Mindy Kaling and Emma Thompson’s crowd-pleasing ‘Late Night’ breaks the ice at Sundance

Writer/producer/star Mindy Kaling and director Nisha Ganatra visit the L.A. Times Studio at Chase Sapphire on Main to discuss their love for Emma Thompson and writing ”Late Night.”

- Share via

Reporting from Park City, Utah — Times film critic Justin Chang is keeping a regular diary over the course of a week at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. He will be writing about the movies he’s seeing, the trends he’s observing and what it all means for an event that officially kicks off the year in new independent cinema.

A busy shooting schedule kept Emma Thompson from attending the Sundance Film Festival premiere of “Late Night,” a smart, crowd-pleasing comedy in which she plays a smart, not-so-crowd-pleasing comedian. The actress was sorely missed, but maybe it was just as well. In the movie, written by and co-starring Mindy Kaling, Thompson tosses off her every line with such acid-tipped aplomb, she might have found herself to be her own toughest act to follow.

In any event, her absence couldn’t help but reinforce the notion that we had just spent almost two hours in a giddy parallel-universe version of Hollywood, one that reflects the biases and blind spots of the industry at large but is at least progressive enough to feature a late-night talk show hosted by a woman. That host is the acerbic, high-minded Katherine Newbury (Thompson), who’s facing sagging ratings and a steady downward slide into pop-cultural irrelevance.

Not long before the network head (a sharp Amy Ryan) informs Katherine that this season will be her last, the host decides it’s time to change things up and finally bring a woman into her all-white, all-male writers’ room. In comes the bright, chipper Molly Patel (Kaling), a chemical plant worker and comedy enthusiast who, being the only female applicant, lands the job. But while she may be a blatant diversity hire (the fact that she’s a woman of color is a bonus), Molly brings with her some strong ideas, an overdeveloped knack for constructive criticism (she used to work in quality assurance) and a willingness to push back against white male privilege.

She has a lot of hurdles — and a lot of initially contemptuous, ultimately endearing colleagues — to overcome. (The fine ensemble cast includes Denis O’Hare, Reid Scott, Max Casella, Paul Walter Hauser and Hugh Dancy.) But Katherine, too, has a lot to learn about compromise in a field that would prefer she dispense with the erudite guests and cram her show with light-hearted sketches and YouTube celebrities. There’s a pleasingly layered quality to the satire in “Late Night,” which targets Katherine’s pop-cultural cluelessness even as it bows before her intelligence, and which allows Molly to be savvy and naive, idealistic and cynical, tough and vulnerable all at once.

Smoothly directed by Nisha Ganatra, “Late Night” at times achieves the dexterous fluidity of a great ’40s workplace comedy, with Thompson in sublimely withering form as a boss lady just a few shades cuddlier than Miranda Priestly. Whether the movie’s portrait of a TV writers’ room meets anyone’s standard of verisimilitude is debatable and possibly beside the point, though I do wish the industry-centric jabs were sharper, and that Katherine’s show actually got better when it was supposed to; the numerous cutaways to audience laughter aren’t always convincing.

Audiences beyond Sundance, however, are likely to give “Late Night” a solid embrace. The morning after the movie’s premiere, news broke that Amazon Studios had purchased U.S. rights for $13 million after an all-night bidding war. That’s an even heftier sum than the $12.5 million it paid here two years ago for “The Big Sick,” a very different movie but a similarly deft weave of effervescent comedy and barbed politics. Not the worst outcome for a movie that, as Kaling noted during the post-screening Q&A, had been something of a gamble, insofar as she had written the screenplay specifically for Thompson.

It’s “the stupidest thing you can do,” Kaling said. “Thankfully, she said yes.” It’s hard not to share in her gratitude.

READ MORE: Justin Chang’s 2019 Sundance Film Festival diary »

‘After the Wedding’ and ‘Native Son,’ two adaptations with a twist

Everything old is almost new again in “After the Wedding” and “Native Son,” two of the first narrative movies I’ve seen here in Park City. Each one is a curious adaptation of well-regarded material — surprisingly faithful in some respects, and just as surprisingly divergent in others. Both pictures have their flaws and their fascinations, especially if you’re familiar with their antecedents.

In Bart Freundlich’s gently tear-streaked family melodrama “After the Wedding,” Julianne Moore and Michelle Williams play Theresa and Isabel, two women brought together by a business opportunity and an unexpectedly tangled history. Theresa, a successful New York entrepreneur, has three children with her sculptor husband, Oscar (Billy Crudup), including a daughter, Grace (Abby Quinn), who is about to tie the knot. Into the celebration comes Isabel, a frowning free spirit seeking a donation for the orphanage she runs in India, unaware that she is about to get much, much more than she bargained for.

The story, with its explosive secrets and tentative stabs at reconciliation, largely mirrors that of Susanne Bier’s 2006 Danish film of the same title, with one crucial change: In that movie, the two leads were men, played by Mads Mikkelsen and Rolf Lassgård. But the more significant difference may have less to do with gender than with form: Bier’s movie, loosely influenced by the aesthetics of the Dogme movement, achieved a jagged immediacy with its jittery handheld cameras. Freundlich’s remake is stately, composed and even glossy by comparison, which makes some of the story’s violently contrived twists seem even more jarring in context.

