Should Rembrandt, Van Gogh help bail out a bankrupt Detroit?

- Share via

DETROIT — The Christie’s appraisers enter on Mondays, when the museum is closed, and either inspect what’s on the walls or ask to see some of the thousands of works not on display, sometimes sending Detroit Institute of Arts technicians on half-day missions to find pieces in deep storage and prepare them for examination.

People on the local cultural scene tend to think that it won’t happen, that the city ultimately won’t sell off some or all of this world-class art museum’s collection to help cover the more than $18 billion in debt obligations cited in Detroit’s recent bankruptcy filing.

Selling a Van Gogh, a Rembrandt, a Matisse — unthinkable, no? They wouldn’t irreparably tarnish what may be Detroit’s prime cultural gem just as the city is positioning itself to bounce back like its previously bankrupt car companies have done, would they?

“That’s ludicrous. That’s crazy,” Antonio Agee, a graffiti artist who works under the name Shades, says while mingling with fellow artists and designers at the Detroit Design Festival’s opening-night party in the former General Motors Research Laboratory, one of the city’s many repurposed historic buildings. “The DIA is the best thing we’ve got. We can bounce back without selling art. People who say they’re going to sell art don’t believe in the city. I believe in the city.”

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Yet starting in mid-September there they were, those visitors from Christie’s, paid for with $200,000 of the broke city’s money after Kevyn Orr, appointed by Gov. Rick Snyder as the city’s emergency manager in March, prompted Detroit’s bankruptcy filing in July and announced in early August that he had hired the New York-based auction house to appraise the DIA’s collection.

Such a sell-off would be unprecedented in the U.S. museum world, which operates under a code of ethics that allows the selling of artworks only for the purpose of buying more art. But then again, much of what’s going on in U.S. history’s largest municipal bankruptcy is unprecedented.

“There’s really nothing to guide us,” DIA Director Graham Beal says as he sits in the recently renovated Kresge Court, a former cafeteria and party room transformed into a lounge resembling a Tuscan courtyard. “This is all untested.”

The DIA — unlike other major art museums such as the Art Institute of Chicago, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art — is city owned. Detroit has given it little or no money in recent years, but no matter: The museum belongs to the city.

