Seven photos, seven stories: Chris Killip on capturing the declining industrial towns of England in the ‘70s and ‘80s

- Share via

When Chris Killip decided to become a photographer at the age of 17, he had never taken a picture. “I didn’t own a camera,” he recalls. “Nobody in my family had cameras.”

But seeing a single image by seminal French lensman Henri Cartier-Bresson persuaded him that photography was what he needed to be doing.

“I was looking at the pictures of the Tour de France in Paris Match and I came across this photo by Bresson: ‘Rue Mouffetard, Paris,’” Killip says, referring to Cartier-Bresson’s 1954 image of a buoyant little boy carrying bottles of wine. “It really puzzled me. Why did it have such an allure? I couldn’t have said anything about it except that it had a grip on me.”

It was the 1960s and at that moment Killip, who was born in England on the Isle of Man, gave up on his father’s dream of learning hotel management and began taking pictures — first as a beach photographer at a local resort, then as an assistant to commercial photographers in London. A fateful trip to New York that included a visit to the photo collections at the Museum of Modern Art inspired him to take pictures “for its own sake.”

Killip wanted to make art.

A grant ultimately led him to northeastern England in the 1970s, where he began to photograph old towns that had once been home to coal mines and mills, but which were at that moment in a period of steep decline.

They are at the tough end of things, the people in my photographs. It’s about the struggle for work, being out of work, fighting for work.

— Chris Killip, artist

“I had this very big plate glass camera with a very big flash,” Killip says via telephone from Harvard University, where he has taught for 26 years (and from which he is about to retire). “I looked like something that had fallen out of the 1950s. I was very visible.”

Despite the conspicuous getup, Killip nonetheless was able to capture vivid slices of daily life: men fishing, kids playing, punks dancing, scavengers gathering coal on a beach.

“They are at the tough end of things, the people in my photographs,” Killip says. “It’s about the struggle for work, being out of work, fighting for work.”

Images from those series were gathered in the book “In Flagrante” in 1988, which has been described as “the most important book of English photography from the 1980s.”

The book was re-released by Steidl last year — and Killip’s photographs (along with contact sheets and other ephemera) are currently on view at the Getty Museum, in the exhibition “Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of ‘In Flagrante.’”

The exhibition couldn’t come at a more poignant time in the United States — where issues of de-industrialization and poverty are now on the political front burner.

Unfortunately, there are other parallels too. As occurred in his native England, Killip says U.S. politicians are not contending with the issue of de-industrialization in forthright ways.

“To talk about revitalizing coal mining is cuckooland,” he says. “The miners’ strike in England in 1984 wasn’t about money. It was about what are you going to replace it with when you close it down? … You can’t go back to how things were. But how can you plan on a better future for more people? I don’t see this happening.”

Killip’s photographs are rich with history and with stories. The photographer took time to tell the stories behind seven of his photographs — and they are as good as the images themselves, offering tales of illicit horse racing, a mournful fisherman’s ritual and some very odd nights at a punk club.

Cart and horse

Killip spent years documenting a community of workers who harvested loose coal from a beach in Lynemouth, a coastal village in northeastern England. The coal was the detritus left by a local mining concern. Initially, the artist was chased off the beach whenever he showed up with his camera. But he was eventually allowed access after a a towering local figure named Trevor Critchlow intervened on his behalf.

In the photograph “Gordon and Critch’s Cart,” the photographer captures a friend of Critchlow’s named Gordon, who is in the midst of harvesting the coal that bobs around the surf. “He’s watching me photograph him,” says Killip. “Gordon I knew very well.”

The technique used by the “sea-coalers,” as they are called, was something that immediately caught the artist’s eye when he landed in the area.

“Coal floats,” he explains. “And they have this wire mesh net that they use to capture the coal. It was a very strange sight because they are using horses and carts and it seems so 19th century. But the ground in that area is very soft and vehicles could sink, so horses and carts were preferable.”

