How the London Film Festival joined a worldwide push for diversity and inclusion

- Share via

Reporting from London — During the first weekend of the 62nd BFI London Film Festival, 80 women from the industry gathered for a memorable photo. The image, which puts the festival’s artistic director, Tricia Tuttle, and BFI’s chief executive, Amanda Nevill, at the forefront, celebrates the importance of gender diversity in the film industry, both in the U.K. and worldwide.

For Georgia Parris, who stood alongside actresses including Rosamund Pike and Andrea Riseborough, as well as directors, screenwriters and producers from around the world, the photo brought an essential moment of much-needed visibility.

“I started as a volunteer here about 10 years ago,” recounts Parris, whose film “Mari” had its world premiere during this year’s festival, which wrapped up Sunday. “It was about two years later that I saw my first female director. It sounds ridiculous, but I hadn’t seen one in the flesh. It was Joanna Hogg and she was doing a Q&A and I realized, ‘I can’t believe I’ve never seen a female director before.’

“The festival was bringing these women to the forefront and it hit me how important it was to see them. You need to see people to think, ‘Maybe one day I could do that.’ It’s changed my life because now here I am doing it.”

Pike, whose new film “A Private War” played during the Mayor of London’s Gala, saw the photo as a way to remind the industry of the sheer number of women who help tell stories with film. “What the BFI are doing is amazing,” Pike notes. “Tricia said, ‘Look at all this talent we’ve put together here. Look at what we’re all doing in positions that make a difference.’ This time of year, there are always a group of films that the conversation is about. She said, ‘Go out there and see the other films. Start the conversation. You can be in control of the conversation.’ I left feeling very inspired from that brief moment on the steps.”

Female representation was at the heart of this year’s festival lineup, which included 225 feature films and 160 short films from 77 countries. Of all the films screened, 38% came from female directors, including 30% of features, up from 24% last year.

Gender parity was achieved in three of the four festival competition strands, including a 50/50 split in the official competition. These numbers are significant higher than other European festivals. Earlier this year at the Venice Film Festival only one in 21 official competition features was directed by a woman, and three out of 20 were female-directed at Cannes. Still, LFF hasn’t specifically set out quota numbers regarding gender equality.

“We didn’t set ourselves quotas, but we’re always conscious of wanting to go in that direction,” says Tuttle. “We always look for a range of voices. We see the official competition as a microcosm of the festival as a whole. It’s important that to us that [the festival] has a global spread, that is has different approaches to filmmaking and storytelling.

“But also when we got to a point this summer when we realized gender parity was a possibility — and very easy to achieve — that was very exciting to us. That’s the message we want to give: That we find and champion female directors.”

This effort matters to filmmakers, who see festivals as a unique opportunity to showcase their work to larger audiences. Eva Husson brought her film “Girls of the Sun,” which also played at Cannes.

“We lack so much representation onscreen in terms of telling the stories of women that every chance we get to have people come to the movies and get another chance to watch the world is important,” Husson notes. “Every time I come [to a festival] and every time I search out that response it feels [like] so [much] energy coming back to me. I can see directly the result of three years of hard work.”

It was great to see a vibrant, mixed London audience coming to see the film. It felt like exactly what we want the festival to feel like.

