Will Brexit spell bust for architecture?

- Share via

In an interview on the eve of the Brexit vote in 2016, Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas predicted a future of “pea soup and a complete absence of coffee” if the referendum passed and Great Britain withdrew from the European Union. For the European sophisticate, long a part-time London resident, Brexit would mean “Little England” all over again — a small-minded, prim and grim place without espresso. Koolhaas said the European Union “modernized the English mentality,” helping the country find “a way of being English, or being continental and English.”

The referendum did pass, and now as the March 29 deadline for leaving the European Union approaches, the country finds itself paralyzed, unable to decide which kind of Brexit, or a no-Brexit deal altogether. Much has been written about the hundreds of thousands of jobs that could be lost in Brexit-related factory closings, but less noted have been the dire consequences for creative industries, including architecture.

Just like manufacturing, architecture is dependent on international trade. British architects export their services, bringing back work and revenues, while a net influx of foreign architects fills offices: A fifth of the profession nationwide is foreign, and in London, a third, according to British architect Piers Taylor. Norman Foster, who heads Foster + Partners, more than 1,000 architects strong, said, “My practice absolutely depends on talent, and much of that talent is foreign.”

With the deadline approaching, blood pressure rising and a sense of national urgency setting in, architects have been sending open letters of alarm to newspapers and politicians at an accelerating pace. “The priority now is to stop us crashing out of the EU with no deal at all,” wrote Adrian Bull and Alan Bishop to the London Times. The two architects called for another referendum, the so-called “people’s vote.” “The only feasible way to do this is by asking the people whether they still want to leave the EU.”

“Dear Prime Minister,” began an open letter to Theresa May by Taylor, a TV personality and founder of the Bath firm Invisible Studio Architects. Sent to the Times and signed by dozens of architects, including Britain’s most famous — Foster, Richard Rogers and David Chipperfield — the letter continued: “Architecture is an international industry where cooperation across borders is critical to the success of our practices. ... We believe there is no good Brexit.”

The letters all tell a tale of future financial loss, since architecture is directly tied to the construction sector: A decline in imports will cause upward pressure on the price of materials, with a decrease in construction and demand for architects. A smaller market and drop in the gross domestic product will weaken the economy, weakening practices. If Brexit happens, British firms will have to pay increased taxes on their fees for work in the European Union, further decreasing the work volume because of increased costs. British architects will no longer have access to European competitions, a source of commissions for large and small publicly funded projects across Europe. Each year competitions throughout the EU’s 28 nations enable young European firms to establish themselves.

Anticipating the Brexit vote before her death in 2016, the celebrated British architect Zaha Hadid, a Pritzker Prize winner, said in a TV documentary that winning European competitions basically established her practice as a viable business.

