Solar panels on California’s canals could save water and help fight climate change

- Share via

This is the April 22, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

By virtue of the fact that you’re reading this newsletter, you’re probably aware today is Earth Day — or as environmental reporters know it, “The day we get even more press releases than usual, but we keep doing the same job we’ve been doing all year.”

So I don’t have a special Earth Day edition of Boiling Point for you. I do, however, have some intriguing information about an idea that always seems to gets folks excited: Putting solar panels over water.

I was initially skeptical when I read about a new study from researchers at UC Merced, finding that covering thousands of miles of California’s largest canals with solar panels could generate huge amounts of clean energy at a reasonable cost, while saving lots of water by reducing evaporation. Published in the journal Nature Sustainability, the study concluded that the “net present value” of canal-spanning solar systems could be as much as 50% higher than solar farms on nearby land.

Don’t get me wrong — at an intuitive level, it makes perfect sense. Install photovoltaic panels atop canals, and avoid the land-use battles over habitat protection and rural community character that are a growing roadblock for the solar industry. Save water in a drought-prone state that can use every last drop. Maybe even improve air quality in the notoriously smoggy Central Valley by using the newly installed clean energy infrastructure, paired with batteries, to replace diesel-powered irrigation pumps.

But when I’d heard these ideas floated in the past, I’d also heard skepticism from the people who run California’s water systems. How much would all that solar power cost? Who would build the power lines to scoop up those clean electrons and send them to faraway cities? And would the panels interfere with maintenance work to patch up aging canals?

At first, it looked like this study would go over the same way. A spokesperson for the state Department of Water Resources, which operates the massive California Aqueduct, issued the following statement to the Modesto Bee, which I tweeted about: “Covering the aqueduct would be an enormous expense and would complicate access to the waterway for maintenance.”

Then a surprising thing happened.

Karla Nemeth, who’s led the water department since she was appointed by then-Gov. Jerry Brown in 2018, tweeted back at me with a different message, telling me her agency is “all ears” and “glad this is getting another look.” Lo and behold, I discovered the statement in the Modesto Bee article had been replaced with a new, more positive comment from the water department, saying the agency is “committed to exploring all opportunities to embrace renewable energy to reduce our carbon footprint.”

Naturally, I set up a call with Nemeth to ask her what was going on.

She told me the State Water Project — a 700-mile system of aqueducts, reservoirs and pumping plants that mostly moves water from the state’s wetter northern reaches to its drier south, and which is California’s single largest electricity user — has a goal of 75% climate-friendly power by 2030. That’s up from 65% currently, much of it hydropower generated at the agency’s dams.

Nemeth sees solar panels over canals as one option for reaching 75%, and for complying with a state mandate of 100% by 2045.

She also said last August’s rolling blackouts highlighted the close connections between California’s energy and water systems, and the need for canal operators to think creatively about how those two systems can work together.

What did last summer’s events have to do with water?

A lot, as it happens. The Department of Water Resources generated hundreds of megawatts more power than normal from its hydropower dams, helping to limit the need for blackouts as a heat wave prompted Californians to keep their air conditioners humming after dark. The water department also cut back on pumping at strategic times, reducing its own electricity use.

On the flip side, the heat wave drew attention to the reality that rising temperatures are contributing to harsher droughts, which in turn results in less emissions-free electricity generation at hydropower dams — a reality that California will likely face this summer, with a new drought hitting the state even as Gov. Gavin Newsom’s team scrambles to make sure the lights stay on.

“Last summer was a real wake-up call for how the water system supports the grid,” Nemeth said.

To be clear, Nemeth still has serious questions about covering large canals with solar panels. She pointed to several obstacles, including the cost of the support structures, which she said would make the electricity far more expensive than what her agency pays on the wholesale market. Insufficient power lines and access to canals for maintenance are possible barriers too.

She was similarly cautious when I asked her about solar panels on water reservoirs, a question prompted by the recent news that two wastewater treatment ponds in Sonoma County are now home to the nation’s largest floating solar farm.

