Regal to let deaf moviegoers see what they’ve been missing

- Share via

Raymond Smith Jr. has been trying for nearly two decades to make the movie industry listen to the needs of the deaf and hard of hearing.

This month, the senior executive at Regal Entertainment Group will come closer to his goal.

His company, the nation’s largest theater chain, will have nearly 6,000 theater screens equipped with closed-captioning glasses that could transform the theatrical experience for millions of deaf and hard-of-hearing patrons who have shunned going to the cinema because previous aids were too clunky or embarrassing to use.

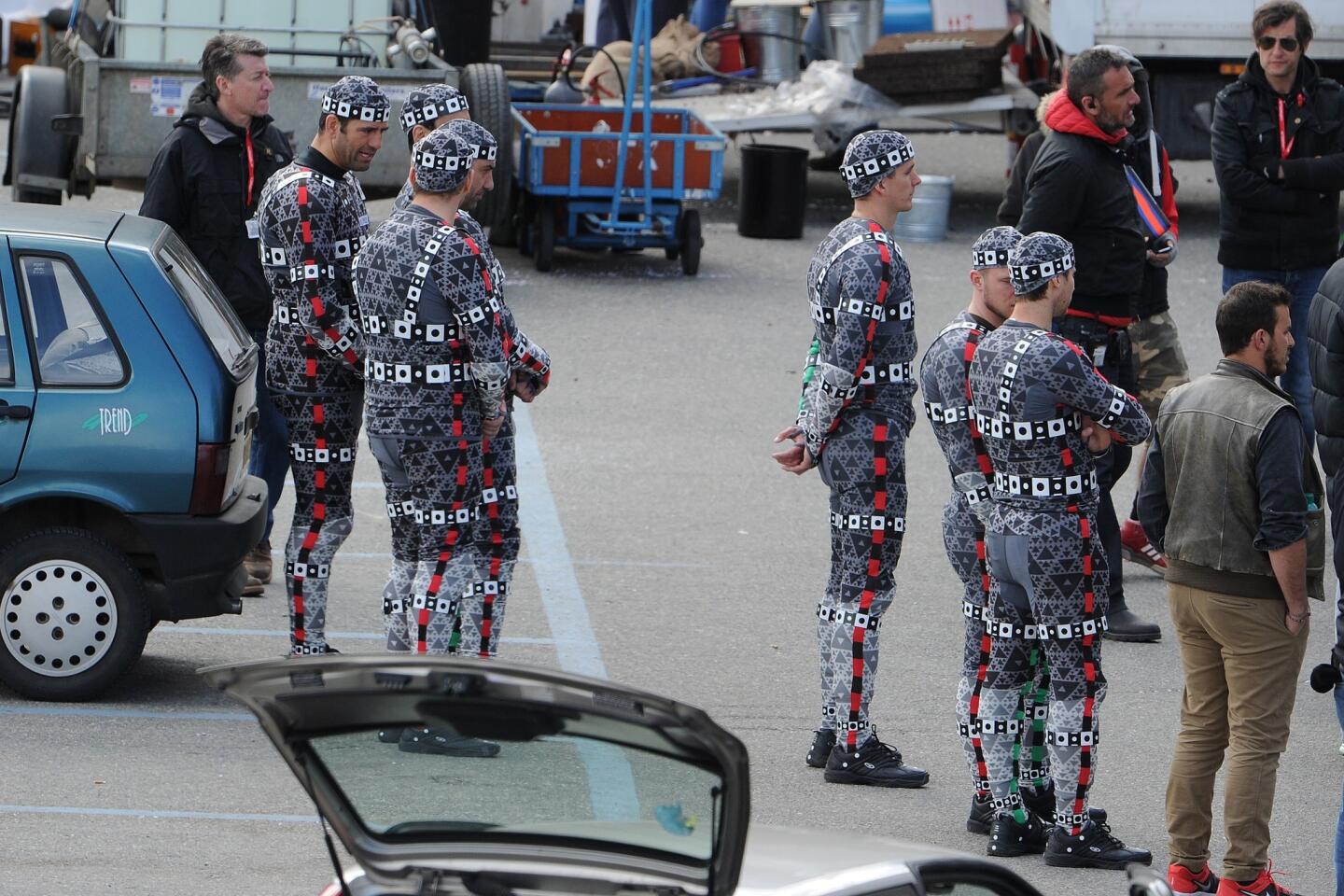

PHOTOS: Hollywood Backlot moments

The Knoxville, Tenn., chain has invested more than $10 million in the glasses, which were developed by Sony Electronics Inc. Resembling thick sunglasses, the device uses holographic technology to project closed-caption text that appears inside the lenses, synchronized with the dialogue on the screen.

