At 85, choreographer Rudy Perez is still inspired by the rhythms of everyday life

“When I put things together, unconsciously, it comes from my lifetime experience up to that moment,” Rudy Perez says.

- Share via

Choreographer Rudy Perez may be 85 and legally blind, but when he strolls along the sidewalks near Hollywood and Vine on a recent afternoon, his vision is crystal clear.

Gripping his cane, the pioneer of 1960s postmodern dance takes slow, deliberate steps, feeling for potholes and curb edges with his toes, as if this were one of his performances.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

He stops by a construction site, an uproar of drills sputtering, metal clanking, trucks beeping. Then Perez, who lives nearby, turns his ear to the site, squints under his fitted white baseball cap and smiles, contentedly. What does he imagine? A symphony.

“Wow, they’re doing a beautiful job,” he says, enjoying the cacophony. More than three decades in L.A. hasn’t diluted his heavy Bronx accent. “It’s wonderful, it’s amazing. Everything is so thought out, so accurate and clear and precise,” he says of the noise. “It’s like a performance piece.”

Perez has long found inspiration in pedestrian sounds, the rhythms of everyday life. His work juxtaposes seemingly simple bodywork with unlikely audio sources, including construction noise, melancholic prayer or even the clink and sputter of Julia Child cooking asparagus in his 1966 piece “Bang Bang.” He’s known for spare, precise movements — one outstretched arm aiming for the ceiling, a jagged bend or tilt — but with his quiet moves, Perez has had an enormous influence on the trajectory of Los Angeles dance. After studying with Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham in the ‘50s, Perez blossomed in New York’s avant garde ‘60s dance scene. He brought his innovative and interpretive abstract expressionism to L.A. in ‘78, igniting the nascent scene locally.

“He came to L.A. as a major artist, a choreographic genius known for making his own rules,” says choreographer Lula Washington, who cites Perez as an influence. “There was nobody here doing that type of experimentation then. He allowed other people to see the possibilities.”

On Nov. 7, UC Irvine will present the choreographer a lifetime achievement award during “The Art of Performance in Irvine: A Tribute to Rudy Perez.” As part of the evening, the Rudy Perez Performance Ensemble will debut work that he choreographed for the event, “Slate in Three Parts.” Despite Perez’s age and impaired vision due to glaucoma and macular degeneration, he still works with the ensemble every Sunday at the Westside School of Ballet, where he’s been teaching for more than 30 years. The new three-piece performance is both in line with Perez’s minimalist style and a departure, in that “everything is forever changing,” he says. “That’s what keeps it alive.”

I never wanted to be a famous dancer or choreographer, it just turned out that way.

— Choreographer Rudy Perez

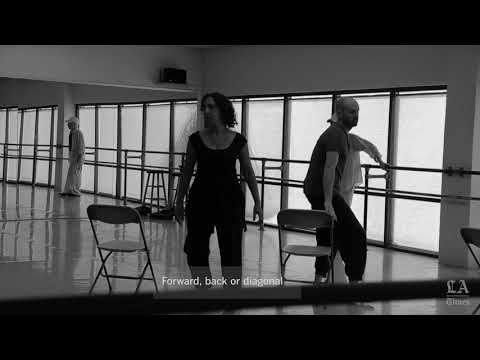

A recent rehearsal is deceptively low key, largely about sound, intuition and well-oiled collaboration. Of Perez’s five dancers in the ensemble, three have been with him for 11, 25 and 29 years — rare in today’s world of project-to-project pick-up companies.

The dancers orbit around one another in silence, performing austere moves dense with emotion. In one section, they repeatedly lower themselves into chairs; in another, they pound their fists against a wall in unison. But there’s a cumulative athleticism to their seemingly easy movements. When they break, the dancers are winded and dappled with sweat.

“Let’s try it to music now,” Perez says, his back to the room.

What sounds like Hindu chanting starts up.

“Listen! Listen to the music,” Perez urges. He paces the length of the room, his hand sliding along the ballet barre and eyes peeled to the floor. The dancers raise their arms, as if in a military salute.

“Reach, reach,” Perez instructs, turning toward them. He scratches at the ceiling, gritting his teeth and snarling his face as if imitating a lion. “It should be a struggle, a struggle. Come on, get those arms up there. Up, up, up, up, up.”

Rudy Perez brings us into a day of rehearsal in L.A., offering insight into what makes movement work.

Choreographing is a struggle for Perez. He misses being able to read facial expressions. But with enough light, he says, he can see basic shapes and shadows. Familiarity with the studio space and his dancers helps.

He also leans on his ears to create. Most days are spent in his apartment, with radios in the bedroom and living room tuned to KUSC-FM (91.5) and KPCC-FM (89.3) from the moment he wakes until bedtime. The omnipresent mix of classical music, news chatter and everyday ambient sound melds with long-ago memory to spark ideas for movement. “But nothing is planned, it all comes from the unconscious,” he says. He also takes inspiration from current dance performances. When friends and students stop by with groceries or to pick him up for doctor appointments, they relay details of what they’ve seen.

“When I put things together, unconsciously, it comes from my lifetime experience up to that moment,” he says. “Then ultimately, it turns out to be about something for someone, certainly for me. But I don’t expect for it to be the same for the audience.”

Just don’t ask Perez what a piece is about. Of the new “Slate,” he says: “It’s very much how I feel about what’s going on in the world.”

“Which is what, exactly?” he’s asked.

“I’m not gonna say. I’m very abstract. Once it becomes narrative, it’s all over. Let the audience decide what it’s about.”