The remake feels at pains to acknowledge its characters’ privilege, even as it piles on the gorgeous surfaces, the expensive meals and the multimillion-dollar real estate. (The wedding looks as though it cost a fortune.) The trickiest character is Isabel, whose love for India and the children she’s left there is dramatized in blandly touristic fashion, but Williams is extraordinary: Simply by casting a glance or tightening her features, she can make you feel Isabel’s anger, her grief and the weight of demons that have tormented her for years. Well after “After the Wedding” has ended, it’s her presence that haunts you.

Something similar can be said of Ashton Sanders, the mesmerizing 23-year-old actor at the center of “Native Son.” This debut feature from the visual artist Rashid Johnson is the third screen adaptation of Richard Wright’s landmark 1940 novel about Bigger “Big” Thomas, a young black man from Chicago’s South Side whose life of desperate poverty and privation takes a cruelly violent turn.

It is the first adaptation, however, to update its story for the present, a choice that, conceptually, requires both boldness and subtlety. Written by the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, this “Native Son” means to trace a direct line from the systemic injustices and persecutions experienced by African Americans in the 20th century to those they continue to endure in the present. The result is a strangely potent but muddled brew: It’s urban realism with a boldly anachronistic streak, a sly comedy that tilts into tense, brooding tragedy.

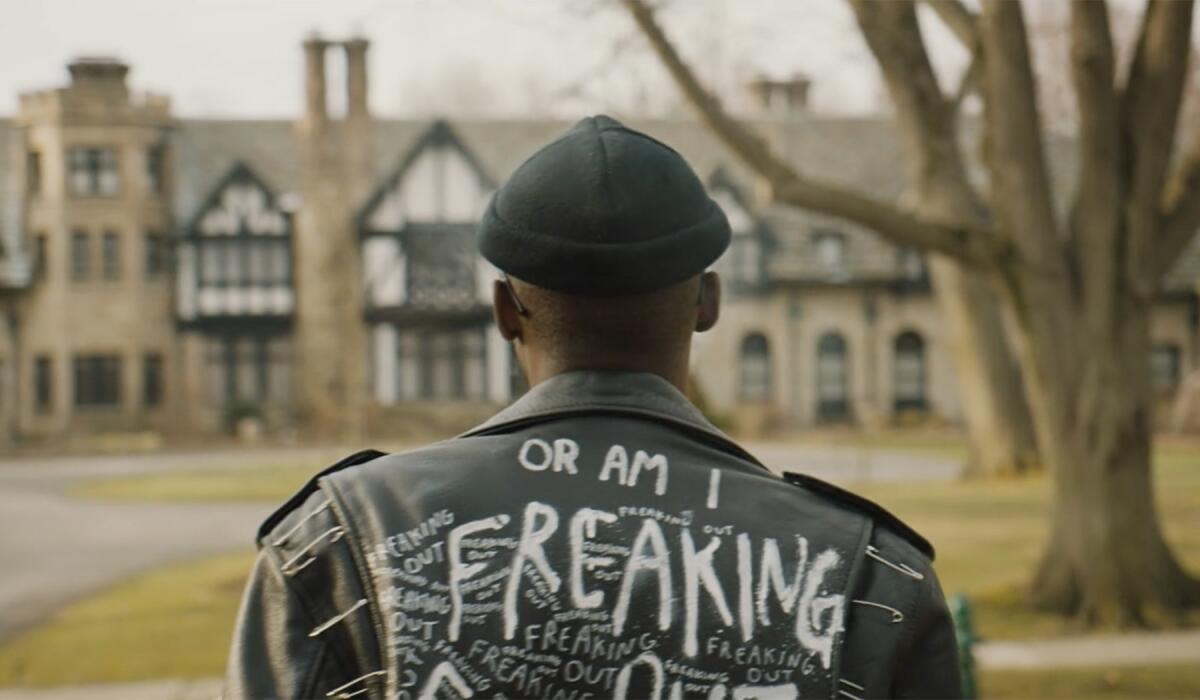

Sanders, so memorable as the teenage Chiron in Barry Jenkins’ “Moonlight,” similarly magnetizes the camera’s gaze as Big, a skeletally thin young man who lives with his mother (Sanaa Lathan) and two sisters in a poor and comically rodent-infested Chicago apartment. Big’s very look is a calculated provocation: dyed-green hair, dark glasses and a black leather jacket with the words “Or Am I Freaking Out” scrawled all over it. His identity, while still slippery and unformed, has clearly been shaped to his detriment by a society where black men are expected to know their place.

An opportunity arises when he gets a job as a chauffeur for the Daltons, a white family living in a tonier part of town, and gets to know their teenage daughter, Mary (Margaret Qualley). Their scenes together — especially on the town, where the reckless, Mary brings Big into her circle of hard-partying friends — are written and played with darkly satirical verve. But after a grisly, intensely harrowing set-piece midway through, the story’s narrative and thematic possibilities feel increasingly limited by its faithfulness to its source material. We know from the outset that tragedy is inescapable, but even still, the movie seems to be narrowing just as it should be getting more expansive.

The largely appreciative reception to “Native Son” got its own twist early in the festival: HBO Films announced that it had acquired the movie from A24, meaning it will air on the premium cable channel and bypass theaters. That’s too bad, insofar as the picture is more than anything a triumph of atmosphere, beautifully framed by the versatile cinematographer Matthew Libatique (a current Oscar nominee for “A Star Is Born”) and moodily scored by Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein. All the more reason to be grateful it played at Sundance, even if we come to this festival hoping to see narratives on the big screen for the first time, not the last.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.