How Instagram and YouTube help underground hip-hop artists and tastemakers find huge audiences

- Share via

In 2011, Shawn Cotton abruptly quit a minimum wage job cleaning refrigerators at a Best Buy distribution center in Dallas. Down to his last $27, he purchased a MacBook, a cheap video camera and the domain name SayCheeseTV.com. By most conventional metrics, it should’ve been a terrible idea.

When Say Cheese launched, the golden age of blogs had ceased. Instagram’s ascendancy felt preordained. Twitter, Facebook and the short-form site Tumblr reigned supreme. No less than Kanye West, the most famous blogger to ever all-caps rant, had recently shuttered his once thriving kanyeuniversecity.com.

Undeterred, Cotton sleeplessly wrote articles, conducted interviews and filmed Texas rappers freestyling — which he’d edit himself and post on his fledgling YouTube channel and website. It earned him regional clout, but his income was minimal, at least until Cotton had the epiphany that to be a successful blogger, you no longer actually needed a blog.

“I was still trying to do the website thing, but I realized that no one really cared,” says Cotton, whose Say Cheese Media has become one of the most influential contemporary tastemakers and cultural chroniclers of street rap music, all without a regularly updated URL to call its own.

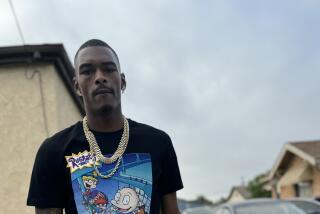

As Instagram and YouTube supplanted blogs, Twitter and Vine as the most popular platform for social engagement among millennials, Cotton followed his audience. All interviews were filmed and uploaded; breaking news and truncated clips of music videos could neatly fit onto a medium that swiftly delivered content in pellet-sized bursts. Most notably, Cotton’s platform helped launch the career of Tay-K, the controversial 17-year-old incarcerated rapper from Arlington, Texas.

Today, with hip-hop having surpassed rock as the most popular music genre, its independent media tastemakers have experienced a commensurate rise in popularity. This is partially due to the social media savvy and innate self-promotional streak of its stars, but it’s also a byproduct of the whims of fans. For every Lil Yachty or Post Malone that comes up squarely within the confines of the major label system, there is a Tay-K or 6ix9ine, Soundcloud superstars, whose court cases and controversies fuel their meteoric rise but who are often treated as persona non grata by mainstream publications.

With the ever-increasing consolidation of urban radio, program directors appear increasingly wary to break below-the-radar local phenomena. Regional tastemakers have capitalized on the void, serving both artists eager for enhanced buzz and fans seeking one-stop shops for videos, intra-city beefs, and interviews with less known musicians.

Without the ethical constraints of traditional journalism, they blur the lines among promoters, reporters, gossip mavens and curators. No one is getting rich, but it opens the doors to vanity labels, podcasts, party promotion, and the hope of eventually joining industry royalty.

“Sometimes you have to change with the times. You can’t fight what’s hot,” says Cotton, 28. “It’s a dumbed down era where people are too lazy to click on a bunch of links to read long articles, especially when they can watch a YouTube video or just scroll through Instagram.”

In the course of one recent 24-hour blitzkrieg, the Say Cheese Instagram (342,000 followers and counting) — which Cotton maintains along with one full-time employee — averaged a post an hour. Updates included the latest videos from regional stars, anniversary dedications to classic albums, murder rate reports and the latest news on who got arrested, who’s beefing and who got beat up.

Says Cotton, “Instagram is like Wal-Mart in that it’s a one-stop shop with everything you need— from money and jewelry being shown off, to music, to the latest sneaker release.”

The phenomenon didn’t occur in isolation. As late as 2010, rap blogs remained impactful enough that Tyler, the Creator eviscerated two of the most popular gatekeepers, Nah Right and 2 Dope Boyz, for refusing to post Odd Future’s music.

Even then, an evolutionary shift began to prize visually alluring content over text-heavy interviews and criticism. The most massive rap website to emerge from the era was WorldStarHipHop, which rewrote the template in comic sans and offered dystopian wormholes of street rap, twerking videos and amateur fistfights shakily taped on cellphones.

