Critic’s Notebook: Antidote for a generation obsessed with screens and constant stimulus: slow, quiet music

- Share via

There were very few empty seats at Monday Evening Concerts, but Israeli composer Chaya Czernowin recommended that those along the sides of Zipper Concert Hall fill up the few empty spots in the middle. She described “Hidden,” her mysterious 45-minute score for string quartet and electronics, as a moving landscape for the ears, which turn into eyes. The center of such a musical Cinerama is where you get the full immersive experience.

Coincidentally, the next night across the street at REDCAT, we were once again instructed to fill the center seats. In this case, though, it was because the theater was sold out and, like on an airplane, filling the center first would make boarding easier for a program of works by Alvin Lucier. The 87-year-old surveyor happens to be renowned as a pioneering architect of sonic room consciousness. A big attraction here was his performance of his classic 1969 “I Am Sitting in Room,” a poignant recitation in which his voice interacts with the sonic properties of the space he occupies.

Yes, space is absolutely the place. The first really good thing to be said about these demanding concerts — which required near meditation on slow, mainly quiet scores with very slight changes — was that they did an excellent job of undermining stereotypes of an antsy new generation addicted to constant stimulus and screens.

SPRING PREVIEW: Critic’s picks of the most promising concerts of the season ahead »

Although there was little crossover between the audiences in the halls, in both cases young outnumbered old by a substantial margin. The audiences were attentive and intent. I didn’t hear a single cough either night. It was obvious the enticement was to have an experience that was new, intense, challenging and not possible any other way. Not even vinyl will do it.

On the other hand, putting too much emphasis on a space can be a very fussy business. Ears may become eyes, but eyes influence ears. So does temperature and smell and touch and leg room and the psychic, physical and aural presence of others. All can enhance, but also distract.

At Monday Evening Concerts, the rational for pairing Schumann’s Piano Quintet, written 172 years before Czernowin’s “Hidden,” was on the fanciful side: the thought of husband and wife. Schumann’s wife, Clara, also was a composer, as is Czernowin’s husband, Steven Kazuo Takasugi. Introducing it all was a three-minute video of a master class with the French pianist Alfred Cortot from probably around 1960 looking and seeming ever the ancient Romantic mystic.

The program notes made the point of Schumann’s capacity to give transcendence to the funeral march in the second movement, which the ad hoc ensemble led by violinist Movses Pogossian managed convincingly. But this was otherwise conventional chamber music played the conventional way in a conventional concert hall, whereas Czernowin wanted something more.

She is a composer who operates around the fringes of sound. The job of the string quartet, here the impressive JACK, is to trick the ears into thinking what is acoustic is electronic. Meanwhile the electronic soundscape tends to make little sonic effects much bigger and thus add to the confusion.

Czernowin said in her introduction that she was after the intensity of being, of finding movement in stillness, joy in sadness and, a little less happily, sadness in joy. A lot of that was the sensation of being in nature, the electronics often evoking atmospheric effects, such as wind and rain and swarms of locusts. Some drama you couldn’t put your finger on. When the electronic sounds moved around the hall, I don’t think it really mattered where you were. I was center left for what that’s worth. The lighting was dark and also dramatic.

But if the room itself matters, little things, stuff nobody thinks about, can make big differences in perception. The JACK used iPads for scores, which is now commonplace among young performers. In a darkened hall, the devices produced a not ineffective glow; however the first violinist’s Bluetooth foot pedal had a blinking light that kept a beat, as if trying to put “Hidden” on life support.

Interestingly, Czernowin and Lucier occupy nearby academic space in the Northeast. She’s at Harvard, and he’s a longtime fixture at Wesleyan, Lucier’s lab for his psycho-acoustical experiments. He too has a striking new ensemble, Ever Present Orchestra, to do his obsessive bidding and which was making its West Coast debut.

