- Share via

The most accessible and reliable material an artist has is their body. A body can be used to stage a self-portrait, a parade or a dance. Bodies can function as canvas or they can support an elaborate costume. Bodies are flexible and dynamic; they elicit desire and revulsion. Race, gender and sexuality imbue them with an array of social and political meanings. Art about bodies is almost as old as the body: Some of the oldest art in the world consists of simple stencils of hands in ancient caves.

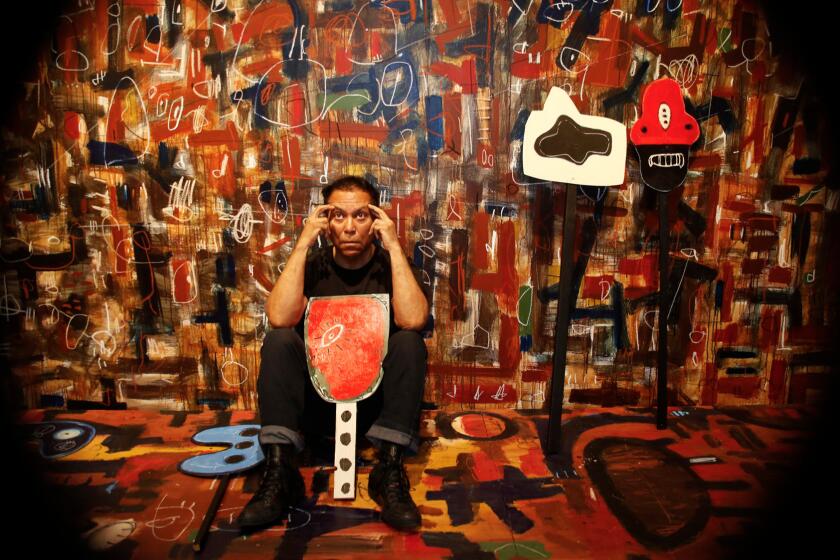

For Chicanx artists in the 1970s, working with few resources and little institutional support, the body was an elemental material. For contemporary artists it remains a potent subject. Two exhibitions currently on view in the Southland — “Teddy Sandoval and the Butch Gardens School of Art” at the Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM) in Los Angeles and “Xican-a.o.x. Body” at the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture in Riverside — provide a groundbreaking look at the ways several generations of Chicanx artists (along with a handful of their colleagues in Latin America) have employed the body in their work.

Together, the shows reveal an array of philosophies, identities and formal approaches. Bodies appear as points of historical inquiry; they convey bawdiness too. In the Sandoval retrospective, close inspection of a charming little drawing of palm trees on 8th Place in Long Beach reveals their fruits to be not coconuts, but pert penises. (8th Place was a famed cruising spot.)