All that said, Nemeth thinks both concepts are worth exploring.

“We do have a need to reinvest in the State Water Project, so we should do it with a mentality and understanding of the challenges that are coming at us, one of which is climate and energy,” she said.

The idea for the UC Merced study came from a Berkeley-based marketing firm called Citizen Group, whose principals are trying to put the solar canals idea into action. They’ve started a company called Solar AquaGrid LLC that’s looking to develop pilot projects with smaller water agencies that operate their own canals. If and when that happens, expect a story from me.

There’s no question more research and testing is needed. Not many solar canal systems have been built, meaning the researchers largely relied on a few projects in India for cost estimates. The study’s projected water savings of 200,000 acre-feet annually is almost certainly an overestimate, since it assumes 4,000 miles of large canals would be covered with solar, which isn’t likely. The same is true of the estimated 13 gigawatts of solar energy, which would equal one-sixth of the state’s current power capacity.

At the same time, the study didn’t capture all the potential benefits of canal-spanning solar canopies, according to Roger Bales, an engineering professor at UC Merced and one of the authors.

Replacing pollution-spewing diesel pumps in the Central Valley, which the researchers didn’t explore in detail, could improve public health. Keeping some amount of undisturbed land from getting paved over with solar panels could protect biodiversity and support Newsom’s “30 by 30” goal to shield nearly one-third of California’s land and waters from development by 2030.

“The economics are attractive because of the multiple benefits,” Bales said.

But therein lies a challenge for a lot of seemingly straightforward ideas that could stem the climate crisis and otherwise help people and the environment: The costs and benefits aren’t always shared by the same people or communities.

In this particular case, installing solar panels over canals may have plenty of advantages. But why would the Department of Water Resources agree to pay a higher price for electricity when it’s only going to see a fraction of the benefits itself?

I discussed that question with Felicia Marcus, a former chair of the State Water Resources Control Board, who offered some guidance to the UC Merced researchers and was excited by their results. She told me their vision isn’t likely to become a reality unless government agencies and entire communities can find creative ways to break down silos and work together.

“Maybe it’s going to cost you a little more on the energy side, but you’re going to get a little more on the water side. And not everything is about money,” Marcus said.

“None of this is as simple as people think it is,” she added. “And yet as people professionalize, they get so buried in the details that sometimes they can’t see the magic and the wonder and the common sense of the idea.”

Magic and wonder and common sense. We could use more of that, don’t you think?

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

California may be a climate leader, but that doesn’t mean it’s doing enough. Despite what I said earlier, here’s an Earth Day special: I talked with UC Berkeley climate expert Daniel Kammen about his new paper arguing California needs to start slashing planet-warming pollution much more quickly. The state has long been a leader on confronting the climate crisis, but Kammen and his collaborators say it’s falling behind as European countries and other U.S. states begin to set more aggressive targets.

Three years ago, then-Gov. Jerry Brown said California would launch its “own damn satellite” to fight climate change if the Trump administration wouldn’t. Now it’s actually happening. The Times’ Tony Barboza reports the state is preparing to launch two satellites to find and track methane “super emitters” responsible for a wildly disproportionate share of the planetary warming we’re all currently experiencing. Those super emitters include landfills, composting facilities, dairies and oil and gas operations.

With time running low to get climate change under control, it’s time to bring out the carbon vacuums. That’s the takeaway from this story by my colleague Evan Halper. The world will need a mind-boggling number of solar panels, wind turbines and other clean energy facilities to replace fossil fuels, but we’re late enough in the game that simply cutting emissions is no longer enough. That’s why California and the Biden administration plan to invest in machines that can suck carbon out of the atmosphere.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

All eyes are on the White House as President Biden hosts a virtual climate summit Thursday and Friday. One big question is whether the president will be able to convince China, Japan and South Korea to stop financing coal-fired power plants around the world, as Anna M. Phillips and Tracy Wilkinson report for The Times. Scientists and activists are also urging Biden to roughly double America’s own climate target and aim for an emissions cut of 50% by 2030. He’s expected to do so, my colleague Chris Megerian reports. Vice President Kamala Harris, meanwhile, was in North Carolina talking about the benefits of replacing diesel school buses with electric buses, per The Times’ Noah Bierman.