The long first half of the Tuesday REDCAT program included pieces written since 2012, and the first, “Ricochet Lady,” seemed a test as to whether you would be up for a night of Lucier. Trevor Saint mechanically repeated short patterns at great speed and at considerable volume (speed and loudness being an exception for Lucier) on a solo glockenspiel, causing acoustical phenomena of ringing and beating. It went on for a long time, and the audience appeared to find it exciting. I, though, began to fear the “Ricochet Lady” was attempting to rewire my brain.

There was no such sense of weaponizing sound in the quiet, drone-based pieces — “Braid,” “Two Circles,” “Semicircle” and the new “EPO 5” — that followed for differing ensembles that included saxophones, electric guitars, saxophones, violins, piano and percussion. These tend to operate on the effects of slight mathematically determined changes of pitch on harmony. Very funny things happen but at a snail’s pace, and they require exceptional concentration on the part of the performers and the understanding patience of the listeners. There were impressive quantities of both.

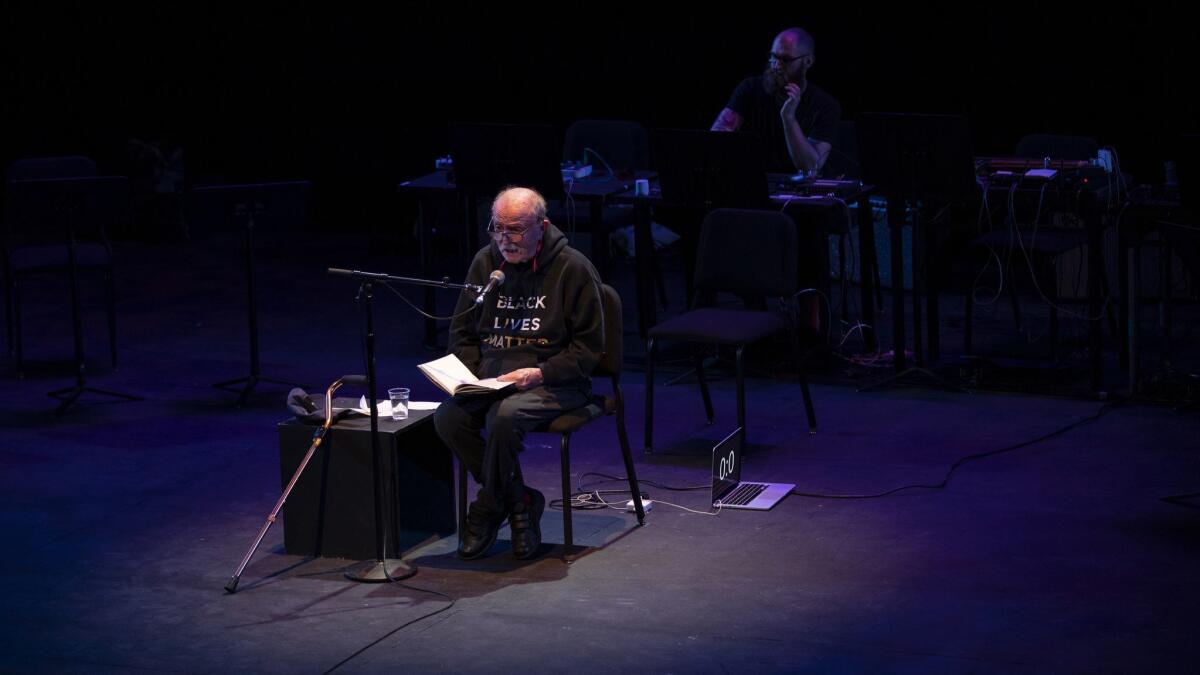

For “I Am Sitting in a Room,” Lucier, who was wearing a Black Lives Matter hoodie, sat in a chair and read a line of text noting that it would be recorded and repeated over and over (for about 25 minutes in this performance) electronically absorbing the room’s acoustics until his voice was turned into smoothed-out electronic sounds.

There is undeniable, if slightly perverse, fascination in hearing Lucier’s voice be absorbed by the room. But there is also something quite disturbing about this. It sounds as though the composer, who remains motionless and expressionless in his chair throughout, is falling deeper and deeper into a cistern until he is lost. You do, though, get a full realization of how much environment matters too.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.