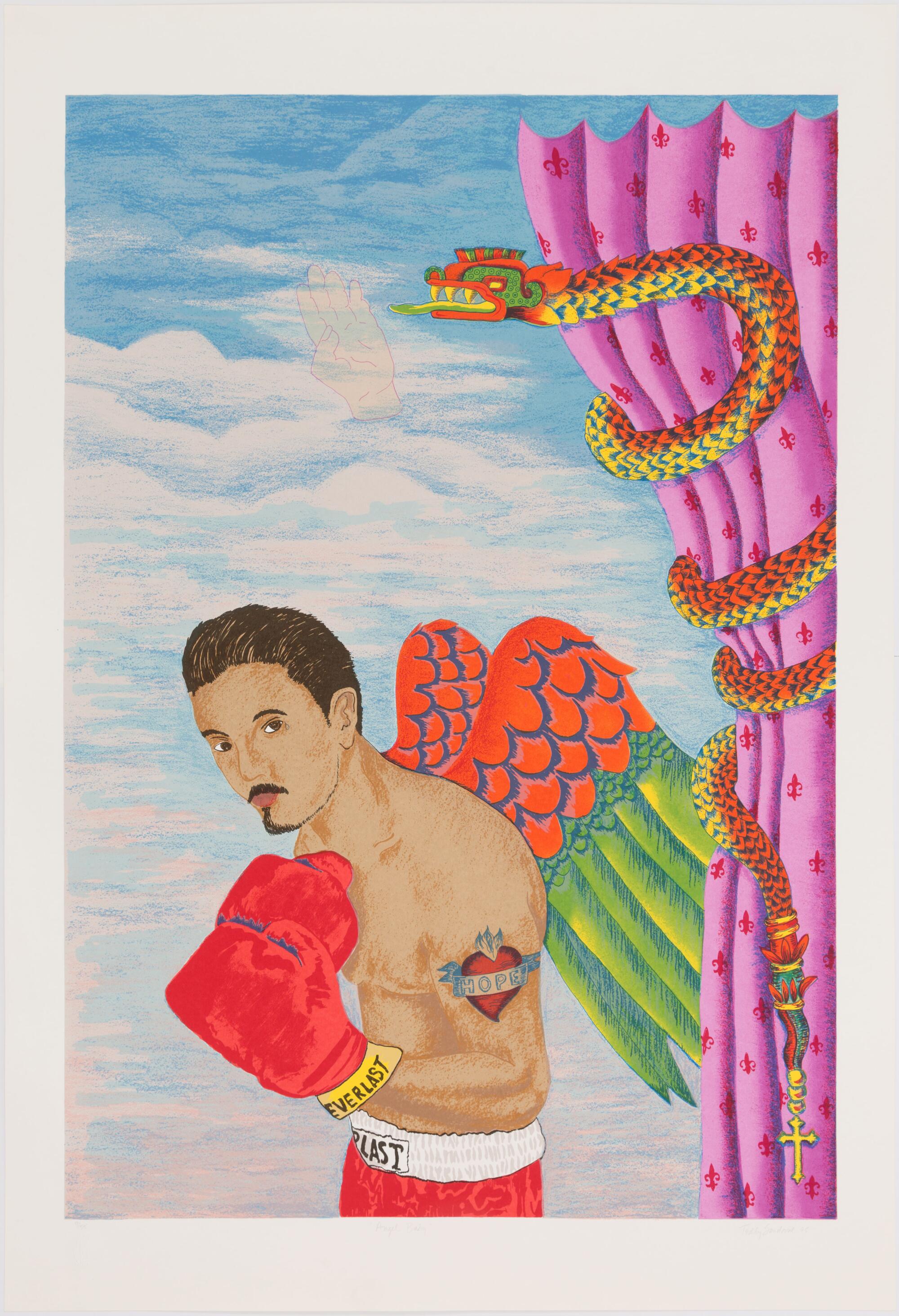

Sandoval, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1995, toyed with signifiers of ethnicity, gender and sexuality in his work. He was Chicano, gay and out — and his work serves as a compelling link between the two exhibitions. The VPAM show, his first retrospective, features a large number of pieces that have never before been exhibited publicly. At the Cheech, he is represented by a pair of works: a watercolor of a Maya warrior in a scrotum-hugging thong; and “Angel Baby,” a mournful print from the year of his death that shows an angelic young boxer framed by sky and a pink curtain. A print from that edition is also on view at VPAM.

