For Ethan Hawke, upending the biopic, and a few other saws with it

- Share via

Reporting from NEW YORK — He’s probably best known as the voluble philosophizer in Richard Linklater movies, the kind of guy who plays himself really well. But the truth is Ethan Hawke contains plenty of range. (“Truth” in that Ethan Hawke, he’s seeking-to-find-it-every-day-kind of way)

The actor has showed he can pull off elevated genre material (“Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead,” “Training Day,” hopefully the upcoming “Magnificent Seven” remake), less elevated genre work (“The Purge”) and topical drama (“Good Kill”). Also, if you’re of a certain Gen-X age, you remember the first time you heard Troy Dyer say “You look like a doily” the way Baby Boomers remember the moon landing or Millennials recall their first Taylor Swift concert.

All of that Hawkeishness comes together with his sidebar material -- his stage work, his authorial efforts (an upcoming graphic novel about the Apache Wars, e.g.) and his directorial pieces, like last year’s sublime documentary “Seymour” An Introduction.” Hawke has long been part of the Hollywood firmament, but with perspective; like his pal Mark Ruffalo, he’s a veteran actor who’s figured out how to get just close enough to the machine.

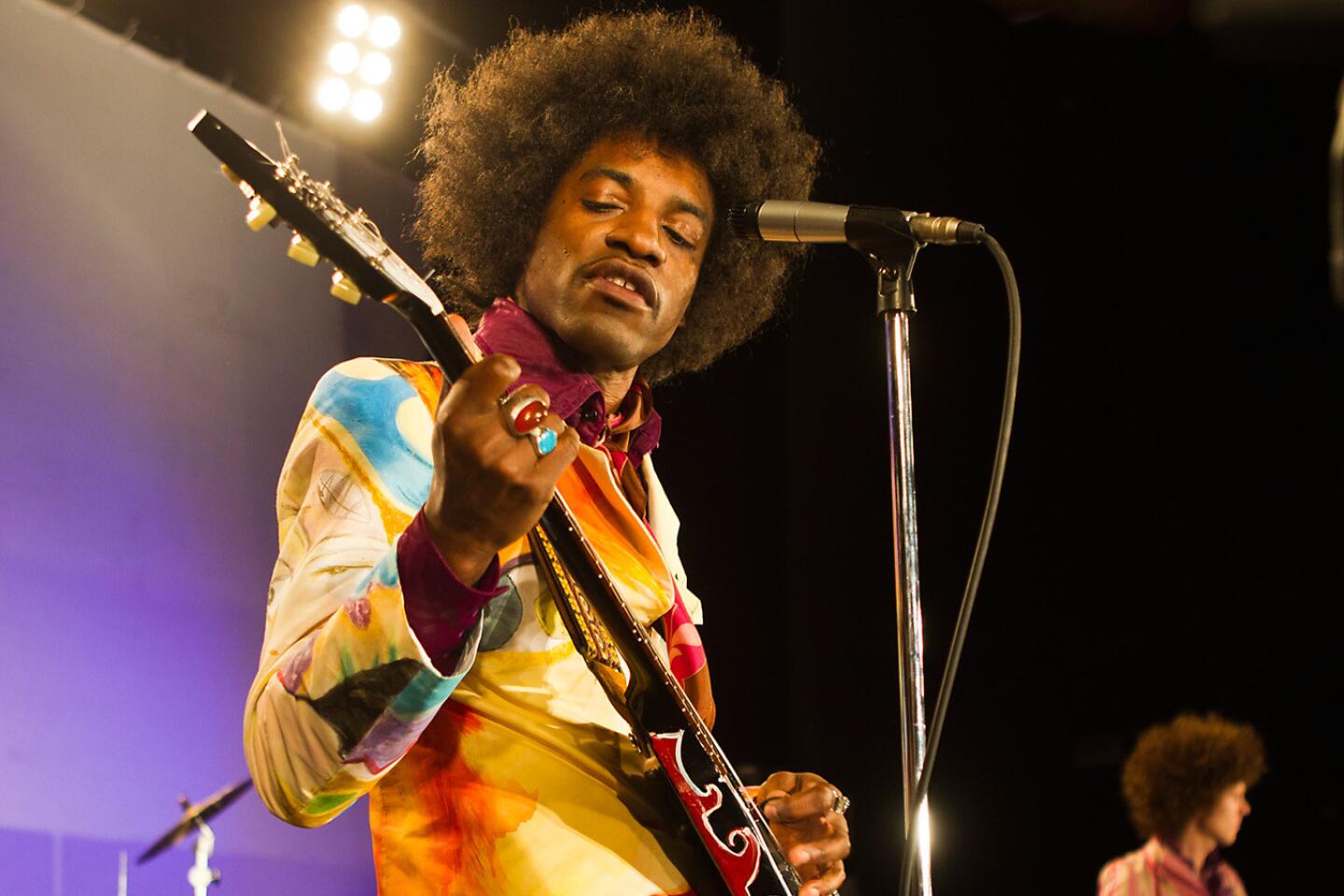

The latest project for Hawke, 45, is the newly released “Born to be Blue.” Hawke stars as the late troubled jazz trumpeter Chet Baker. By tackling Robert Budreau’s film -- the movie opened this past weekend to a solid $16,000 per-screen-average in Los Angeles and New York -- Hawke is adding real-life, fact-based biopic to his resume. Though as viewers quickly realize, this is hardly a traditional biopic, and the film’s first priority is not hard facts.

Over lunch in New York, where Hawke lives with his family, the actor engaged in a freestyle conversation about subjects including politics and jazz -- Trump and trumpeting -- as well as race, superheroes and Philip Seymour Hoffman. These are excerpts from that conversation.

The Times: You’ve just made a movie about a famous 20th-century artist, yet it doesn’t seem to follow the rules of movies about such figures. There’s a film-within-a-film; there are aspects of his life that seem imagined, like a fever dream.

Ethan Hawke: I feel like we live in a great era. There was a time when movies had a historic responsibility. Because they were a version of history. But now you can sit on your phone and Wikipedia comes up and tells you exactly what happened. Movies don’t need to play the role they once did. So I felt a different obligation, one that’s more to jazz than to history. I mean, one of Chet’s friends told me that one of his favorite movies was “Drugstore Cowboy.” How can you make a straight biopic after hearing that?