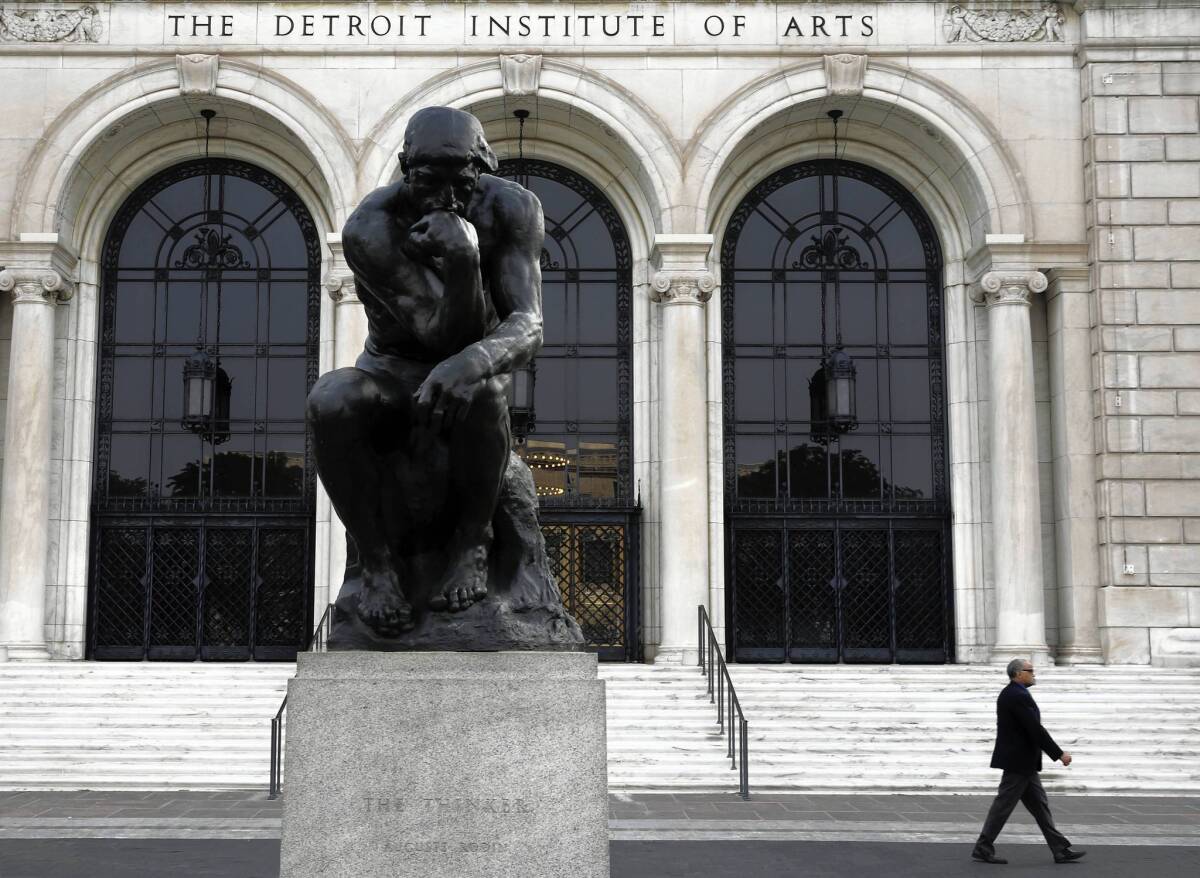

Many Detroiters would agree with that statement, that the museum belongs to the city, to them. The inscription above the DIA’s grand entrance reads: “Dedicated by the People of Detroit to the Knowledge and Enjoyment of Art.”

Many residents of the surrounding suburban counties would contend that the DIA belongs to them as well. In August 2012, voters in Wayne (which includes Detroit), Oakland and Macomb counties approved a property tax to fund the DIA for 10 years — this at a time when the population had not proved particularly keen on voluntary tax increases. The millage is supplying $23 million of what Beal says is the museum’s $31-million annual budget. Residents of those counties get free admission.

So the suggestion of selling artistic masterworks to pay off city debts is opening many cans of worms in Detroit and beyond. Even setting aside the will-they-or-won’t-they proposition, some see danger in where this conversation is heading, with art pitted against city services and retirees’ pensions, if not also the interests of municipal bondholders who made investments that went south.

Can art’s value be measured in terms of what it would fetch at auction, or does it provide something far greater if less measurable to a community, particularly one desperately seeking a rebound? Is it appropriate to discuss art as a balance-sheet asset, or is this controversy yet another sign of a money-obsessed culture? Or in times like these, when a city can’t afford to respond promptly to 911 calls or to keep more than 60% of its streetlights working at any one time, should everything be put on the table?

“The city must know the current value of all its assets, including the city-owned collection at the DIA,” Orr said in a statement upon announcing the museum appraisals. “There has never been, nor is there now, any plan to sell art. This valuation, as well as the valuation of other city assets, is an integral part of the restructuring process.”

“Kevyn Orr has said he doesn’t want to sell the art,” Beal says, “which is not the same as saying, ‘I’m not going to.’”

True enough. On Oct. 3, Orr told the Detroit Economic Club that the DIA had to figure out a way to leverage money out of its collection. “I’m deferring to them to save themselves,” the Detroit Free Press quoted Orr as saying, “but if they don’t, I’ll take them up.”

Neighborhood anchor

With its dramatic staircase, fountain and Auguste Rodin’s “The Thinker” statue fronting the Woodward Avenue thoroughfare, the white-marble DIA anchors Detroit’s resurgent Midtown neighborhood, standing among the sprawling Wayne State University campus, the College for Creative Studies, blocks upon blocks of medical facilities, and new businesses, galleries and restaurants that have been popping up in recent months and years.

The story outside Detroit is that in declaring bankruptcy, the city has hit a low. The story inside Detroit is that the bottoming-out actually happened years ago and that an influx of artists, designers, entrepreneurs and developers is infusing new energy into Downtown, Midtown and maybe even some of those horribly depleted neighborhoods.

ART: Can you guess the high price?

Drive north from Downtown through the area historically known as the Cass Corridor, and you see abandoned, boarded-up, graffiti-laden buildings but also freshly minted Midtown storefronts sporting an art gallery, a soon-to-open tapas place and the boutique for Shinola’s high-end watches and bicycles manufactured nearby.

“It’s a crazy, vibrant art scene, and it’s such a difficult message to communicate: The city is bankrupt, the DIA may have to sell off artworks, yet artists are moving here in droves,” says Elysia Borowy-Reeder, executive director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, which opened in 2006 a few blocks south of the DIA in a high-ceilinged former auto showroom.