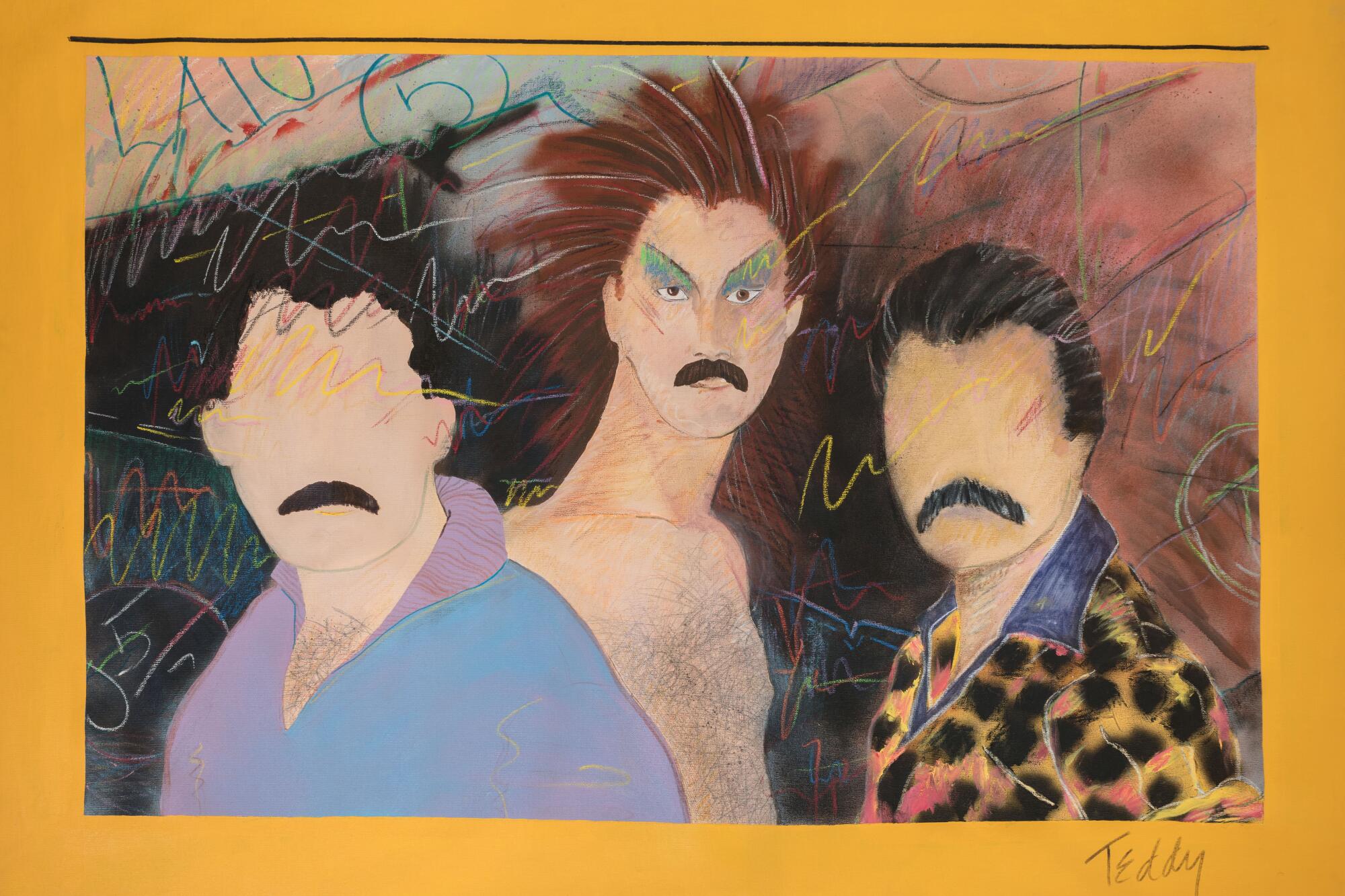

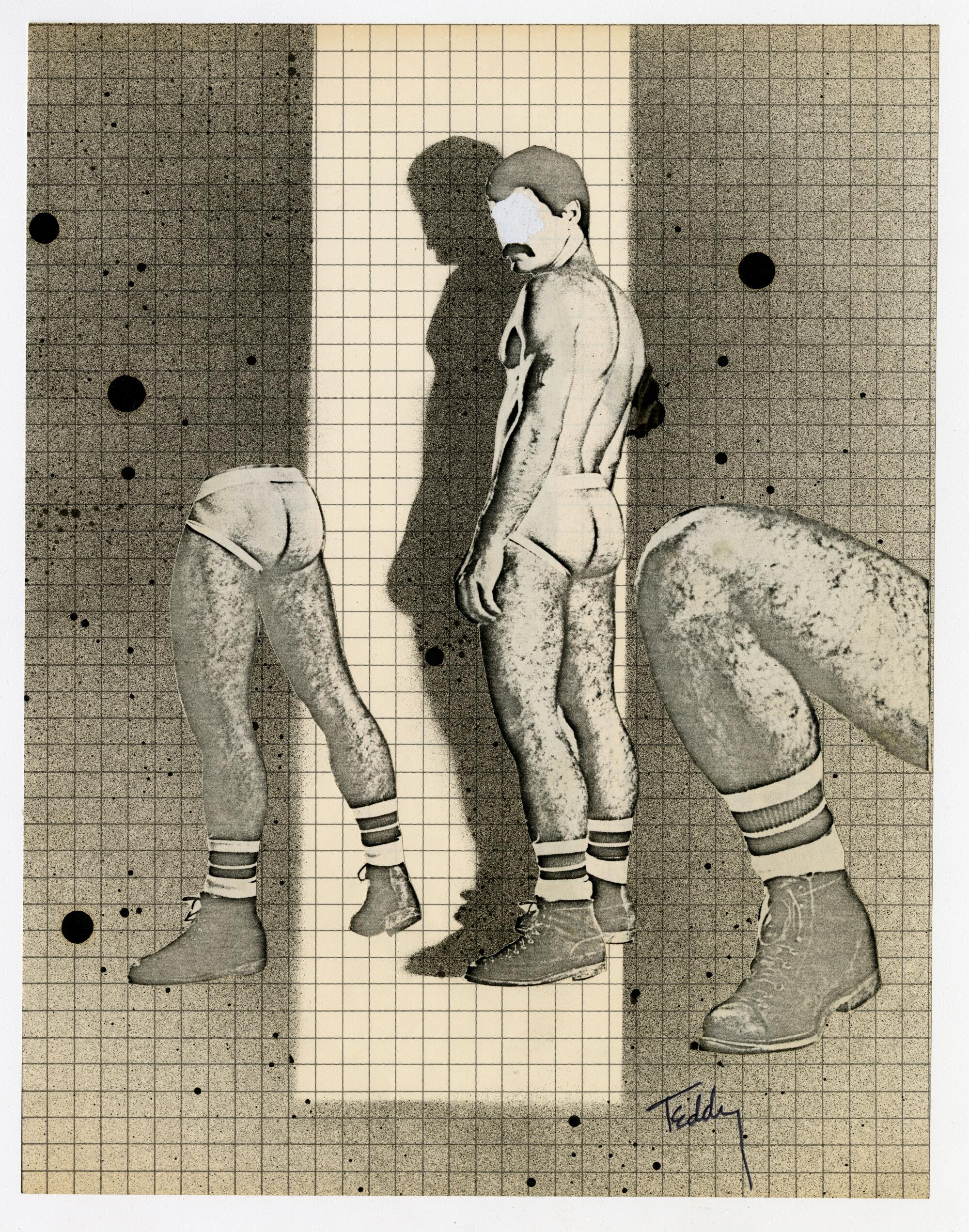

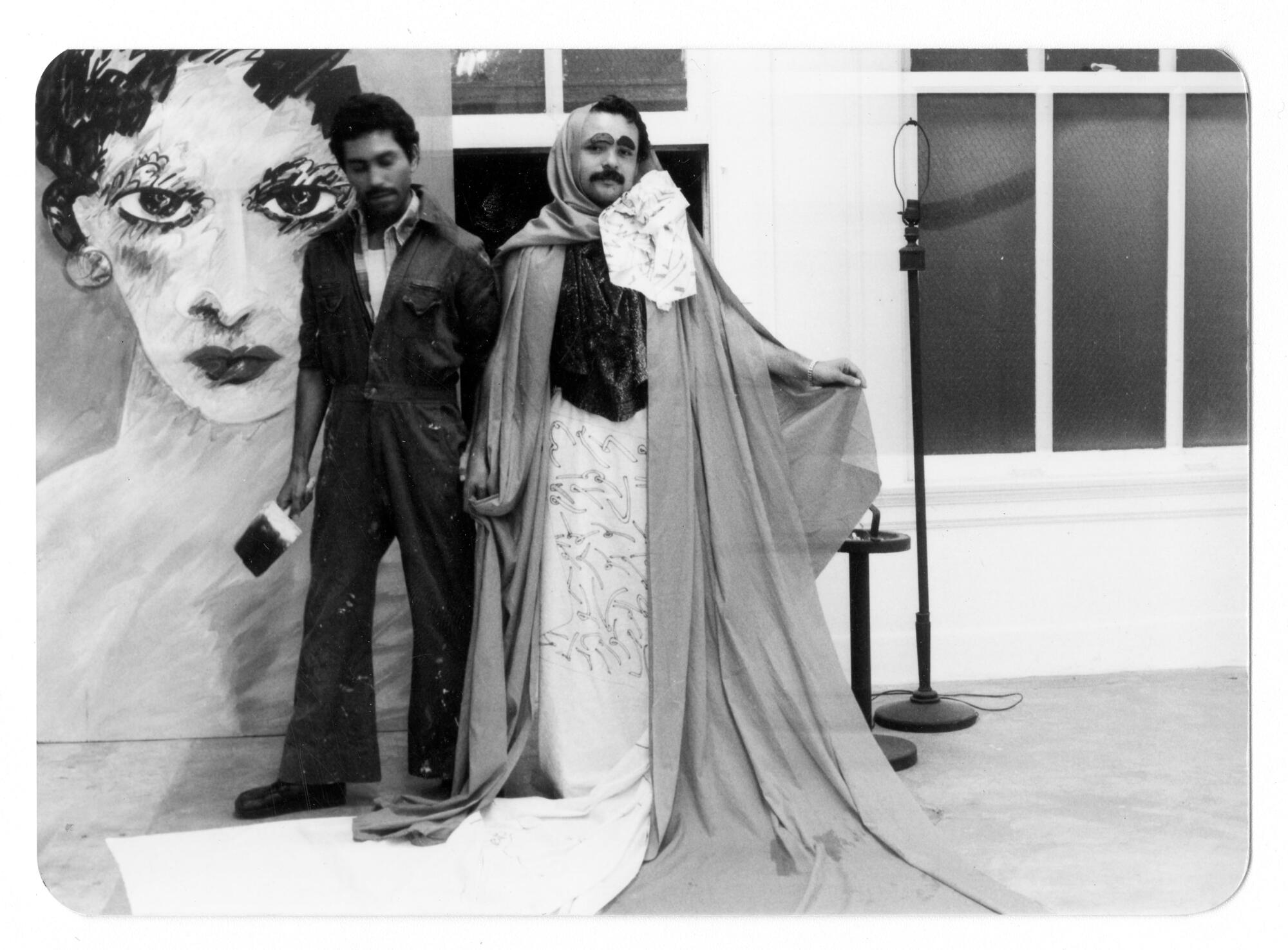

Sandoval is a good jumping-off point for any discussion about the body; he deployed it in so many ways. He had a drag persona named Rosa de la Montaña and he created a faceless, mustachioed avatar that embodied the hypermasculine “clones” of the ‘70s gay scene. With fellow artist Gronk (Glugio Nicandro), he staged a conceptual photography piece inspired by Frida Kahlo — at a time when Kahlo was not yet a household name. He also designed materials for the San Francisco music label Moby Dick Records and created provocative illustrations for gay lifestyle publications. As historian Robb Hernández once wrote, in Sandoval’s work you’ll find an “unapologetic representation of the Chicano phallus.”

“Teddy Sandoval and the Butch Gardens School of Art” was organized by curators David Evans Frantz and C. Ondine Chavoya. (Chavoya marks another conjunction with the Cheech: He contributed an essay on Chicanx camp for the “Xican-a.o.x. Body” catalog.) Chavoya and Frantz were behind the illuminating 2017 exhibition “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.,” which explored overlapping circles of queer Chicanx artists (including Sandoval) over three decades. And they have once again produced an instructive (and highly enjoyable) show on an artist about which too little was known.