The Times: I thought the handling of Baker’s heroin addiction was refreshingly non-traditional, too. It seemed to be a portrait of someone for whom that compulsion is less a consequence of fame, as we’ve seen in so many biopics, and more a fact of life that’s always there--something a character just has to manage, or not manage.

Hawke: Drugs are a symptom. We wanted to investigate the cause. We wanted to go in there devoid of judgment. It’s more “What makes this guy tick? How can he personify cool but be so fragile on the inside?” A lot of movies treat addiction as a distinct event. It’s not that. Or it wasn’t for Chet.

The Times: It’s strange that “Born to be Blue” and Don Cheadle’s Miles Davis biopic “Miles Ahead” are coming out the same time. They’re both about jazz legends, and both have very unconventional--some might call it post-factual--takes on their subjects.

Hawke: I ran into Don recently and he told me he wanted a lot of the same things we did. I was telling him someone should program these movies as a double feature. And Miles and Chet also had an interesting relationship, as you see from our film.

The Times: Yes, there’s that great, tense moment when Miles pops up in the movie and dresses Chet down, basically saying to him, you’re all flash and no talent. There’s also a bit of a racial undercurrent to it.

Hawke: Miles and others were certainly irritated with the fact that Chet didn’t invent bebop and yet he’s selling more records imitating those who did. But it’s also a ‘don’t blame Chet’ situation. That’s our culture. White culture has been co-opting black music for a long time. Eminem is a real artist with something to say. But he also does well because it’s a face a lot of white America is more ready to love. It’s unfortunate. But it’s sometimes the reality. It’s changing, but it used to be and sometimes is still the reality.

What I find beautiful in all this is that it’s non-verbal; it goes beyond race. That’s what trumpet is; that’s what music is. A safe haven. Because if you can play it doesn’t matter what color you are. Jazz music did a lot of what rap did later. It works its way into people’s hearts. And it made people see race differently. It’s the tip of the spear, really.

The Times: Where do you think movies and actors fit into that?

Hawke: To me the great example is [“Training Day” and “Magnificent Seven” co-star] Denzel Washington. Because he’s become a movie star by being a world-class dramatic actor--at a time when audiences don’t want drama. Think of how massive those obstacles are. And think of how he overcomes them. White audiences relate to him. He’s not a comedian and he’s not a rapper. He’s a leading man. And we see ourselves in him.

