Review: Is ‘The Trial of Anne Opie Wehrer’ even opera? Why nearly 50 years later it stands apart

- Share via

With “Hopscotch” last fall, opera roamed to parts of downtown and Boyle Heights the art form had never ventured, its audiences escorted in safe environments of limousines. Sunday evening the downtown opera scene was limo-less and less sheltered at 356 Mission. The gallery, named for its street address, is hidden away on a dark, former industrial street along the deserted eastern side of the Los Angeles River.

Barely two miles from the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion (where Los Angeles Opera happened to have a matinee performance of Puccini’s “Madame Butterfly” Sunday), 356 Mission presented Robert Ashley’s “The Trial of Anne Opie Wehrer and Unknown Accomplices for Crimes Against Humanity,” an operatic, cultural, socioeconomic, generational, art world and gritty urban underworld away from the Music Center on its hill.

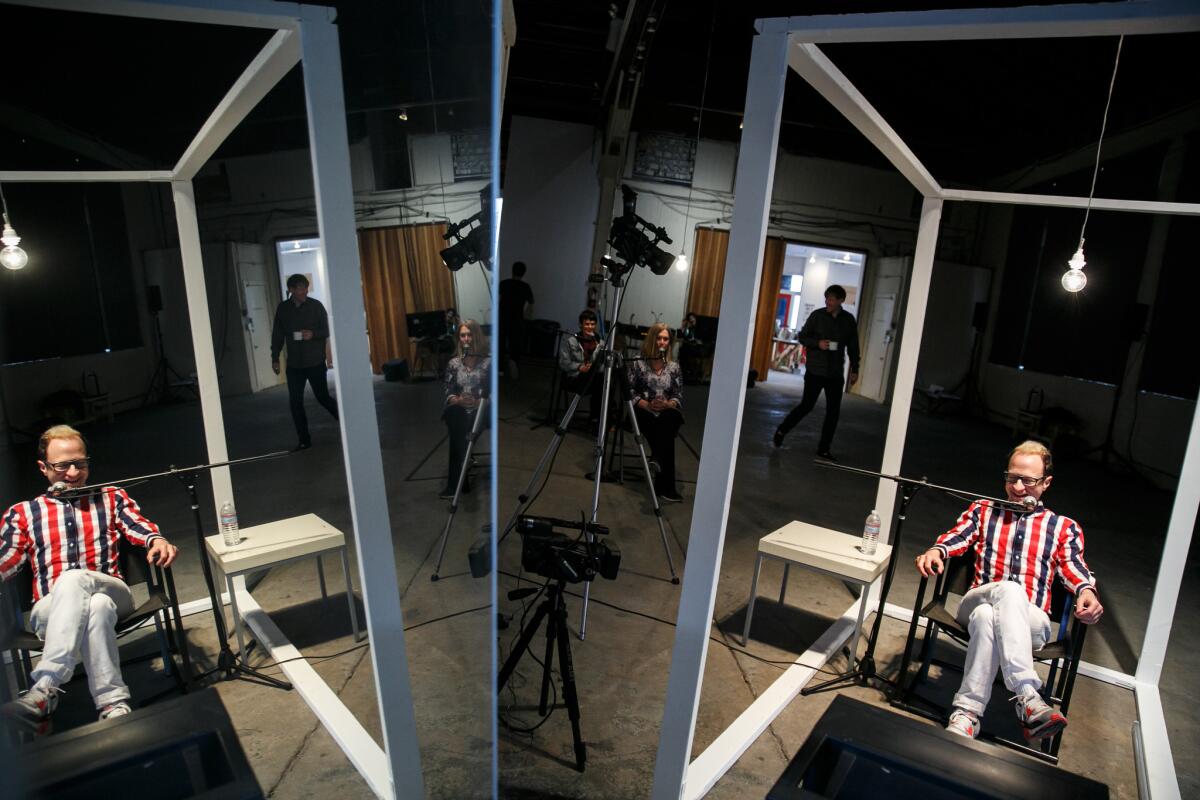

Wayne Koestenbaum, right, jokes with fellow cast members during a rehearsal for “The Trial of Anne Opie Wehrer and Unknown Accomplices For Crimes Against Humanity.”