Sandoval worked across a range of media, producing paintings, prints, collages, mail art, graphic design and ceramics — often emblazoned with recurring symbols and logos. (Behold the ironic, penis-shaped ceramic chili peppers!) On the whole, his work queered Chicanx culture while also Chicanx-izing queer culture. His faceless, mustachioed cipher synthesizes the archetype of the clone with the prominence of the facial hair as a signifier of masculinity in Mexican culture.

Gronk is an artist who has never been stuck on a single style of art-making.

His art is dead serious but also wickedly playful. Butch Gardens, for example, was a ‘70s-era gay bar in Silver Lake (slogan: “Are You Butch Enough for Butch Gardens???”) whose name Sandoval borrowed for an invented academy called “The Butch Gardens School of Art.” He used the academy’s fictitious imprimatur on everything from mail art to the shows he organized and co-hosted as Rosa de la Montaña (whose name echoes Marcel Duchamp’s famed alter ego, Rrose Sélavy).

Throughout the retrospective, the curators have sprinkled in work by other artists. There are pieces by Sandoval collaborators such as Joey Terrill, an L.A. painter who created the tongue-in-cheek zine “Homeboy Beautiful,” which featured absurdist queer advice columns and fictional exposés. And there are artists whom Sandoval never met, including Colombian Álvaro Barrios, who crafted a homoerotic zine called “Coquito” out of photos harvested from the sports pages. The additions provide context and introduced me to some intriguing Latin American artists.

The exhibition has a wealth of material, but I found myself most taken with an early self-portrait the artist produced in 1976. It features three tiny lithographs mounted on paper that show Sandoval standing before L.A. landmarks such as City Hall and the Church of Our Lady Queen of Angels. In one, his head is thrown back in a gesture that could be interpreted as laughter or ecstasy; in another, he wears a mantilla and prays. He is a budding queer icon among icons, a Chicanx body inhabiting the body of L.A. in funny, subversive ways.

Lesser-seen works by Chicano artists illuminate. Plus, Robert Egan leaves the vaunted OPC, and the Getty repatriates works, in our weekly arts newsletter.

“Xican-a.o.x. Body” — now in its final days at the Cheech — picks up where Sandoval left off.

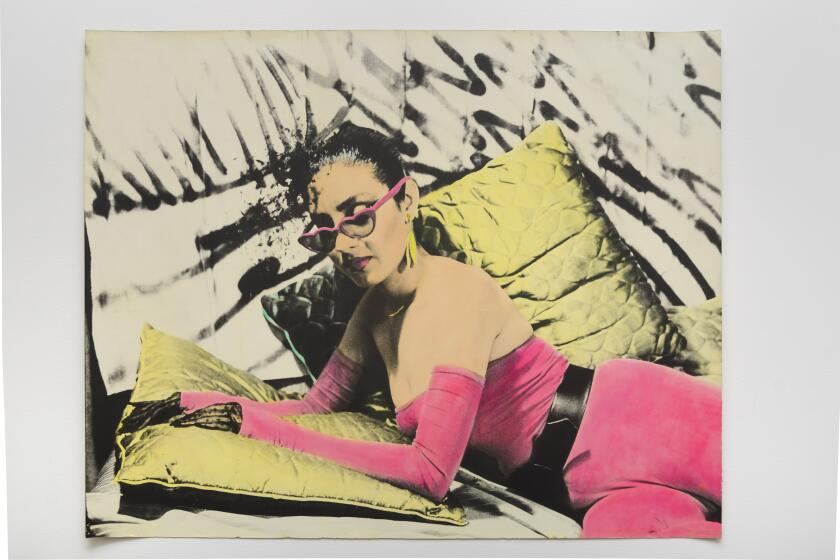

Organized by independent curator Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, with Marissa Del Toro and Gilbert Vicario, the show is threaded with the work of artists from Sandoval’s social and artistic circles. This includes Cyclona, the ribald drag persona of Robert Legorreta; John Valadez, whose ‘70s-era photographs captured the modish aesthetics of Eastside youth; and Patssi Valdez, who, with Gronk, formed part of the influential conceptual group Asco. Valdez is represented by a self-portrait that shows her skeptically side-eyeing the camera, as well as a video titled “Hot Pink” depicting a crew of glamorous postpunk collaborators bending gender and ethnicity. (Stills from this saturated pink film grace the cover of the catalog.)

