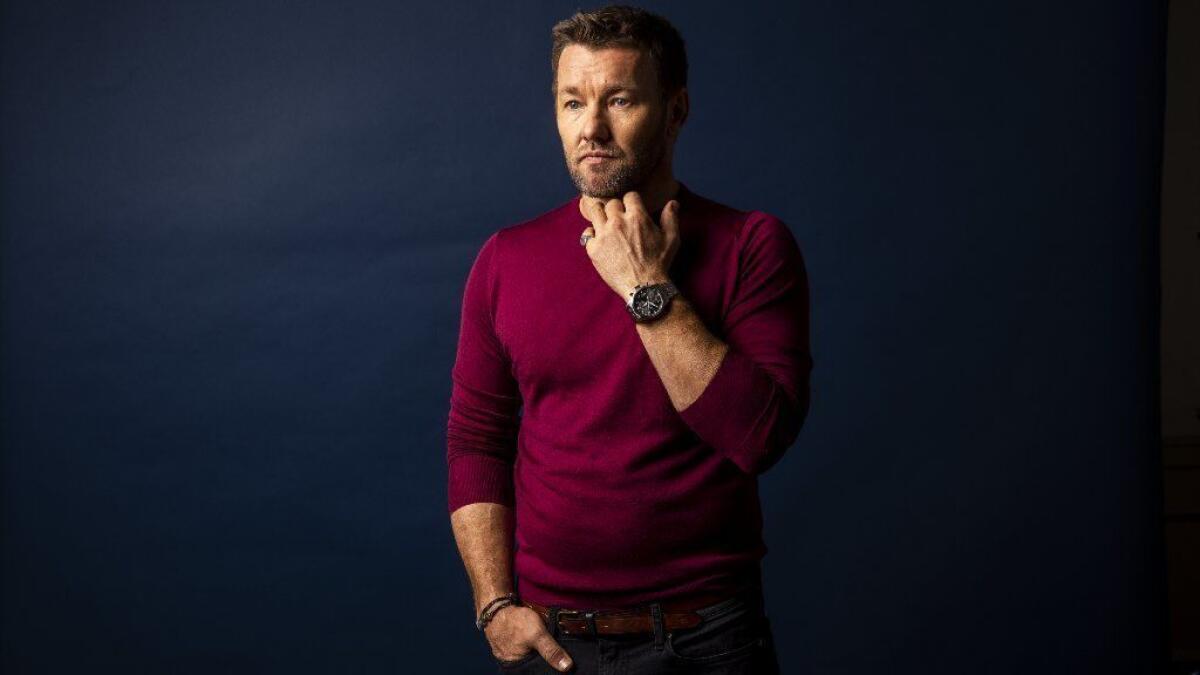

No villains in the gay conversion film ‘Boy Erased,’ just bad decisions, says director Joel Edgerton

- Share via

As if Australian-born actor Joel Edgerton wasn’t busy enough with a career that typically sees him starring or costarring in at least two films a year (a few of which he also wrote), he decided to add feature director to his résumé. It was an auspicious move.

The result, 2015’s “The Gift,” a twisty thriller about an L.A. sales exec whose past comes back to haunt him, proved a hit with both critics and audiences. It also earned Edgerton, who wrote and costarred, a DGA Award nomination for first-time feature film directing.

So what do you do for an encore?

Edgerton, whose many film credits include “Animal Kingdom,” “Zero Dark Thirty,” the 2013 remake of “The Great Gatsby” and “Loving,” had an ace up his sleeve: the book “Boy Erased: A Memoir of Identity, Faith and Family.” Written by Garrard Conley and published in 2016, it was the true story of a young Arkansas man who comes out as gay and is sent by his Baptist minister father and acquiescent mother to a conversion therapy program called Love in Action.

RELATED: Stepping behind the camera is a natural move for some actors »

Edgerton adapted the highly charged story, casting Lucas Hedges as Conley (Jared), Nicole Kidman and Russell Crowe as his parents, and himself as Love in Action’s driven head therapist, Victor Sykes (based on the group’s former executive director, John Smid). The result is a rich and vital work that’s harrowing, heartfelt and, ultimately, hopeful.

Recently, over cappuccino at a West Hollywood hotel, the filmmaker spoke with warmth, candor and enthusiasm about this passion project and its potential to alter perceptions — and misperceptions.

With all the acting roles at your disposal, how did you decide to again devote so much time to writing and directing a film?

It gave me such satisfaction the first time. But, in all honesty, this book got under my skin so much. It chose me, picked me and dragged me along with it. It’s like, “Yeah, I could go and make more money working on three or four movies during that year-and-a-half period of time,” but I never really thought too much about it.

Although “The Gift” is a very different film from “Boy Erased,” both are so effective in ratcheting up tension and creating a sense of mystery. How did you manage those elements here?

I kept coming back to [the concept of] family and realizing that I didn’t want to go too far into suspense world. I felt if I just let the story unfold through Jared’s day-to-day experience that there would be enough suspense, enough tension, because, like him, we wouldn’t know what was coming next … how dark, how dangerous, how threatening any of this might be.

How much did your screenplay deviate from the book?

The biggest addition was putting a little more flesh and bone on the different Love in Action patients, including the creation of Gary [played by pop star Troye Sivan] and Cameron [Britton Sear]. Cameron is an amalgam of other stories that I’ve heard through Love in Action. My mantra was that if we had one shot at telling the story, we had to tell the darkest parts of the results of the practice.

Your character, Sykes, is the “villain” of the piece, whether he means to be or not. It’s a tricky role. How did you approach it?

I just took my lead from meeting John [Smid]. He was so warm, articulate, charismatic; somewhere right between an alpha and a beta male. He was a leader.

Speaking of which, how did you avoid vilifying Jared’s devout parents? They’d be such easy targets, yet there’s a gentleness and dimension to them.

We don’t give anyone a free pass in this movie, but we certainly don’t demonize them. And I actually took my lead from the book. In Garrard’s story, everybody thought they were trying to help him. When you really examine his parents’ decision, that act [sending him to conversion therapy] was born out of a love for him. That was far more complicated than I expected.

There’s clearly a built-in audience for the film. But how do you get people who may need to see it most, say, those with anti-LGBTQ sentiments, to do so?

I don’t know, but I’ll tell you what you can do: Anybody sitting on a fence, you can pull them over to one side. This movie definitely fits in that pocket of having the opportunity to change minds. I think it can really speak to parents who know that conversation about coming out is looming in their household, or it just happened or happened a while ago.

I challenge people to watch the film in order to really look at how somebody else handled that situation in a wrong way but was also willing to reexamine those mistakes. Because even if you have made a mistake — whether it’s sending your kid to conversion therapy or rejection of any other kind — it’s never too late to pick up a phone or knock on a door and just go, “I want to have another conversation.”

FULL COVERAGE: Get the latest on awards season from The Envelope »

More to Read

Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.