The Times: Except Denzel almost seems like he’s forgotten in terms of race and Hollywood now. He and Will Smith broke these barriers. And now these barriers are up again. The industry has not created, or sought out, the next Denzel.

Hawke: I was in the room the night Denzel won best actor [in 2002]. And it was also the night Halle Berry won. Sidney Poitier was in the house. It felt like Civil Rights history, like the ship was finally sailing. And then you think it’s behind us and realize it’s not behind us. I was talking to Don about how hard it was to get ‘Miles Ahead’ made. People they kept saying black people don’t sell internationally. If that’s true why is the NBA so popular? Why is ‘Creed’ so popular? Cam Newton being a quarterback is still an issue. It’s amazing the way the national dialogue is happening.

The Times: The trajectory seems to be that of one step forward two steps back.

Hawke: This is going to sound left-of-center. But a number of years ago I did ‘The Cherry Orchard’ at [the Brooklyn Academy of Music]. It was the night Obama was elected. And ‘The Cherry Orchard’ is a story about a former serf who’s now buying a farm. So I’m walking through Brooklyn after the show that election night and you could hear the catcalls and howling, you could hear the waves crashing against the walls. The vestige of architecture is gone. Yet we’re not far from Washington Square Park, where black people were hanged not really that long ago.

I keep spinning my wheels trying to figure out what the truth is. I listen to Spike Lee talk about racism; he knows a lot more and he has a lot more to say than I do and I hope he gets to make one movie every year, because he has such an important voice. I don’t understand why there aren’t more movies about minorities of all kinds. I saw [Chloe Zao’s Native American film] ‘Songs My Brothers Taught Me’ and I couldn’t believe there haven’t been more movies about the reservation.

The Times: And yet now you’ve made a movie about a largely African-American form of cultural expression--which is one of the few places black actors can get lead parts in movies--except you made it about a white person. Do you catch any heat for that? Do you personally feel conflicted about it?

Hawke: I’ve thought about this a lot. You know, as I’m doing this graphic novel, [‘Indeh’] about Native Americans. I would think sometimes, as I was working on it, ‘this is not my story to tell.’ Sherman Alexie and many others--it’s their story. They should tell it. But I was interested in the subject. These are wars that involves white people and native people and what it means to be American. And that’s why I felt OK telling it. I’m not stopping anyone else from telling it.

But it’s an interesting dilemma-what’s the line between celebrating and appropriating? People get mad at Clint Eastwood because he made ‘Bird.’ Like, Charlie Parker is not his story to tell. I don’t think he should be stopped from doing that. I think people should never be told what story they can’t make, no matter what color they are. But on the other hand I haven’t had anything taken away from me the way that African-Americans have. So I understand the full riddle of it all.

The Times: Which kind of connects to Oscars So White. You’re in the academy. A lot of people in the academy had mixed feelings about the controversy--they recognized a systemic problem but they felt they were being called racist, which they don’t feel they are. How deep do you think the problem goes? Will anything be solved by all the membership changes?

Hawke: Well, on the Oscars themselves, I think they acquitted themselves nicely during the show this year. I think Chris Rock’s performance lanced a national wound. Comedians say things we can’t say. But obviously the problem goes deeper, to the kinds of movies being made. [Pauses] I just refuse to look at an award show as an arbiter of good taste and quality. It’s an ad for movie industry. We all love to get prizes. [Shoot], that’s why we show up, that’s why we watch. I really don’t think you can look to it for leadership.

The Times: So are there movies that you feel could stem the tide?

Hawke: Well, just one example that’s close to home is ‘Magnificent Seven.’ What we’re trying to do is something very different. It’s placing a black actor in the middle of Dick Cheney’s America. Our goals were more modern. The guy with the great knives isn’t James Coburn; it’s a great Korean actor. It’s not Eli Wallach playing a Mexican. The are Latino actors. And the gunslinger is Denzel Washington, not crazy Yul Brynner. Then there’s Antoine [Fuqua], an African-American director, captaining the whole ship.

It also speaks to issues that are, sadly, still happening. I play a former Rebel soldier who Denzel’s character saves and we become great friends. And we’re shooting in Louisiana, and on talk-radio they’re talking about protesting Confederate flags. This movie is set 150 years ago and it feels like it’s about how we live now.

