Two decades after Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao, where does architecture stand?

- Share via

The story of

That’s the day disastrous flooding hit the Basque city, adding urgency to a nascent plan to rethink the civic role of the heavily polluted Nervión River, which cuts through the heart of Bilbao. That effort ultimately carved out new territory along its banks for parks and cultural buildings — including Gehry’s otherworldly museum.

Or maybe it’s necessary to go back even further, to the middle 1970s, when Bilbao, then still a powerful steel town, a sort of Basque-country Pittsburgh, began sketching out plans for a new subway and rail network. After an international competition in 1988, a consortium of architects and engineers led by London’s Foster and Partners created the new Bilbao Metro, which opened in fall 1995 — two full years before the Guggenheim. The network now consists of three lines and 41 stations.

There are other pre-Guggenheim dates that shouldn’t be overlooked either. In the early 1990s, a pair of new planning bodies were formed — Bilbao Metropoli-30 and Bilbao Ria 2000 — to wrangle policy among the city, the nearby port, the rail company ADIF and the Basque regional government. Their task was as easily defined as it was overwhelming: Imagine a post-industrial future for a swiftly failing industrial city.

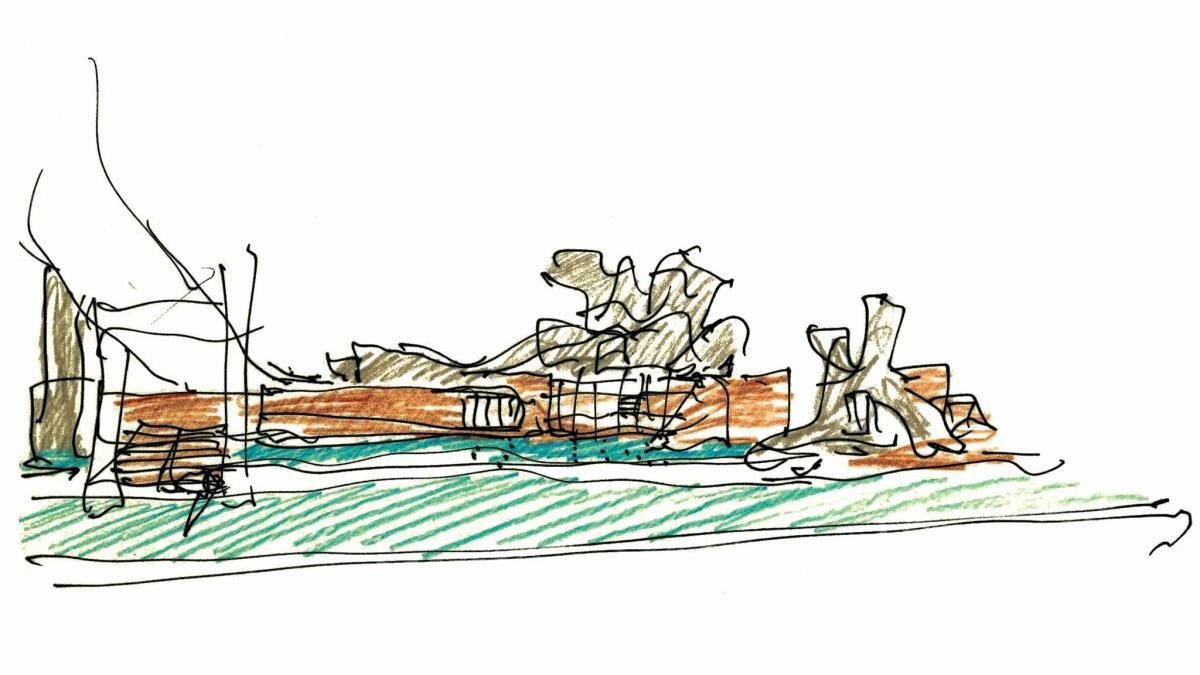

All of which is to say that when the city and the Guggenheim put together a design competition for a new branch of the museum in 1991, several crucial pieces of urban planning and regional ambition were already or soon to be in place. Gehry beat out two other finalists: Tokyo architect Arata Isozaki and Austrian office Coop Himmelblau. Strikingly enough, the same three firms would wind up being reunited along Grand Avenue in Los Angeles, with Isozaki’s Museum of Contemporary Art, which predated the Bilbao competition, later joined by Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall (2003) and Himmelblau’s high school for the arts (2009).

As architect and writer Koldo Lus Arana argues in an excellent special issue of the journal MAS Context marking the museum’s anniversary, Gehry’s Guggenheim, which opened on Oct. 19, 1997, was an overnight success several decades in the making. Properly measuring the museum’s impact requires — in a way that’s much different from typical architectural anniversaries — telling the story of what came before as much as what came after.

