What to see in L.A. galleries: street-art ethos, a mesmerizing digital canvas, wild tapestries

- Share via

Sometimes artists make the best curators. And sometimes galleries organize better exhibitions than museums.

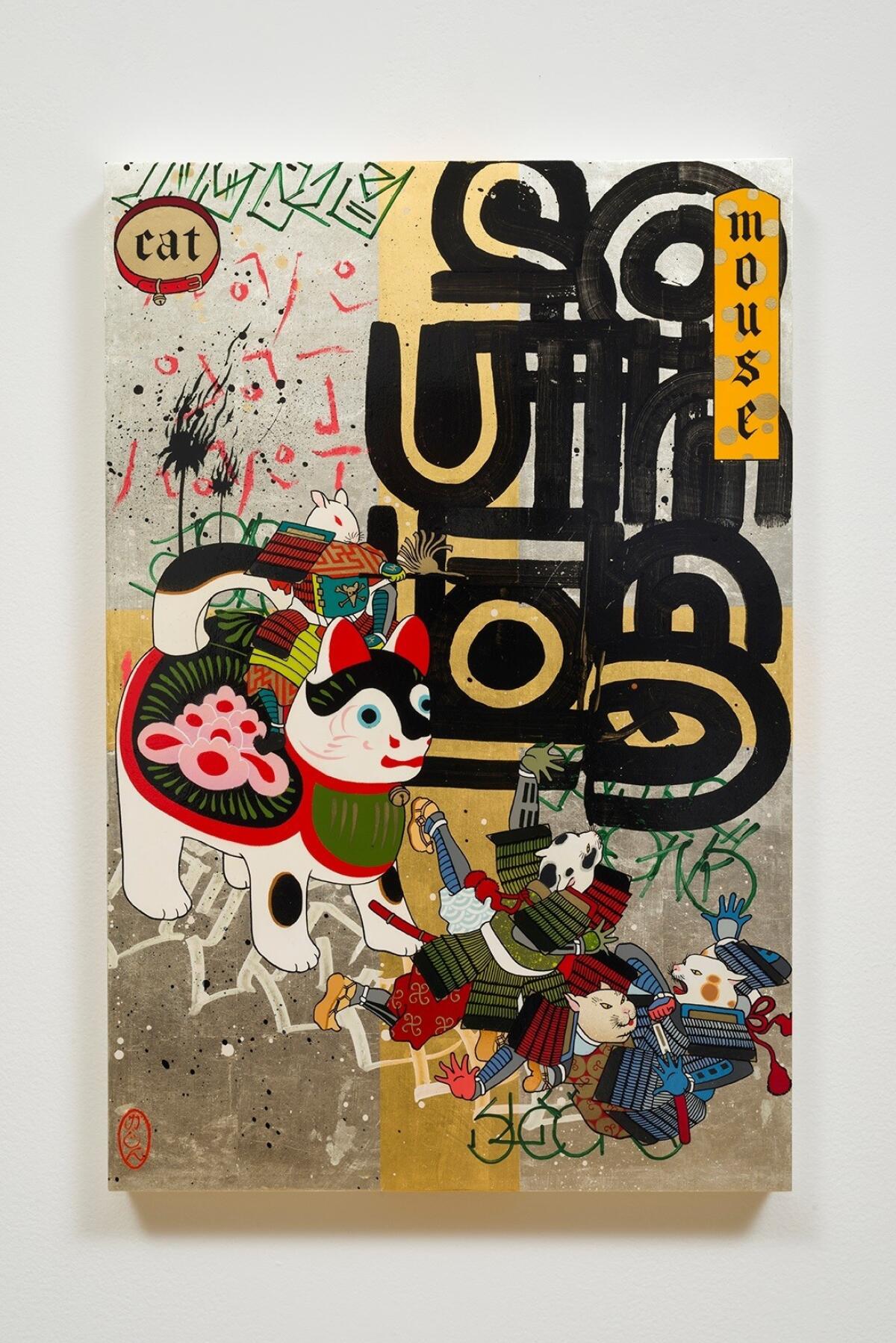

Both happen with “Roll Call: 11 Artists From Los Angeles” at L.A. Louver. Organized by Gajin Fujita, the exhibition reprises “Art in the Streets,” an overblown extravaganza that the Museum of Contemporary Art organized in 2011. In that half-baked sprawl, the art all but disappeared into City Walk-style displays and social events.

In contrast, “Roll Call” sticks to the basics: 35 works by 11 guys. Their paintings are potent. So are their sculptures. An enlightening balance between individual identity and group dynamics is struck.

Each artist has enough room to strut his signature stuff against an illuminating backdrop of his 10 compatriots. The quasi-symphonic whole is a pleasure to get lost in. It also suggests that friendship forms a solid foundation on which an exhibition can be built.

