets, blues, pinks, grays, whites, yellows and blacks continues to glue eyeballs. Monet opened the door to a whole new way of seeing.

By stark contrast, no one these days runs screaming from a movie theater to escape certain ruin from the moving picture of an onrushing choo-choo. Instead, we grin at the Lumière film’s charmingly calculated quaintness, which opened the door to today’s mass sensation of Disney’s Marvel Universe.

Does longevity of effect mean one art form is better or worse than the other? No; it means paintings and movies are different from each other, not comparable art forms in some spurious contest of cultural greatness.

Movement was the very essence of cinema, while being static has its own obvious virtues. Regrettably, the show’s two best paintings (by a light year) are relegated to also-ran status on a side exit wall. The Monets just don’t fit the loony thesis that film would evolve into the “greatest art form” of the last century. Catch a glimpse of them on the way out the door.

In a version of the common riddle “Which came first? The chicken or the egg?,” the show suggests that Parisian urban spectacle fueled creation of the cinema. A 1981 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, “Before Photography: Painting and the Invention of Photography,” which attempted something similar for the still camera, was rightly panned.

What actually happened to generate the birth of movies and their wild popularity? Forget about the city as spectacle or serpentine dances. They’re next to irrelevant.

The newly expanded Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego is a revelation, with an impressive permanent collection and a sharp Niki de Saint Phalle show.

Instead, the explanation is banal. Motion pictures were just the next obvious step in industrial technology. Once commercially practical processes for still photographs had been invented (circa 1839), and cameras became ubiquitous throughout society, photographs that could move were inevitable.

That development in engineering history took less than a generation.

“City of Cinema” does feature as a centerpiece a 1972 reconstruction of an “optical theater,” a fascinating (and complicated) mechanical device that employs revolving mirrors and hundreds of drawings to make projected animations. Émile Reynaud, a Parisian industrial designer, invented it in 1888.

Would engineering advances like this make for a compelling art museum show? Probably not.

Reynaud’s contraption is a diverting curiosity, meant to produce disposable commercial entertainments — which it does in a spectral cartoon’s sweet love triangle, regarded as the first animated film. (Titled “Poor Pierrot,” its original run was in a Paris wax museum.) But watching the ghostly little movie, it’s difficult to imagine that a tech show would be as constructive for Hollywood pandering as an art museum exhibition endorsing unsurpassed greatness in the coming century.

Oh, and I almost forgot. One more thing. A disposable commercial entertainment of a digital sort turned up just a generation after 1907, when the LACMA show ends. Whatever happened to TV?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.