The system also includes headphones connected to a wireless receiver, with separate audio channels, which play dialogue or allow visually impaired users to listen to a narration track of the film.

For Smith, the investment is the culmination of a personal journey. His son Ryan is deaf. The 23-year-old college student and aspiring screenwriter played an important role in Regal’s decision to order the glasses last year.

“He was our guinea pig,” said Smith, counsel and chief administrative officer for Regal. “Every time a new prototype came out, he gave me immediate feedback.”

Until now, movie options for the deaf and hearing impaired have been limited. Initially, studios released few movies with captions. Exhibitors screened them infrequently, or at odd hours. When cinemas introduced closed-caption devices mounted in seats many users found them clunky, conspicuous or incompatible with their hearing aids.

The new Sony glasses — which cost theater owners $1,750 (including a receiver and transmitter) but are free to customers — don’t have such problems, advocates say.

ON LOCATION: Where the cameras roll

“They don’t stand out or make you look different, and people don’t have to dip their heads to look at a screen and miss what’s going on,’’ said Nanci Linke-Ellis, a partner in Captionfish, a search engine for captioned movies and trailers. “The majority of people I know have not gone to the movies in 35 years because the technology wasn’t available. This is a game changer.”

Since introducing its glasses last spring, Sony has sold more than 6,000 pairs to Regal, Carmike Cinemas Inc. and Alamo Drafthouse, among other chains.

“We see these glasses as a way to fill a need in the deaf community,” said Susie Beiersdorf, vice president of digital cinema sales for Sony Electronics.

It’s also good business. Exhibitors such as Regal are eager to find new ways to draw customers at a time when theatrical attendance in the North America has slackened. AMC Theatres and Cinemark USA Inc., the second- and third-largest chains, respectively, offer different closed-captioning devices that are less expensive.

More than 38 million Americans live with some sort of hearing disability, and only 34% of them go to a movie theater at least once a year. That compares with 72% of Americans overall who went to the movies at least once in the last year, according to industry surveys.

Major theater chains have also faced pressure from the Justice Department and advocacy groups to improve access to their auditoriums.

Regal and Cinemark have faced lawsuits in the past from disability rights advocates alleging they were violating the Americans With Disabilities Act. New Jersey’s attorney general sued Regal in 2004, demanding the chain install a rear-window system in which text is reflected from an LED screen at the back of the theater. Regal balked, maintaining the systems were unpopular, and the suit was later settled.

Smith says Regal’s actions were not motivated by either the lawsuits or pressure from the Justice Department, which in 2010 said it was a considering a rule that 50% of movie screens offer captioning and video description services.

“Did litigation force us into this? No,” Smith said. “We decided well before the litigation what we were going to accomplish and we did it.”

In fact, Smith’s commitment to the cause sprang from his own experiences raising a deaf child. Smith says his son loved movies as a young boy but was often disappointed when he couldn’t join his peers to see the latest release because the film print was not captioned. He also recalls how awkward Ryan felt watching a movie for the first time with the help of a rear-window screen.

“He was very uncomfortable,” Smith said. “It became apparent that there had to be a better way to do this.”

Smith became an advocate for more close-captioned movies. He arranged for periodic movie screenings with students from the Tennessee School for the Deaf at a Regal theater in Knoxville. And when new captioning devices became available, Smith organized meetings with groups including the National Assn. for the Deaf to solicit their feedback.

He also invited his son to join him in theaters to test various devices and glasses.

“I would come home and say, ‘We’re going to the movies tonight,’ and he was more than happy to assist me,” Smith said. “If he said to me he didn’t like it, it was a non-starter.”

Ryan Smith did like the Sony glasses, but suggested a few improvements after testing an early prototype, including making them lighter, adjusting the nose pad to make them more comfortable and enlarging the size of the captions.

“I was one of the first people to test the device out before it was put in Regal theaters across the United States,” the younger Smith said. “Knowing that my opinion really mattered because I am a deaf customer, I did my best to give my honest opinion. It was one of the coolest things I’ve ever done.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.