The very good coat

Over time, Killip not only photographed the sea-coalers, he came to live among them in an encampment on the edge of town. There, he became good friends with a couple named Brian and Rosie Laidler, who often fed him dinner despite their limited means. Staying with the Laidlers for a time was a woman named Moira, whom Killip captured harvesting coal in a fur coat, an image that is as much about form and textures as it is a story of survival.

“It seems quite ironic in this very nice fur coat to be picking coal,” says Killip. “[Moira had] gotten it from her mother who didn’t wear it anymore. And it was always referred to as ‘the very good fur coat.’”

A story of place

Killip’s photographs capture not just people but the settings in which they lived. In 1976 in Yorkshire, he snapped a photo of a row house before a coal plant. It is striking for its detail: the soot-filled air, the rows of old doors used as a garden fence, the happy Christmas ornament that hangs over the row house door.

“As I was taking the picture, this little face appeared in the window,” he remembers. “I have one without anyone in it and the one with the child in it. And [the latter is] a much better picture. It makes the building a home.”

“Interestingly, that’s the coal mine that the sculptor Henry Moore’s father would have been a coal miner,” he adds. “Moore writes quite movingly about watching his mother bathe his father in a tin tub in the house. Seeing his body there like that, that made him interested in the human form.”

A frigid walk

Killip’s photos have an austere beauty to them — such as the image of a man nicknamed “Cookie” purposefully walking through a snowstorm. But the stories behind them can be quite humorous.

“Cookie was one of the people I was very friendly with,” Killip says. “It was a Sunday morning and his horse, Creamy, had just won a trotting race against guys from town. He’d won a £1,000. The race takes place very early so the police aren’t around. Then we go to the pub — at half past 7 in the morning — and the drinks are on Cookie because he has all of this money.

“Walking back to camp, I knew Cookie had to come back that way,” he adds. “I put the camera on the tripod and I’m swaying quite a bit because I’m drunk. But I knew exactly when I was going to take the picture of him. He didn’t lift his head. I took that one picture, just one frame.”