All but one of its artists live in Los Angeles. (Alex Kizu, known as Defer, lives in Hawaii.) Fujita, Jesse Simon and Defer attended junior high at Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies together. Along with David Cavazos (Big Sleeps), Jose Reza (Prime) and Slick, they were members of the graffiti crew K2S. Chaz Bojorquez has long been a mentor to most of the artists in “Roll Call,” and Fabian Debora, Ricardo Estrada, Patrick Martinez and Retna represent a new generation of L.A. artists.

Think of the works in “Roll Call” as friends. They do not look alike. But they get on with one another, often splendidly, always intimately and sometimes contentiously. The texture and resonance of a time and a place are palpable. The same goes for the beliefs and convictions that can be seen in these well-crafted works, where style and pride are worth fighting for.

Homemade cartoons, coded languages, recycled surfboards, futuristic Realism, revisionist histories, cultural mash ups, haunting memento mori and loaded abstractions come in all shapes and sizes. Diversity rules.

That’s just another way of saying that individuality matters. Independence follows hot on its heels, along with the freedom to pursue one’s dreams and ideals. That’s as American as art — and life — can be.

L.A. Louver, 45 N. Venice Blvd., Venice. Through Jan. 14; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 822-4955, www.lalouver.com

Jennifer Steinkamp inaugurates the main space of Acme’s new location in Frogtown with “Still-Life.”

The computer-generated animation is a doozy. Projected onto a movie-screen-size wall (so that the image’s perimeter exactly matches that of the wall), the L.A. artist’s virtuoso display of computer wizardry transforms the darkened chamber into a trip both heady and pleasurable. As fun to experience as it is fascinating to contemplate, her mesmerizing work puts a feminist spin on a great Southern California tradition: art so smart that it doesn’t have to wear its brains on its sleeve.

The solid wall appears to dissolve as Steinkamp makes it seem as if we’re staring off into deep space. That illusion is radical. Rather than bashing through the so-called fourth wall of theater to aggressively occupy the same space that viewers do, “Still-Life” opens onto infinity. The silent nothingness of the void forms the background of Steinkamp’s existential meditation on time’s passage and life’s transience.

In the foreground, supersized fruits, blossoms and sprigs from female fruit-bearing plants bounce around the picture plane. Their colors are luscious. Their contours crisp. And they have been rendered so that there is no way to mistake them for the real thing.

Wonderfully unnatural, Steinkamp’s apples, oranges, pears, plums and peaches resemble the offspring of an old-fashioned slot machine’s whirling symbols and a galaxy on the fritz. Playfully apocalyptic, they move in the manner of lethargic atoms.

Every 50 seconds or so, the image freezes.

Then, all of the fruits, flowers and leaves reverse course, traveling back the way they came.

The paths made by Steinkamp’s gravity-defying objects recall gorgeously woven lace, its delicate shapes even more beautiful in four dimensions. The repetition is soothing. It generates serenity.

As accessible as a screensaver, “Still-Life” is a Light and Space installation for the digital age. Terrifically unpretentious, it leaves visitors with big questions about everything. That’s daunting and inspiring.

Acme, 2939 Denby Ave., Los Angeles. Through Jan. 7; closed Sundays and Mondays. (323) 857-5942, www.acmelosangeles.com