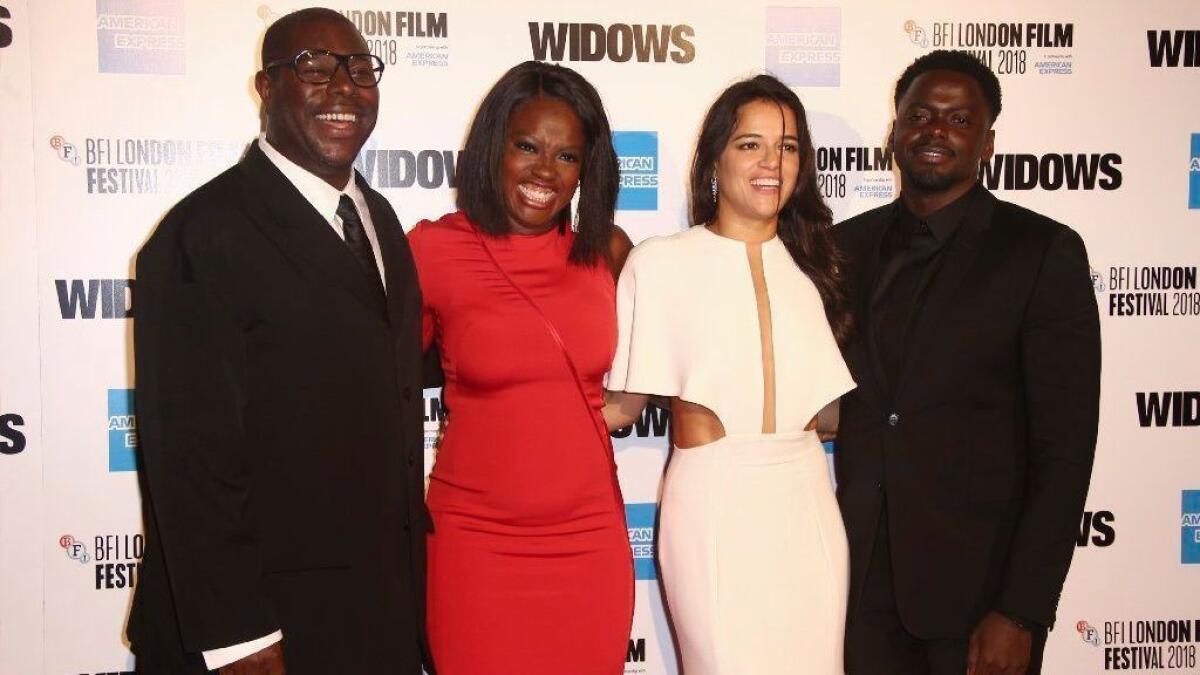

— London Film Festival director Tricia Tuttle on the gala screening of Steve McQueen’s “Widows”

While a large portion of the films in LFF’s lineup this year were created by female directors, many of the male directors also centered their narratives on women. From Luca Guadagnino’s “Suspiria” to Yorgos Lanthimos’ “The Favourite” to Tom Harper’s “Wild Rose,” a majority of the evening galas were films about women.

“Opening with ‘Widows’ from Steve McQueen, a London filmmaker, was particularly great,” Tuttle says. “It’s such a strong story in terms of being female-fronted, and it’s got an incredibly diverse cast. Anecdotally, it was great to see a vibrant, mixed London audience coming to see the film. It felt like exactly what we want the festival to feel like.”

The festival’s organizers have thought extensively about how to attract an audience as diverse as their films. For Tuttle, encouraging broad viewership at the public screenings comes with careful programming.

“You need to create a program that feels inclusive and welcoming and accessible,” she notes. “The best way to do that is provide a range of films so people see themselves reflected in your priorities as a program team. We’ve seen very clear correlations in the past few years when we do measures at the end of the festival. When we have a great year of East Asian cinema, for instance, we over-index on our East Asian audience. We’re really conscious of that.”

The festival is also conscious of its attendees who require accessible screenings. Each year, LFF provides public screenings with English subtitles for those who are hearing impaired and with audio soundtracks for those who are visually impaired. During the industry panels that take place throughout the festival, the organizers also hope to make disability part of the conversation. One specific panel, called “Busting the Bias,” followed up on a panel from last year that addressed disability on- and off-screen.

“We’re engaging with a network of disabled filmmakers at the moment to see where we can grow our collaboration,” says Jennifer Smith, the BFI’s head of inclusion. “Often it [isn’t] discussed within our industry and there is so much to cover in terms of portrayal, in terms of disabled practitioners in the field. We’ve got a really good lineup. It’s been a focal point to talk about disability.”

“There has been a notable shift as last year was very empowering,” notes returning panelist David Proud, a working actor and writer who was born with spina bifida and uses a wheelchair. “I think we all realized that we have a collective voice that has authority and we were all on the same page. This year we are presenting the results of a roundtable that I hope will become a framework of how to engage disabled people in film and TV. If everyone adopts this framework it would be game changing.”

He adds, “The difference with LFF is that the disabled filmmakers almost take over the place. We get to talk about what we want, not to rehash the same dialogue.”

LFF, which splits its films into themed strands alongside the big gala presentations and official competition strands, also spotlights LGBTQ representation with its BFI Flare, which this year included Wanuri Kahiu’s lesbian-centric film “Rafiki,” which was originally banned in its home country of Kenya. Because the festival selections come from so many countries, there is also a sense of genuine racial and cultural diversity.

Screen Talks were presented by filmmakers including Alfonso Cuarón (“Roma”) and Lee Chang-dong (“Burning”), and the festival brought Boots Riley’s Sundance hit “Sorry to Bother You” into the lineup after the director was vocal about the challenges of European distribution for African American films (the film is now being released overseas by Universal).

“We’ve got a very diverse programming team,” Tuttle notes. “The gatekeepers come from all different backgrounds and have a very good gender split. We do a lot of talking about programming choices and how they fit into the shape of what we’ve already selected. What we’re excited about is not just representation, full-stop, but how brilliant these films are and how excited we are to immerse all kinds of audiences in the vibrancy of cinema right now.”

Showcasing African American stories outside the U.S. is particularly important for filmmakers like George Tillman Jr., who brought “The Hate U Give,” about a 16-year-old African American girl who witnesses a white police officer fatally shooting her childhood friend, to the festival ahead of its U.K. release.

“In my entire 20 years making films I’ve only been to London twice,” the director says. “This is the second time — I was here for ‘Notorious,’ which was just a screening, not a film festival. There’s that sense that African American films don’t travel or work nondomestically, so I always think it’s great to be able to share our work outside of the United States.”

Tillman’s film is currently drawing crowds in a nationwide theatrical release in the U.S., and had its world premiere last month at the Toronto International Film Festival. “One of the things I’m most proud of about this film is that it’s been working universally for everyone,” Tillman adds. “I think people react to things that are very authentic. I think 10 years ago or 15 years ago most films were made by white men with white protagonists. After a while you get tired of the same story and the same thing. You’ve got new voices now.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.