“Social media is perfect for attention whores who have a plan,” laughs 03 Greedo, the gifted Watts rapper, singer and producer. His unimpeachable street credibility and gorgeous doomed gospel melodies helped him build a devoted cult fan base on the streets of South Central, but his comic sensibilities built for social media helped him go nationally viral.

“My rapping is great, my singing and production are immaculate, but that’s not what these kids want to hear about. They’re like, ‘That’s the guy who does all the funny stuff,’ ” Greedo says. “Social media controls the music game now, but it also allows us to show the differences between people’s sounds and looks. In L.A., it’s allowed us reveal our real identities — the vigilantes, graffiti writers and gangbangers who are authentic and never follow the rules.”

My rapping is great, my singing and production are immaculate, but that’s what not these kids want to hear about.

— 03 Greedo

The hip-hop blogs originally sprouted from mid-2000s message board culture to flourish as voice-driven personal fiefdoms breaking new artists, excavating obscurities, and spawning critical dialogue.

They eventually devolved into diluted clearinghouses posting dozens of MP3s and videos.

In 2012, with the the social media era in full upswing, a New Jersey-based Jamaican émigré named DJ Akademiks rocketed to fame by chronicling (and many said exploiting) the violent controversies of the Chicago rap boom.

The self-proclaimed “satirists” technique was simple and swiftly replicated. Over gruesome stills of dead bodies and rappers clutching drugs and assault rifles, he’d riff on the daily gossip and trauma. Think Harvey Levin of TMZ narrating “Menace II Society” but catering to hundreds of thousands eager to hear about nascent stars considered too raw for mainstream publications.

With nearly a million Instagram followers and 1.5 million YouTube subscribers, Akademiks could be considered the most popular contemporary blogger even though he doesn’t write — his reach on those platforms far exceeds that of Pitchfork, the most successful music website to emerge in this millennium.

Fittingly, the most popular individual critic of this generation is a bespectacled YouTuber from Connecticut named Anthony Fantano, whose Needledrop channel boasts over 1.3 million acolytes.

In the digital media landscape, the only constant is the accelerated need for more content in myriad forms. If the music blog arose from post-Napster flux to share MP3s with voracious underground audiences, the rise of Spotify, Soundcloud, Apple Music and YouTube partially obliterated their reason for being.

The Rap Caviar and Apple A-List playlists have supplanted radio’s one-time kingmaker dominance. And all you need to be a tastemaker now is a Twitter or Instagram account and a crude facility with the fire Emoji.

A video is straightforward, but a meme can make your mind wander.

— Ray Autry

Yet the blog isn’t totally extinct. Consider it an endangered species.

In Chicago, the decade-old Fake Shore Drive continues to be a civic lodestar. Nearly every notable Southern rapper still first receives national attention via veteran site Dirty Glove Bastard.

While in Los Angeles, the best up-to-the-minute local rap coverage can be found at domains run by upstarts Rosecrans Ave. and SLAP Media. What’s clear is that the website has evolved to become one of several competing content delivery mechanisms in an increasingly complicated and words-averse ecosystem.

“Video is definitely the future, but the website will never die. People still love reading long-form stories too,” says Ray Autry, 31, who runs L.A.-based Kollege Kidd alongside his twin brother, Richard.

Natives of inner-city Toledo, the brothers launched their site in late 2011 with the idea of merging their respective talents in writing and film editing. A former intern at the Wall Street Journal, Richard wrote mostly breaking news and features, which often focused on Chicago rap and its breakout star, Chief Keef. After he finished, Ray converted the pieces into video news stories.

“Kids don’t want to read all the time, they’d rather watch video,” Richard Autry explains a trend that not coincidentally mirrors the cord-cutting tendencies of millennials and Generation Z.

But the Autrys acknowledge that the velocity of the Internet has forced them to constantly adapt faster and develop a new fluency in each medium. What will work on Twitter might not work on their homepage, YouTube or Instagram.

In catering to its 455,000 Instagram subscribers, the Kollege Kid account relies heavily on memes. On any given day, this can mean asking which fast food restaurant you’d choose if a zombie apocalypse forced you to pick just one, or who is the best currently incarcerated rapper.

“Pictures and memes are powerful,” Ray Autry says. “A video is straightforward but a meme can make your mind wander. “

And if that doesn’t work, you can always keep scrolling.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.