Will Trump’s border wall be taken down? That’s the question at the heart of this jarring and thoroughly reported story by the Arizona Republic’s Erin Stone, Anton L. Delgado and Ian James, who saw firsthand how the 30-foot steel wall and its builders have blown up mountains and cut across rivers. President Biden stopped construction, but it’s not clear what he’ll do next.

A new study concludes that tyrannosaurs, known as T. Rex, likely hunted in packs rather than solo. You may be wondering what this story is doing in a newsletter about climate and the environment. Well, the research was based on fossils found at Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, possibly bolstering the case for Biden to restore the monument to its pre-Trump boundaries, as Juliet Eilperin reports for the Washington Post. The place is a treasure trove of geologic history.

A judge put the brakes on a sprawling housing development at Tejon Ranch north of Los Angeles, ruling the environmental review was inadequate on wildfire risk and climate pollution from car traffic. My colleague Louis Sahagún has the details.

WATER IN THE WEST

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

California may be suffering a decades-long megadrought. Yes, this “new” drought currently getting started could be part of a longer-term phenomenon on par with the worst dry spells of the last 1,000 years, although there’s debate among researchers on that point, my colleague Alex Wigglesworth reports. Climate change is also worsening water scarcity in the already-parched nation of Jordan, where The Times’ Middle East bureau chief, Nabih Bulos, reports that people make do with 135 cubic meters of water per person per year, on average. The United Nations defines “absolute scarcity” at 500 cubic meters.

Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a drought emergency — but only in two counties, in Northern California’s Russian River watershed. The governor declined to issue a similar order for the entire state, despite the urging of Central Valley Republicans who want to see water quality and environmental standards relaxed, The Times’ Bettina Boxall reports. A long-term water supply problem is also afflicting Borrego Springs, which is surrounded by Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and has been draining its groundwater aquifer for decades. To keep the town alive, locals have reached a painful agreement to cut their water use by 74% over the next 19 years, Janet Wilson reports for the Desert Sun.

A rural utility east of Seattle wants to use hydropower to generate hydrogen at an old apple orchard. While that may sound like a Mad Lib of clean energy and American West buzzwords, it’s the subject of this story by the Seattle Times’ Hal Bernton and Inside Climate News’ James Bruggers. There are times of year when turbines on the Columbia River produce more electricity than needed, and a public utility wants to use that excess power to create a clean-burning fuel for factories, trucks or power plants.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

It’s been two and a half years since the Los Angeles City Council said it wanted annual inspections of all oil and gas drilling sites. But those inspections still aren’t happening, Emily Alpert Reyes reports for The Times. The city’s petroleum office is down to two staff members, and environmental justice activists say City Council members have basically abandoned communities on the front lines of fossil fuel pollution, even as they continue to entertain the idea of phasing out oil and gas production in the city.

Nevada’s largest natural gas utility is using many of the same tactics as its Golden State counterpart, Southern California Gas, to fight policies that would promote electric heating and cooking. The Nevada Independent’s Daniel Rothberg and Riley Snyder have an inside look at the company’s strategy, which includes building support for the idea that ditching gas would harm people of color by raising energy costs. Also see my story from last year on how that argument is being used in California.

Several people have died in Tesla crashes when running their cars on Autopilot, which despite Elon Musk’s claims does not allow for “full self-driving.” Thus far, California regulators and federal officials have let the company get away with those claims, my colleague Russ Mitchell reports, although it’s possible a fatal collision in Houston this past weekend will change that.