And the truth is that even all these years later, most stories don’t do this. Instead, they tend to trumpet the “Bilbao Effect” — the way the success of Gehry’s museum convinced other cities they needed a similarly spectacular cultural landmark to drive publicity and tourism — as if it were an exclusively architectural phenomenon. The staggeringly photogenic quality of Gehry’s design — particularly as seen looking down Bilbao’s Iparraguirre Street, tightly grouped and once-sooty 19th century buildings giving way to the shimmering profile of the new museum — has made this line of thinking only more tempting.

That’s not to say that the Bilbao Effect isn’t real. At least in Bilbao. It’s tough to say how portable it is — many cities have overinvested in flamboyant trophy buildings since 1997, just as many architecture firms have become all too expert in delivering them — but in local terms there’s no denying the impact. And it’s an impact, significantly, that hasn’t worn off: The museum continues to attract about a million visitors per year, more than 85% of whom come to Bilbao from outside the region.

The numbers dipped after the 2008 economic crisis but have rebounded strongly. The two months with the highest attendance in the 20-year history of the museum have both come in recent years, in July 2012 and July 2014.

Still, Lus Arana is correct to argue that it makes more sense to speak of the “Bilbao Anomaly” than the Bilbao Effect. The convergence of architectural, planning and economic factors was essentially perfect.

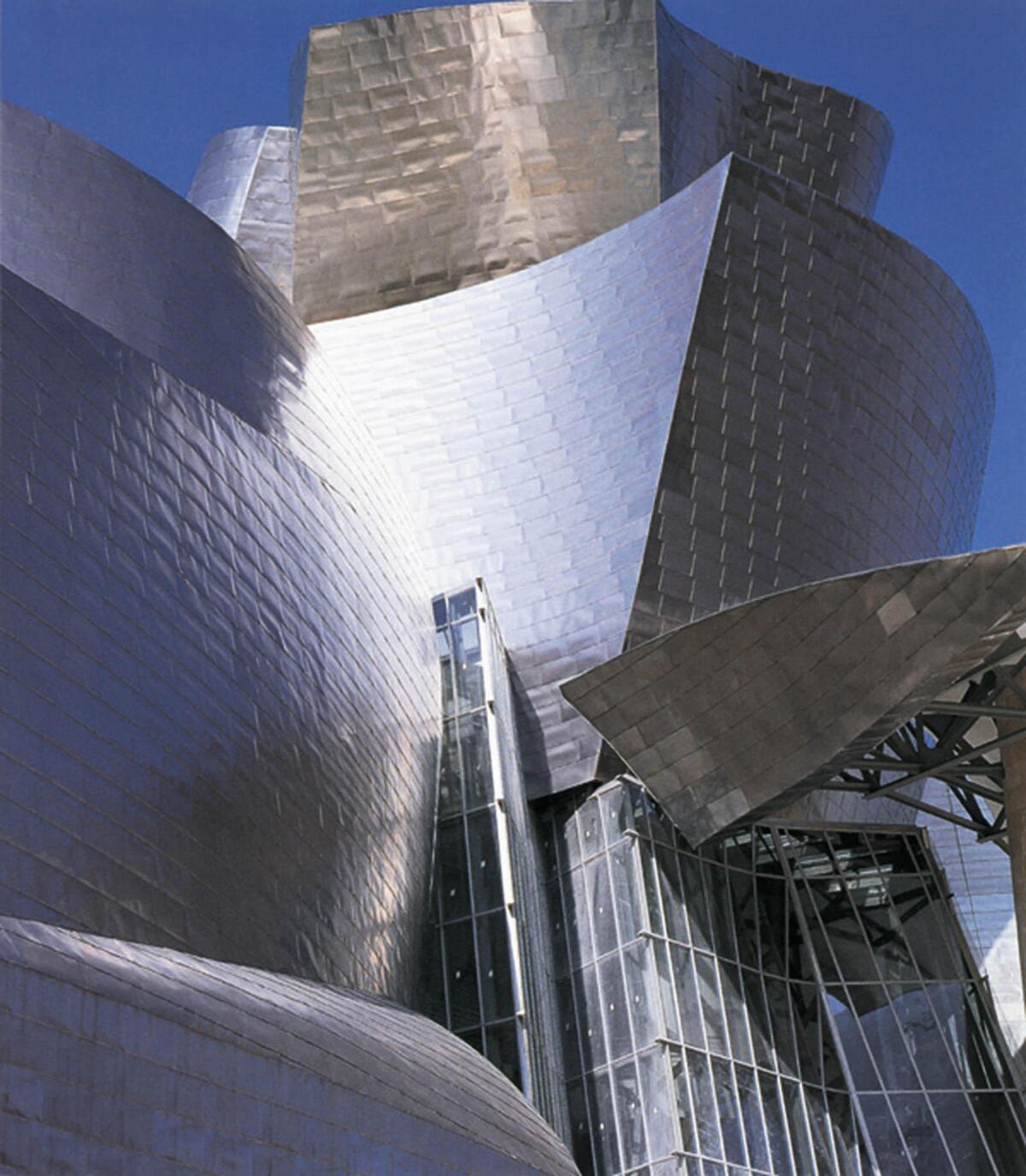

Even the museum’s titanium skin, which adds immeasurably to its dynamic personality, the way its appearance shifts depending on the quality of light and the time of day, is the product of luck. Just as the construction drawings for the building were being issued, in the mid-1990s, Russia decided to sell its entire titanium reserve, sending prices plummeting.