The Times: That’s a subject that seems of deep interest to you--how we live now. Or how we can live better. It’s certainly something your character in ‘Born to be Blue’ is grappling with. And it was in the fabric of ‘Seymour’--an octogenarian man [piano teacher Seymour Bernstein] saying how it can’t just be about getting good at your art but becoming better as a human.

Hawke: It was perfect kismet. I just finished making ‘Seymour: An Introduction. ‘And then I got this script about Chet. i thought a lot about Seymour as I was making this movie. I’d wake up every morning and as I got dressed I would listen to Chet. And I would often think about the lack of respect with which he treated himself, treated his talent. It’s just pulling up your own roots. I really liked the Amy Winehouse documentary. But thought what ‘Amy’ was showing you was how to kill yourself. And Seymour was showing you how to live.

The Times: Did he see this film?

Hawke: He did the other day. It was really touching. He liked it. I also think he would have something to say to Chet. Chet wore his inability to read music--even after all his success--as a badge of honor. And Seymour would have said ‘No. That’s not enough. Let’s imagine better than you are.’

Ethan Hawke

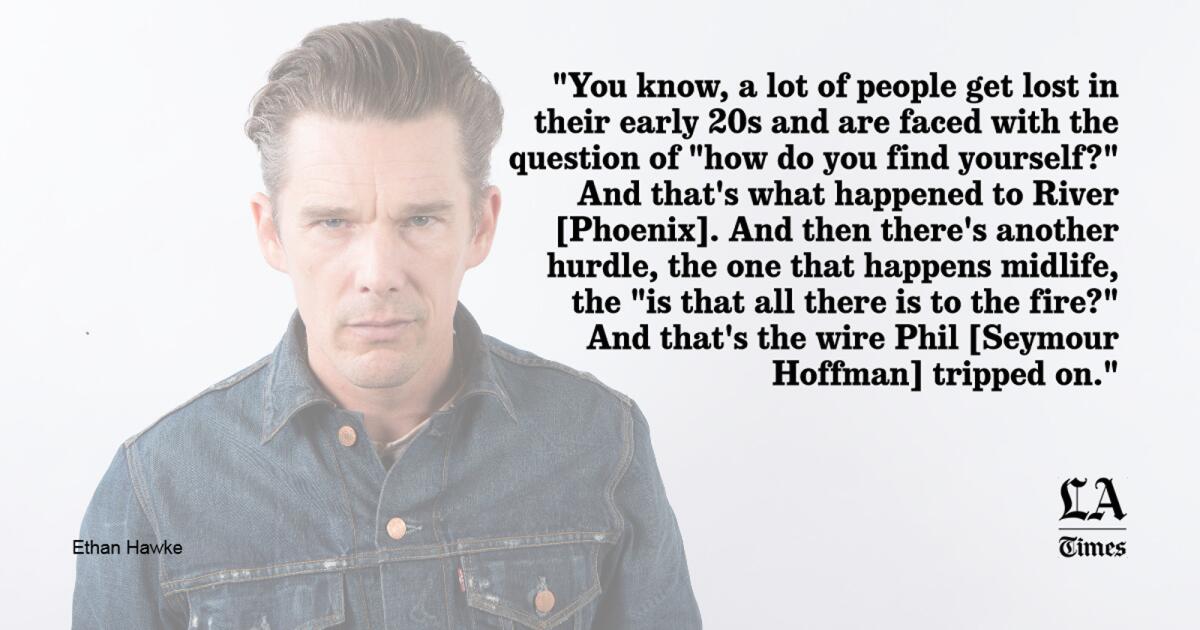

The Times: As I watched this film I also was wondering about someone else who struggled with addiction, who was close to you — Philip Seymour Hoffman. Is he somewhere in this performance?

Hawke: I though a lot about Phil making this movie too. i got the script, this story of an artist with addiction, right after he died. And I was drawn to it because of how nonjudgmental it was. That’s what seemed right about connecting this to Phil. People make mistakes, we all make mistakes and screw up, in a way that even makes sense at the time. I think that’s something that connects Chet and Phil.

The Times: In that same regard there also would seem to be River Phoenix. You and River came of age together, making your debuts in the same movie [1985’s ‘Explorers’]. He, too, wrestled with many of these demons.