Unlike “Hopscotch,” which received international attention from the opera press, there have been more than a few who have called “Anne Opie Wehrer” and her crimes against humanity a crime against opera. Is it even opera?

Ashley categorized it as electronic music theater for the premiere in 1969 at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, but he later said he wouldn’t disapprove of calling it opera, even if there was no music per se. The composer, in his sing-song speaking voice, was heard off stage interrogating Anne Opie Wehrer. She sat onstage, her back to the audience, answering startlingly intrusive questions about her personal habits and sexuality. Two pairs of men and women acted as surrogates, cross-examining, answering, interrupting.

No one, Ashley included, had the slightest idea that this would presage a revolution in American opera. The piece was created as a final extravaganza of the ONCE Festival, an annual series founded by Ashley and other young University of Michigan composers who made Ann Arbor in the 1960s a central hub of the American avant-garde. Anne Opie Wehrer was a patron of the festival and known to be quite the talker. The festival’s name came from the fact that pieces often challenging the definition of music were expected to be heard only once.

After “The Trial,” members of the ONCE Group, which put on the festivals, dispersed and came to have a considerable influence on American music. Among them were Roger Reynolds, who went to UC San Diego (where he has remained), and Gordon Mumma, who joined the Merce Cunningham Dance Company.

Ashley spent most of the ‘70s at Mills College in Oakland, continuing to explore novel ways of using the voice (especially his own marvelously sonorous one), electronics, video and stream-of-conscious hyper-narrative, all elements he was to later use in a magnificent series of highly distinctive operas written up to his death in New York in 2014.

The 356 Mission performance of “The Trial” is the production that Alex Waterman directed at the Whitney Museum’s 2014 Biennial in New York. Forty years earlier, Ashley had proposed that the Whitney present it as “living sculpture” and the museum finally got around to it, as a memorial to the composer a month after his death.

At 356 Mission, Wayne Koestenbaum, whose “A Novel of Thank You and Other Paintings” opened at the gallery Saturday, was one of the performers. Ashley’s voice was heard on tape asking the 100 questions. Mary Farley as Wehrer was remarkably composed in her feisty, spontaneous responses. The 90-minute performance was also accompanied by ONCE Festival slides of photographs and newspaper clippings.

Jibz Cameron, left, Kendra Sullivan and Wayne Koestenbaum rehearse their lines for “The Trial of Anne Opie Wehrer and Unknown Accomplices For Crimes Against Humanity.”

The questions themselves could be banal or sophisticated, but Ashley delivered them as music, and that musicality made each unexpected and delightful. Farley was asked about her childhood, her hygiene, her silver patterns, the most famous people with whom she had eaten breakfast, her thoughts on adultery.

Her answers led into strange realms — snoring, gross public flossing, grosser liquefied corpses. Relationships became a preoccupation, and her best line may have been that it’s fun to begin a relationship but more fun to end it.

“The Trial” becomes particularly operatic when the interruptions and answers happen at once creating a complex counterpoint, the speakers needing to be like improvising jazz musicians ever aware of pacing, rhythm, texture and timbre.

No one here could match the special musicality of Ashley’s voice. Still, speech was no longer speech but something more lyrical. Questions weren’t questions but invitations to response. Response was thinking in rhythm. Everything said/spoken/intoned invited more of the same.

Compared with Ashley’s later operas, “The Trial” is rudimentary, and its original notoriety was for its frankness. Many in Ann Arbor found it insulting and were glad to be rid of the ONCE Group. The headline of a review shown on the screen was “ONCE Festival Is Just Plain Dull.”

“The Trial” can still be a trial for the squirmish. A few walked out Sunday, but most of the crowd of mostly young people from the art world sat on folding chairs riveted. Rudimentary or not, they couldn’t have ever heard anything quite like it, because there is nothing quite like it.

And in retrospect, we can now see that opera has never been the same after it.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.