Punk rock

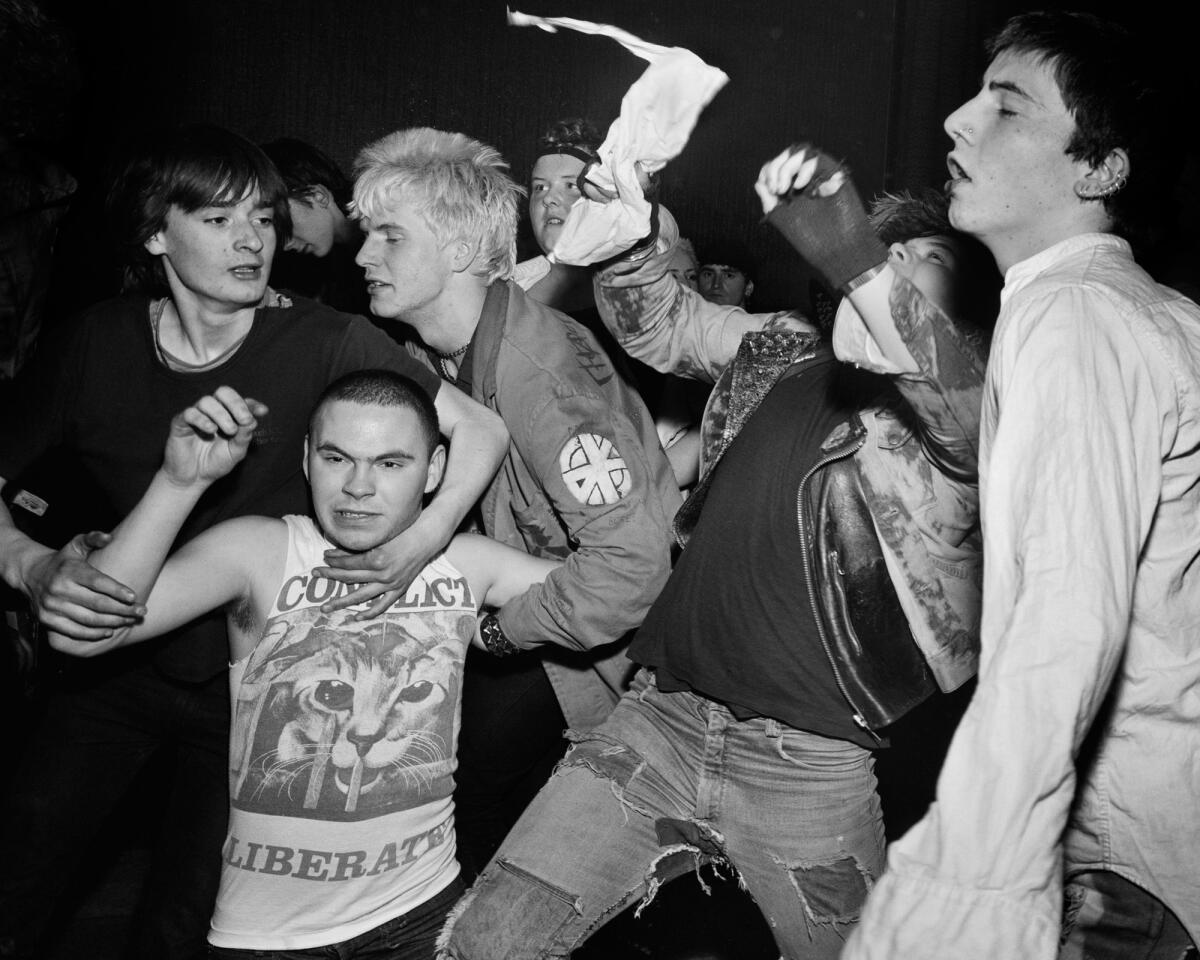

As part of his documentation, Killip caught punk’s second wave in the ’80s. In the picture “Dance, Gateshead” from 1986, he captures a group of kids in frenetic mid-mosh.

“[The club] was located in a former police social club,” he recalls of the space. “It was in town, but the buildings around it had been demolished, so it felt very isolated. Most of the kids were unemployed and this place was very cheap. They charged only like a dollar to go in and they were committed to the local bands and bands from northern England. It’s punk revival — anarcho-punk.

“I went there quite a few times and nobody ever asked me who I was,” he adds with a laugh. “They were all about 18 to about 25 or 26. I was 40. And I would wear the same gray suit and white T-shirt and I carried the big camera with the flash — and no one thought to question my presence. They must have thought I was interesting or an idiot.”

Reverent ritual

“Now Then” is rife with poignant images — perhaps none more so than the photograph of a young boy named Simon being taken out to sea by boat in the wake of his father’s drowning death.

“That was in Skinningrove,” says Killip. “It was a fishing village and it was very difficult to gain access to photograph there. Simon’s father had drowned in an incident at sea. They had this ritual where they came out and took Simon out to sea so that he wouldn’t become fearful of it. It’s very formal. He’s dressed very formally. I was on the boat and nobody spoke.”

A sense of purpose

Killip says that Lynemouth, where the sea-coalers worked, was a “tough place, but it wasn’t an unhappy place.”

“There was lots of energy and lots of fun,” he adds. “There was rivalry and enthusiasms and passions. People were not despairing. It was a very complex community and with a great sense of purpose, which was: get the coal and make money. And I’ve always been interested in places that had purpose.”

He captures this in an image of a young girl named Helen, who plays on a couch that has been left on the beach. “She was the second youngest of Brian and Rosie’s children,” he says. “She had very good movement, always moving and dancing. She is a grown woman now with teenagers.”

“Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante”

Where: Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood, Los Angeles

When: Through Aug. 13

Info: getty.edu

ALSO

Why Star Montana wants you to really see Boyle Heights through her stark and stirring portraits

Dennis Hopper's 'Lost Album' is an intimate photo diary of the ground-breaking 1960s

The last (porn) picture shows: Once dotted with dozens of adult cinemas, L.A. now has only two

Datebook: Photos of adult babies, race and the public figure, and weaving Brazil's landscape

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.