All the same — even as we acknowledge everything that led up to the event itself — it would be hard to overestimate the shock waves that the opening of the museum sent through the architecture world 20 years ago.

The timing wasn’t just perfect for Bilbao in 1997. It was also perfect for Gehry, a 68-year-old architect who’d already won a Pritzker Prize but whose work had never entirely captured the imagination of a wide public, a designer who was just beginning to learn how to harness digital technology to build the complex curves that would become his signature. And perfect for an architecture profession that had been mired for much of the 1990s in a kind of malaise, unsure where to head next after several years of recession and how to escape the increasingly banal and uninspired cul-de-sac of postmodernism.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

I still remember with almost perfect clarity the morning 20 years ago that I picked up the New York Times Magazine to see a significant chunk of Herbert Muschamp’s review printed in large type on the cover, beginning with this sentence: “The word is out that miracles still occur.”

It sounds hyperbolic now — and goodness knows Muschamp, more than most critics, was capable of overdoing it — but it really did feel miraculous, the idea that there was all of a sudden a building that the whole world seemed to be talking about, that your parents and your neighbors knew about along with your architect friends. Architecture had lost that cachet during much of the 1990s.

I was in mid-20s at the time, living in a rental house in Oakland, writing about architecture whenever I could but mostly making a living as an editor. Muschamp’s review gave me permission to think that a career writing about architecture full-time was possible. And when I moved to New York the following year with my now-wife, to take a fellowship in arts journalism at Columbia University, it was immediately clear that the Guggenheim had changed everything for an aspiring architecture critic like me. All of a sudden, most major magazines in New York had decided that architecture and design were subjects they could no longer afford to ignore (as some had done, frankly, for roughly a decade by then). For a short while it even seemed, speaking of miracles, there were more architecture assignments than writers to take them on.

I made my own pilgrimage to Bilbao a couple of years after the museum opened and found it not just as architecturally powerful as advertised but also a surprisingly subtle fit for its riverside setting. The museum — and this is also often overlooked — suggested not just a new ambition and charisma in Gehry’s work but a new clarity. And maybe a new understanding of how architecture, increasingly a game of images, needed to be played as the 20th century gave way to the 21st.

Gehry’s trademark extroversion was still there, the same wild geometries and garrulous quality, but it was newly focused, contained. Instead of a jumble of forms clad in a jumble of materials — Gehry’s familiar Rauschenbergian approach — the unruly shapes were wrapped, across much of the building, inside a consistent and mesmerizing titanium skin. This made all the difference, especially in terms of first-glance impact. A daring poem has more force if it’s printed in one typeface, not seven.

The effect was easy to measure in Los Angeles as well. The Guggenheim’s rapturous reception essentially shamed city leaders here into raising the money needed to finish long-stalled Disney Hall — a building that was designed well before Gehry’s museum in Spain but would open to the public six years after it.

What if the concert hall had been finished first? Would the full Bilbao Effect, with all its benefits, have been ours to enjoy instead?

As any careful study of the Guggenheim makes clear, the answer is probably no. Los Angeles simply hadn’t laid the planning groundwork for our Gehry landmark nearly as well as Bilbao (which is one reason Disney Hall was so long delayed in the first place). Pre-Bilbao, a Gehry concert hall on Grand Avenue would have generated lots of attention; it wouldn’t have changed the fortunes of a region and its economy.

One last thing. We tend to forget how downtrodden architecture felt in the mid-1990s, before the Guggenheim opened, in part for a paradoxical reason: because the museum helped make the field such a recognizable force and presence in popular culture. Its lasting influence has obscured its original power, how much of an out-of-the-blue savior it seemed.

The resulting post-Bilbao ubiquity of architecture and famous architects (Gehry designed jewelry for Tiffany and appeared on “The Simpsons”) turned out to be its own trap, sapping the field’s political power and social conscience even as its hip quotient grew. There’s a new book from Columbia University Press, edited by Esther Choi and Marrikka Trotter, called “Architecture Is All Over.” The title, of course, has a double meaning: architecture is everywhere and nowhere, stylish and impotent, feted and spent. That split personality is a Bilbao Effect too.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.