Hawke: He’s the other person I dedicated this movie to. River and Phil. Two actors who’ve had a profound effect on my inner life. They were actors who were also artists, and to lose both of them to the same drug...[pauses as he begins to tear up.]

[After collecting himself] A lot of people get lost in their early 20’s and are faced with the question of ‘how do you find yourself.’ And that’s what happened to River. And then there’s another hurdle, the one that happens midlife, the ‘is that all there is to the fire’? And that’s the wire Phil tripped on.

The Times: You knew him well--do you think he had a sense of the tragedy that awaited? It’s easy to think that way in retrospect with but is it something a person is aware of as it’s happening?

Hawke: Not long ago I was watching ‘Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead’ [in which the two starred, Hoffman playing a desperate addict] for this Sidney Lumet retrospective. I was watching a few Sidney movies, and I also watched ‘Before the Devil.’ It’s very difficult for me to re-watch that movie. But I realized seeing it now that it was such a personal performance for Phil. No one was hip to it at the time, but he was playing a person losing a battle with addiction. He was playing himself.

There was a reason you were seeing his story in that film. Phil was ferociously honest with regard to art. People can manipulate the truth, he would say. You can play your friend and you can even play your family. But you can’t play art.

The Times: Watching Sidney’s movies again must have been very poignant too. Do you think the older ones hold up?

Hawke: I watched ‘Network’ as part of this little project, and it was eerie. You can’t believe what it’s predicting. We’re in this moment when people are so angry with the status quo they’re willing to vote for Donald Trump. I would encourage people to watch ‘Network.’ Because Trump is really starting to remind you of Peter Finch. Even the hair. He’s mad as hell, the whole thing. What Paddy Chayefsky knew is incredible. We have turned our election into reality TV show

But that’s the way a lot of our culture is. The Oscars are like that--a lot of people vote for the person the most want to give a speech. Old guys and young women. They’re the best story for the personal narrative. Look at politics. Let’s not have Bernie fall out too soon. Let’s let Sarah Palin fall [during the election cycle] but still keep her in popular culture.

The Times: Do you mean it’s a conspiracy?

Hawke: No. It can sound that way. But I think it’s just the way human nature works. We want to creative the best narrative. And these make the best narratives.

The Times: It’s hard not to wonder what kind of narrative you want in your career. You seem to be in this place where indie passion projects are what most excite you. Then again, four kids, a family, the money isn’t exactly what it once was. And it wasn’t a lot of money when it once was.

Hawke: [Laughs] No, it wasn’t. And it’s not. I’m talking to DC and Warner Bros. about some things. The trick is listening to what I call the dream scenario. For years i always thought, ‘what’s the gap between what they’re promising you and what will happen?’ It’s like ‘we’re going to give you all this money and give you freedom and get you David Mamet.’ And how much of that really is going to happen?

I talked to Mark [Ruffalo] about whether superhero movies make sense. Becaus it’s a different business [as an actor.] But he also said, ‘you can get a lot of indie projects made if you star in one of those.’ You just have to figure out how far from the dream scenario you’re willing to go.

The Times: What are some of those indie projects?

Hawke: One thing I’m working on now is ‘Camino Real,’ based on the Tennessee Williams play. It’s something I’m writing and want to direct, and it’s kind of a pretty radical take, with a burlesque show. And it’s set against the backdrop of Ferguson

The Times: So you’re taking a small swing.

Hawke [laughs]: I know! Serious politics, sex, race. It’s everything mainstream Hollywood can’t get enough of right now.

The Times: And then I have to ask the inevitable Linklater question. No, I won’t ask about a ‘Boyhood’ sequel. But Is there another ‘Before’ movie somewhere in your future?

Hawke: It usually happens that we start talking about a new one five years after the last one. So I think we’re a year or two away from that. We’ll all -- Rick and me and Julie Delpy -- sit down and see what is this one about. What makes sense with where these characters are in their lives. is it the death of a parent, or something else. We do have a title though.

The Times: Oh yes?

Hawke: ‘Before.’

The Times: Just ‘Before?’

Hawke: The letter and number. B:4. Like T:2.

The Times: I see you are thinking in Hollywood terms.

Hawke: Always.

You Might Also Like:

In ’Seymour,’ Ethan Hawke and Seymour Bernstein as creative odd couple

Movie Review: ‘Born to be Blue’

Will Don Cheadle shake the establishment with Miles Ahead?

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.