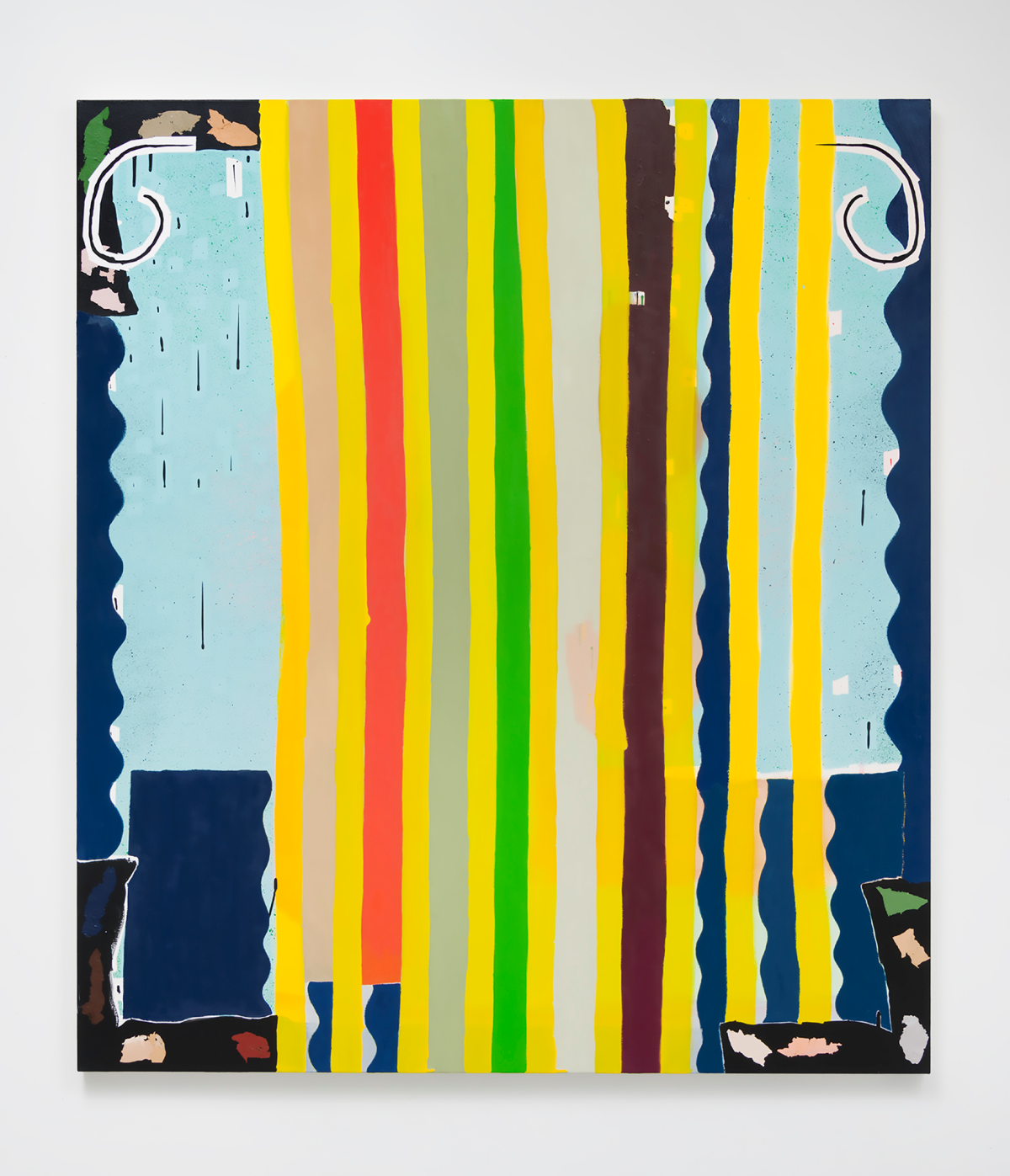

Allison Miller’s rock-solid paintings in “Screen Jaw Door Arch Prism Corner Bed” greet visitors to the Pit and the Pit II with the kind of confidence — natural and unpretentious — that makes you want to get to know them and perhaps become friends.

There’s a rugged loveliness to the L.A. painter’s seven abstract compositions, each of which is made up of simple shapes, unfussy smudges and wayward doodles. All come in colors that can be plucked from any midsize box of crayons.

The sense that Miller’s canvases have a past — with a fair share of hardship, frustration and failure — is palpable. You can glimpse it in the ghostly shadows that haunt the laboriously reworked surfaces of her abstractions, where stray textures roam and partially painted-over sections bespeak decisions that didn’t work.

But more vital are the pleasures her compositions take — and give — in the present.

Those pleasures are multiform. Some come in the form of single drips, which Miller had covered with tape to protect them from subsequent applications of spray paint, oil sticks and acrylic. Others are fastidiously eccentric, like patterns disrupted just for the fun of it or drips of paint dripped atop other drips, forming rainbow rivulets.

Heightening a visitor’s attentiveness to otherwise incidental details, Miller reveals a capacity to transform the nooks and crannies of a composition into unexpected wonders. Seeming to come out of nowhere, these wild delights are all the more potent for it.

Such disruptive magic wallops your body the moment you open the door of the Pit II and see “Bed,” a two-panel painting that covers all but a sliver of the back wall. In one fell swoop, Miller tips the scales to favor not only painting, but all that is possible in art’s nooks and crannies. With her as a guide, that’s a great place to be.