Then: “Come on, they don’t ask Merce this stuff.”

Dance has always been a part of Perez’s life. The son of Peruvian and Puerto Rican immigrants, he grew up in East Harlem and the Bronx doing the cha-cha and the samba at family gatherings, where he’d improvise on the dance floor.

But struggle has also been a through line. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was 7; the disease landed him in the hospital, where he stayed, mostly bedridden, until he was 10.

“I think a lot of the pain you see in some of my work that’s very sort of contained comes from that experience, from being in the hospital and hardly having any visitors,” he says. “It’s all very suppressed, but it’s there in my work.”

When he returned home, he had the responsibility of caring for three younger brothers while his dad worked as a merchant marine.

Perez took his first dance class — modern — at the New Dance Group in 1951 at the urging of a friend. That led to studies with Graham and Cunningham as well as with Mary Anthony, among others. He took menial jobs by day — waiter, messenger, usher, Bloomingdale’s stock boy — while studying dance at night. As a Latino who didn’t come from privilege, however, Perez couldn’t fathom that the mostly white professional dance establishment had a place for him.

“I was never thinking where it would take me. I was just living in the moment, balancing my life. It could’ve been a hobby,” he says. “I never wanted to be a famous dancer or choreographer, it just turned out that way.”

Perez says he took unbridled passion from Graham and intellectual rigor from Cunningham, but he found his own voice in the early ‘60s at the experimental collective Judson Dance Theater alongside Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, Lucinda Childs and Trisha Brown. He pushed boundaries, staging site-specific works in public parking lots and gyms before it was trendy to do so.

His first choreographed work, “Take Your Alligator With You” in 1963, was a spoof on magazine modeling poses that debuted at Judson. His first solo piece, “Countdown” in 1966, consisted of Perez moving sparingly in a chair while smoking a cigarette. Audiences may have been befuddled by his unconventional “dance,” he says, but over time he became a critics’ darling. For his first evening of dance solos, at the YWCA Clark Center for the Performing Arts in the late ‘60s, only four people showed up: all reviewers, including ones from the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, as he recalls.

“It was devastating,” Perez says of looking out into the audience. “Except that once I realized who was there, everything opened up. The reviews were unbelievable.”

New York had been good to Perez, but he had longed to leave since childhood, when he’d sit on the edge of the East River and watch the tugboats go by.

A yearlong substitute teaching stint at UCLA brought Perez west in ’78. He was struck by the open space, the palm trees and the potential for site-specific work.

I’ve always been told, ‘Grow old gracefully’ -- and I’m good at that.

— Choreographer Rudy Perez

“There were so many wonderful spaces to do outdoor pieces — streets, office buildings, courtyards, that weren’t being used,” he says. “In L.A., I felt freer, I was able to go beyond. I wanted to get away from the emphasis on dance and work more with theater and natural movement.”

The L.A. contemporary dance scene then was a geographically scattered but vibrant world. There was longtime contemporary dance fixture Bella Lewitzky, the Dance Kaleidoscope festival, experimental companies and spaces like Dance LA, Santa Monica’s the House and Eyes Wide Open Dance Theatre. But Perez’s innovation sparked what dance critic Lewis Segal calls “a real firestorm in L.A.”

“Teaching it and choreographing from it, he made a difference,” Segal says. “The glamour and the achievement of that New York scene — all of the sudden, here it was, bam! It encouraged people to really go with their instincts, to go for broke.”

Perez formed his dance company shortly after arriving — a priority, along with learning to drive at age 49 — and he went on to stage works all over the city, from small experimental spaces like Highways in Venice to major venues like Royce Hall at UCLA. He also created work for the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival.

To date, he’s created more than 50 works in about as many years and has taught all over L.A., including at the USC School of Dramatic Arts and the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts. His archives are part of the USC Libraries’ Special Collections.

In December, the Colburn School will restage Perez’s 1983 “Cheap Imitation.” Former Perez ensemble dancer and Colburn teacher Tamsin Carlson will direct the piece, which she says “is very much of the ‘80s. Rudy was influenced by David Hockney. The dancers wear aqua and sunglasses and leg warmers. It has a pulse and patterns.”

Though Perez says the newer “Slate” is the last work he will choreograph, partly due to his physical limitations, he hopes to restage it at the Colburn in 2016.

“Once the work is created, the next challenge is to find a different space to present it in. I enjoy that,” he says. “The piece is always ongoing.”

The UC Irvine tribute adds to accolades that have included a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, L.A.’s the Music Center/Bilingual Foundation’s !Viva Los Artistas! Performing Arts Award and honorary doctorates from the Otis College of Art and Design in L.A. and the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. As part of the evening, Perez’s ensemble will perform an excerpt from “Shifts,” which premiered at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena in 2003.

“He’s the most important living choreographer in Los Angeles,” says Sasha Anawalt, director of USC Annenberg’s master’s program in arts journalism. “That he’s still going is amazing.”

Perez takes it in stride.

“I’ve been very fortunate,” he says. “I’ve always been told, ‘Grow old gracefully’ — and I’m good at that. At this stage of my life, sure, it’s hard, but I’m striving for excellence. I wanna go out with a flash.”

ALSO:

‘The Art of Falling’ stage is big enough for Second City improv and Hubbard Street dance

Ira Glass’ ‘Three Acts, Two Dancers, One Radio Host’ makes a whimsical mix

‘Hamilton’s’ revolutionary power is in its hip-hop musical numbers

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.