Collectively, their images capture the ways Chicanx artists have seized upon stylized self-presentation as a way of countering racism and exclusion. As Del Toro writes in the catalog, “the Xicanx body exists as a refusal of assimilation and the violence of erasure.”

Artists from the ‘70s and ‘80s are elemental to “Xicana-a.ox. Body,” but work from the ‘90s and the new millennium complete the picture.

Ephemera from a 1994 performance by Sacramento-born Celia Herrera Rodríguez explore Indigeneity in relation to the body; grainy videos capture ‘90s-era performances by experimental punk band Cholita!, which featured Vaginal Davis as lead vocalist and Alice Bag on guitar. (Be sure to stick around for their single “I’m Not a Puta, I’m a Princess.”) A series of remarkable photographs by Sandra de la Loza, originally created in 1999, shows images of protest projected onto her nude form — body and body politic merging into one. And cryptic paintings by Salomón Huerta from the early 2000s reveal only the back of his sitters’ heads, denying the gaze of the viewer.

Particularly striking is a 2019-20 sculpture by artist José Villalobos that takes aim at a prominent symbol of masculinity: the cowboy boot, which is as emblematic in northern Mexico as it is in the United States. For “Botas/Boots,” the artist used rose- and lavender-scented glycerin soaps to sculpt a pair of translucent boots; within them, he embedded bits of barbed wire and blades. The piece jabs at the toxic nature of machismo while scrambling the boundaries of gender. On a material level, they are absolutely alluring.

For the L.A. artist, ‘Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser’ is a hopeful work. ‘I feel like this piece has everything about building a lowrider car that’s exciting, like decisions about how you want your body adorned, how you want this car to look.’

While the work is often engaging, the exhibition’s framing is muddled. “Xican-a.o.x. Body,” as the curators point out in the catalog’s introductory essay, is not a comprehensive art historical survey of the Chicanx body in art. Instead, the show revolves around a series of loose themes, such as in-between states, conceptions of brownness and the Chicanx figure in Pop. In some cases, the themes simply don’t jell. (The section on Pop felt like a thesis for a different exhibition.) In other cases, individual works didn’t connect to the show’s grand narrative. Justin Favela’s piñata lowrider “Gypsy Rose Piñata (II),” from 2022, is an eye-grabber, but its connection to the body felt like a stretch.

There are nonetheless some incredibly potent moments. A gallery featuring works related to resistance is beautifully installed. There, De la Loza’s powerful bodily protest images hang within view of Ken Gonzales-Day‘s elegant photographs of California hang trees. (Sometimes the absence of a body can be just as poignant as its presence.) A sculpture by Narsiso Martinez titled “Magic Harvest,” from 2019, occupies the center of the room. It is crafted from fruit packing boxes, the sort emblazoned with bold logos and appetizing names like “Wonderful Sweet Scarletts Grapefruit.” Martinez arranged these into a tower, adding larger-than-life monochromatic figures of farmworkers in ink and charcoal — figures that appear almost spectral against the bubbly graphic design. Martinez takes bodies often rendered invisible and makes them central to the narrative.

And that is what ultimately makes “Xican-a.o.x. Body” — as well as the Teddy Sandoval show at VPAM — worth seeing. As Chicanxs remain underrepresented in popular culture, their bodies frequently criminalized, these exhibitions offer complexity and nuance. The Chicanx body is many different types of bodies — filled with beauty, resilience, rage and marvelous, burning desire.

'Xican-a.o.x. Body'

Where: The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture, 3581 Mission Inn Ave., Riverside

When: Through Sunday

Info: riversideartmuseum.org

'Teddy Sandoval and the Butch Gardens School of Art'

Where: Vincent Price Art Museum, 1301 Cesar Chavez Ave., Monterey Park

When: Through March 2

Info: vpam.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.