Amid the bustle of the Design Festival kickoff, designer-artist Bethany Shorb says she moved to Detroit from Boston for graduate school 14 years ago and chose to stay. When she tells people in other cities that she lives in Detroit, “people say, ‘I’m sorry.’ I’m not,” she says. “It’s my chosen, adopted home.”

Essayist Marsha Music, whose artist-husband, David Philpot, moved to Detroit from Chicago a year ago, says the city’s decline of industry has had a positive effect on its artistry. “In a way, the art in Detroit has been untethered from commercial and industrial fetters of past decades,” she says.

Many Detroiters have grown weary of “ruin porn”: photos shot among Detroit’s estimated 78,000 abandoned buildings thought to be beyond salvage. The city’s preferred theme is its inevitable rebound.

“NOTHING STOPS DETROIT” reads the red neon sign in the window of the Detroit Shoppe, a temporary souvenir/local goods store downtown. One downtown high-rise wall boasts the several-stories-tall slogan “Outsource to Detroit,” referring to businesses taking advantage of the city’s relatively low overhead.

To Matt Clayson, director of the Detroit Creative Corridor Center, the DIA is central to the creative work energizing the city. “The DIA is fundamental to all of this,” he says. “It’s our cultural conscience.”

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

As Beal stands in the DIA courtyard surrounded by Diego Rivera’s celebrated “Detroit Industry” murals, an older woman in a motorized chair calls to him: “Don’t let them sell any of your artwork!”

The British-born Beal, who arrived at the DIA in 1999 after serving as director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, can envision a domino effect that would begin with the DIA being forced to sell one piece of art and end with it closing its doors.

Oakland Country officials have said that they will withhold its $10-million annual contribution to the tri-county $23-million millage if the museum sells art, because they haven’t planned for that money to go toward Detroit’s debts. Officials from Macomb Country (contributing $5 million) have echoed that sentiment, while Wayne County ($8 million) officials have said that they also might reconsider.

The yanking of that money, Beal says, shutters the museum.

The millage had been Beal’s Hail Mary pass in the first place, as he said he’d already taken the DIA’s annual budget from $34 million to $25 million at one point and laid off 25% of its staff. A strategic planning analysis from 2007 showed that the prospect of trimming an additional $5 million from the budget “effectively closed us,” Beal said, so he instead set out to convince the metropolitan Detroit area — which, given the city’s lack of tourism, supplies the bulk of the museum’s audience — of the DIA’s worth.

He toured replicas of various masterworks around far-flung communities and made the case to residents that the DIA “belonged to them, literally.” The communities responded by funding the museum.

“That shows that art and culture and the DIA are valued in the community,” Borowy-Reeder says. “It’s a big stamp of validation. And then for [selling art] to be put forward as an appropriate measure to get out of bankruptcy or to help solve some of the bankruptcy problems is really troubling.”

Another complication is that the Assn. of Art Museum Directors, which accredits the DIA and other North American art institutions, offers two “fundamental principles” regarding the deaccesioning of art:

“The decision to deaccession is made solely to improve the quality, scope, and appropriateness of the collection, and to support the mission and long-term goals of the museum.

“Proceeds from a deaccessioned work are used only to acquire other works of art — the proceeds are never used as operating funds, to build a general endowment, or for any other expenses.”

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

When the National Academy in Manhattan sold two paintings for financial reasons in 2008, the association asked its members not to lend artworks to the academy or to collaborate with it on exhibitions.

In May, the association released a statement condemning a possible DIA art sale: “Art collections are vitally important cultural and educational resources that should never be treated as disposable assets to be liquidated, even in times of economic distress.”

Ford Bell, the Washington, D.C.-based president of the American Alliance of Museums, says the museum field has worked hard to convince the Financial Accounting Standards Board, which sets standards for how private organizations should prepare financial reports, that museum collections not be included as assets.

Beal notes that the DIA never considered selling artwork during previous financial crises — such as during the Great Depression or in 1975, when the museum had to close for a month— so he doesn’t see why the museum now should have to pay for problems created elsewhere.

Orr has criticized many aspects of the city’s financial management, including nearly $1 billion in bonuses paid from Detroit’s pension fund. Beal notes that the DIA has been managing and funding its own employees’ pensions since 1997, when the museum ceased being a city department.

“It’s been painted as the either/or — the DIA or the retirees,” Clayson says. “But it’s the DIA and retirees or the sophisticated bondholders who lend an insolvent city a lot of money. We can’t fall into that trap of retirees versus art.”