The Pit and the Pit II, 918 Ruberta Ave., Glendale. Through Dec. 31; closed Mondays and Tuesdays. (916) 849-2126, www.the-pit.la

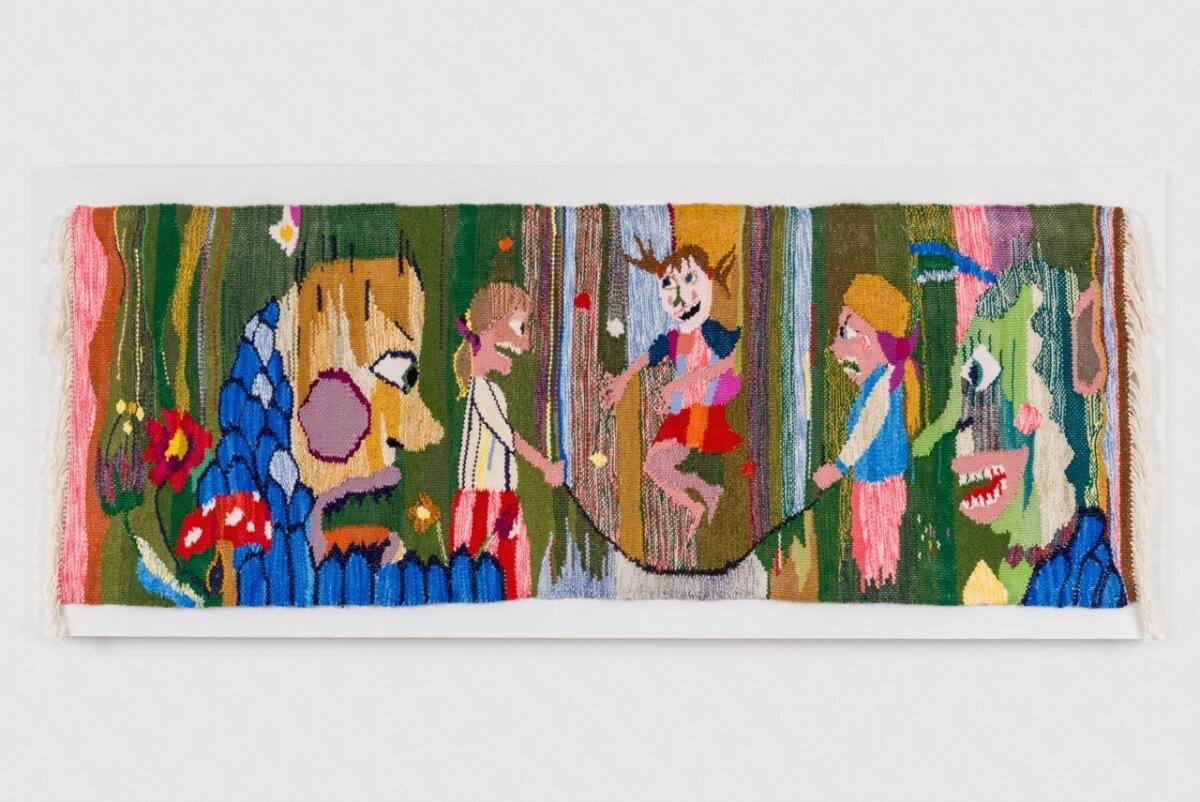

The soul-gripping honesty of children takes startling shape in Christina Forrer’s hand-woven tapestries at Grice Bench.

Although it’s common to think of kids as innocents, it’s less naive to try to see the world through their eyes, unencumbered by the hypocrisy of adult mores and manners.

Each of the Switzerland-born, Los Angeles-based artist’s nine tapestries is a tour de force of formal, pictorial and narrative inventiveness. Forrer uses a loom in the same way that Miles Davis used a trumpet — to blast impossibly original improvisations into the world, where their blunt beauty brings us in touch with some of life’s deepest mysteries.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Forrer’s art starts in her mind’s eye, where stark portraits of simple people and common creatures drift into focus. Using watercolors and color pencils, she sketches these figures on small scraps of paper. Then she enlarges them to become the patterns that guide her work on the loom.

That’s where the magic happens. Using wool, cotton, linen, silk and rayon — in a rainbow of snazzy colors — Forrer weaves labor-intensive renditions of her little pictures. The warp and weft of the thread requires all-or-nothing decisions. This makes for harsh contours, crude shapes and brutal color shifts. The resulting compositions — of kids skipping rope, a couple screaming at each other, an unhappy sasquatch and pair of purple-skinned professors — capture the awkward authenticity of real life.

If the Brothers Grimm were alive, I could see them commissioning Forrer to illustrate their next collection of folk tales. Artisanal technology and post-apocalyptic predicaments have never looked better than they do in Forrer’s richly textured hallucinations.

Grice Bench, 915 Mateo St., Los Angeles. Through Dec. 17; closed Sundays and Mondays. (213) 488-1805, www.gricebench.com

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Thrilling new exhibition shows modern Mexican art is bigger than murals

Martin Luther broke Europe in two, and Albrecht Dürer painted it back together

Go to LACMA for John McLaughlin, possibly the most important postwar artist you don't know

UPDATES:

4:55 p.m. This article has been updated to clarify the background of specific artists in “Roll Call.”

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.