ONE MORE THING

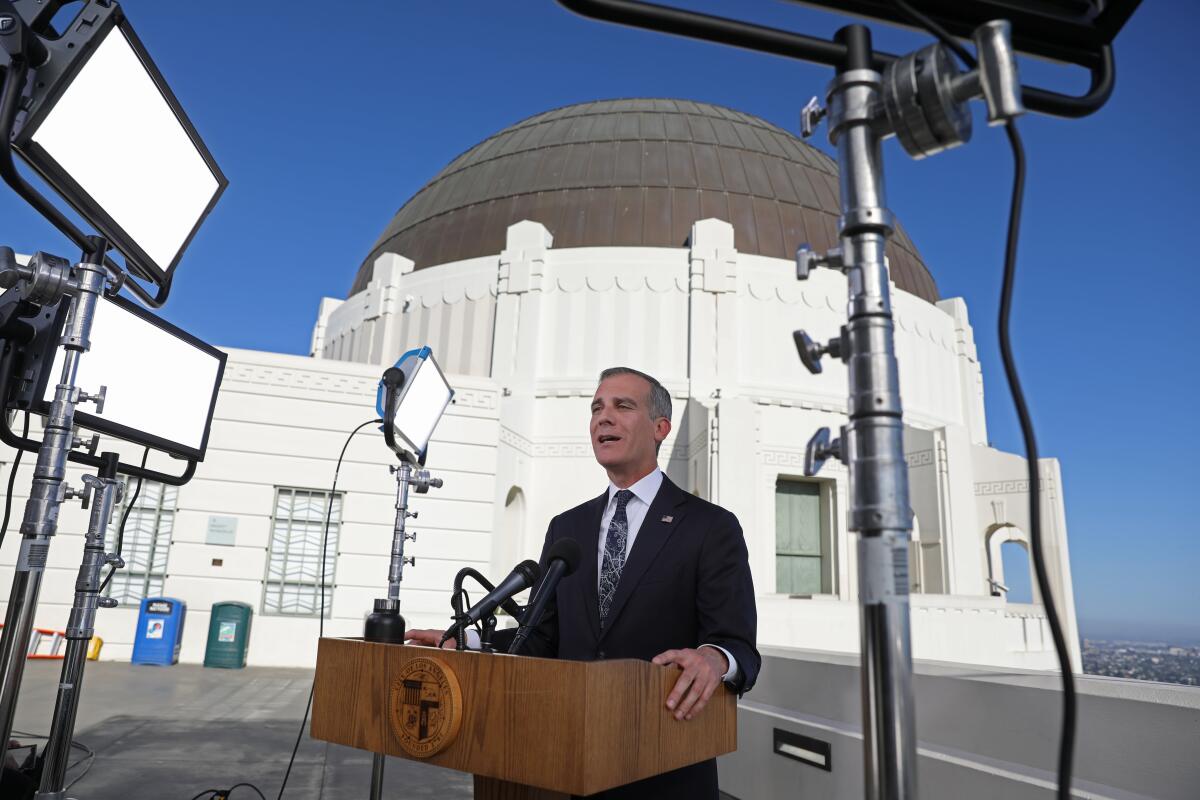

I was talking this week with Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti about his decision to set a citywide goal of 100% clean energy by 2035, when he mentioned something about his past that I didn’t know: About 30 years ago, as a student at Columbia University, he took a class taught by Wally Broecker, often referred to as the “grandfather of climate science.”

Garcetti told me he took Broecker’s class, Design and Maintenance of a Habitable Planet, because he thought it would be “the easiest science to take.” But the lessons struck a chord with him, and he kept his notes. He reviewed them recently and couldn’t help but wonder what was going through his mind as a 19-year-old, hearing the emerging evidence of a planetary disaster.

It’s discomforting to think about how many decades we’ve let slip through our fingers as a society without committing to large-scale, coordinated action. At the same time, it’s encouraging to realize how much can still be done despite all that lost time.

For now, Happy Earth Day. Let’s do this again next week.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.