Todd Levin, a Detroit native now based in New York as director of the Levin Art Group, argues that a DIA art sale likely wouldn’t improve the lives of residents. “What they’re trying to do is use the money that would be generated by the sale of art as a bailout for these bondholders, saying, ‘You made a risky bet, you were wrong, and we’re making you whole anyway,’” Levin says.

Says Beal: “You could sell the whole collection, and it wouldn’t come close to satisfying anything. Creditors might get a higher percentage of their misguided investment in the city of Detroit, but it’s a fraction of the total debt.”

In the meantime, Levin speculates that the sold pieces could wind up as assets “for the .0000001%.”

“There are very few institutions that could afford to spend $100 million on a masterpiece work of art,” the art consultant says. “The question becomes who could afford art works at that price point? It’s ultra-wealthy individuals who might purchase this work, take it out of the public view and put it in their private boudoir. Such work might disappear into the annals of time for generations.”

A recent Detroit News story noted that although the city also owns the Detroit Zoo, it is not appraising the animals as assets, perhaps because a giraffe couldn’t fetch close to what a Van Gogh might.

Out of the DIA’s 60,000 pieces, 6,000 are on view, and 3,300 are classified as city of Detroit purchases rather than those donated by patrons, though Beal notes that patrons contributed to those city funds as well.

Christie’s is appraising only the city-purchased works, so Rivera’s courtyard murals, a gift from Edsel B. Ford, are not at risk, but many of the DIA’s most famous paintings — such as Van Gogh’s straw-hatted “Self Portrait” (1887), Rembrandt’s “The Visitation” (1640) and Giovanni Bellini’s “Madonna and Child” (1509) — were bought by the city before the museum’s 1927 opening.

Speculation has been that the Van Gogh might be worth $80 million to $100 million, though Beal says the museum’s most valuable work could be Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “The Wedding Dance” (1566), a milestone piece from an artist seldom on the market. Beal figures that if the emergency manager really wants to make a dent in the massive debt, it’s these types of pieces — rather than less notable and valuable ones in storage — that would be sold.

Whether the sale happens or not, Beal regrets the injection of dollar figures into the art-viewing experience. “I think it is the overall monetization of everything,” he says. “If you say to someone [the Van Gogh] is worth $80 to 100 million, that’s what they remember. Well, that’s not why it’s in this building. It’s in the building because of what Van Gogh said [artistically] when he was painting it.”

In June, Michigan Atty. Gen. Bill Schuette issued a 22-page opinion stating that “The art collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts is held by the city of Detroit in a charitable trust for the people of Michigan, and no piece of the collection may thus be sold, conveyed, or transferred to satisfy city debts or obligations.”

Some observers doubt that the governor, who appointed Orr, would want the political heat that would accompany a DIA sell-off. A Free Press/WXYZ-TV poll conducted in late September indicated that 78% of Detroiters opposed the sale of DIA art and that 75% opposed city workers’ pensions being reduced to pay down the debt.

Orr’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

Levin notes that most high-end art sales involve multiple appraisals, so he questions whether a bankruptcy court would sign off on just one party doing the valuations, particularly one with a vested interest in selling the pieces. “You can’t just have one group who also is a seller come in and do this,” he says.

Recently, some folks have been floating the idea of the DIA selling art and leasing it back — a suggestion reinforced by Orr’s comments to the Economic Club. Beal finds no small irony in the notion that instead of government supporting the arts, an arts institution might be expected to pay the government’s bills.

“We run this museum at no cost to the city, which takes about $35 million a year, so it seems to me that we’re already morally leasing the collection,” Beal said over the phone in mid-October. (That figure includes an additional $4 million spent each year on expenses.) “There’s no way we would pay extra money just to have the art.”

He says that before the counties’ millage vote, he investigated the prospect of such a buy-and-lease arrangement but found no takers. And even so, he says, “you rent it for, what, 20 years to somebody? And then the great works of art all go away.”

Beal doesn’t intend to be around to see that happen. “I cannot stay under those circumstances,” he says, noting that for the city to sell the DIA’s art, it either would have to persuade the museum’s board of directors to approve such an act or it would have to cancel the 1997 contract that empowered the nonprofit Detroit Institute of Arts Inc. to operate the museum.

If the latter were to occur, Beal says, “we cease to run the DIA, and the city of Detroit gets a $35-million operation back on its books.”

Well, no one expected this recovery business to be easy. Not in Detroit.

Twitter @MarkCaro

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.