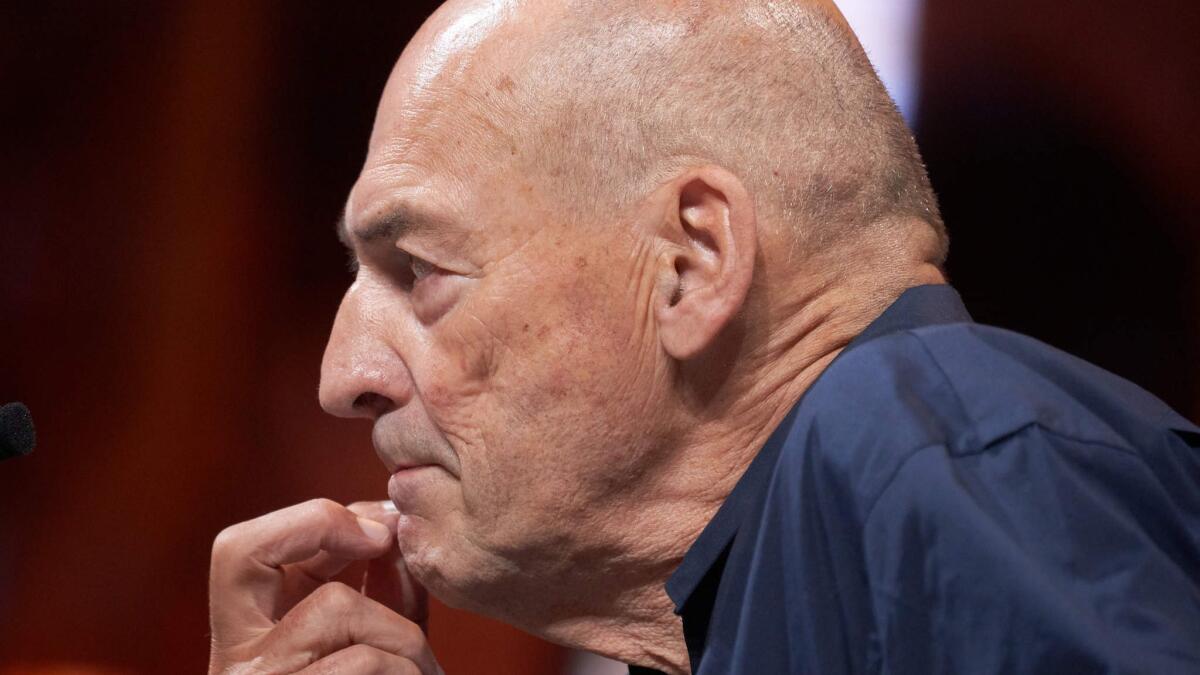

But Chipperfield, an architect active internationally, especially in Berlin, emphasized the qualitative rather than quantitative results of withdrawal from the EU, and said he wasn’t just talking “romantic drivel.” Service industries are especially important, he wrote to the Architects’ Journal, a leading trade publication, since “manufacturing is no longer the base of our wealth, and ... we depend increasingly on our creative abilities.” Creative industries trade in knowledge, he said, and handicapping them through isolation cuts off their oxygen, “suffocating them with our little island mentality.” Diversity breeds cross-fertilization of ideas and skills.

Chipperfield has emerged as architecture’s Churchill in the letter-writing campaign, as he has waged an eloquent, diplomatic campaign of letters to the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Guardian, among others. Like other “remainers” who mainly argue staying in the EU in economic terms, Chipperfield does acknowledge the economic advantages of remaining, but he points out that commercial criteria and the myopia of money have crowded out the philosophical and political debate.

Instead, he argues holistically about the cultural necessity of staying. “The European Union is a political, social and cultural project,” he wrote to the Architects’ Journal. Beyond finance, politics and raw materials, the EU trades in ideas. “We can profit from each other not only in fiscal but in social and intellectual terms.” He links the free movement of ideas to the free movement of people within a larger European cultural community that shares a common history: “The Anglo-Saxon, Germanic, and Latin cultures in close proximity is the extraordinary fortune of Europe.” The English Channel is no longer a barrier from the Continent. It is no longer really just English.

The immigration at the root of the Brexit vote is not a disadvantage for the architects writing the letters, but a cultural and economic gain, as it brings skill, energy and knowledge into the profession. In 2017, Chipperfield wrote that the threat of evicting EU nationals as a negotiating chip was not worthy of a “civilized society,” and the filters admitting new arrivals were unduly restrictive: “The definition of skilled workers excludes almost all of those who are here to work in our industry.”

The industry has already experienced an alarming attrition that is weakening the profession as a workforce. Since the 2016 vote, the country’s architecture Registration Board documented a 42% drop, a record. There were 132,000 fewer EU nationals in summer 2018 than in the same quarter a year before. In addition, with an erosion in workload confidence and the investment climate, large offices are considering staffing cuts over the next three months. None is growing.

To be sure, not all British architects object to Brexit. Hadid’s partner, Patrik Schumacher, favors the deregulation that breaking with Brussels would bring, though he has also opened a branch in Berlin as a workaround. Many British architects have opened offices in Dublin, where they can conduct an Anglo-Saxon practice without being excluded from work on the Continent should Brexit proceed.

As for Prime Minister May’s response to the letter? Tory MP Robin Walker wrote, “As the Migration Advisory Committee have pointed out, ending free movement is not incompatible with a welcoming approach to migration.” Walker’s reassurances were not very reassuring, however. Taylor told the Architects’ Journal: “It completely misunderstands the way the industry works. Clearly they have consulted no one within the industry.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.