- Share via

WEITCHPEC, Calif. — At first, the dead floated downstream a few at a time. Then they came by the hundreds, and then the thousands.

For mile after mile, the Klamath River was filled with tens of thousands of dead salmon. As Annelia Hillman paddled a canoe with a friend one September day 21 years ago, her heart sank when she saw the carcasses floating past. She and other members of the Yurok Tribe say they will never forget the stench of death.

“It’s like seeing your family perish in front of you,” Hillman said. “I would compare it to a massacre, really, in terms of the emotions and the trauma that it has caused for us.”

The grief drove Hillman, then 27, to begin protesting to demand change. The mass fish kill of 2002, estimated at up to 70,000 salmon, became a defining event for a generation of young Native activists — a moment that showed the river ecosystem was gravely ill, and badly in need of rescuing.

Water diversions for agriculture had dramatically shrunk river flows. And the Klamath’s hydroelectric dams, which had long blocked salmon from reaching their spawning areas, had degraded the water quality, contributing to toxic algae blooms and disease outbreaks among the fish.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

At first, when Indigenous leaders demanded that dams be removed, their chances of success seemed remote at best. But after more than two decades of persistent efforts, including protests at company shareholder meetings, demonstrations on the river and complicated negotiations, the four dams along the California-Oregon border have finally started to be dismantled.

One small dam has already been removed, and three more are slated to come down next year.

For members of the Yurok, Karuk and other tribes who have been immersed in the struggle for much of their lives, the undamming of the Klamath represents an opportunity to heal the ecosystem and help fish populations recover by opening up hundreds of miles of spawning habitat. They say the coming changes hold promise for them to strengthen their ancestral connection to the river and keep their fishing traditions alive.

“This river is our lifeline. It’s our mother. It’s what feeds us. It’s the foundation to our people, for our culture,” Hillman said. “Seeing the restoration of our river, our fisheries, I think is going to uplift us all.”

Work on the dam removal project began in June. The smallest dam, Copco No. 2, was torn down by crews using heavy machinery. The other three dams are set to be dismantled next year, starting with a drawdown of the reservoirs in January.

“The scale of this is enormous,” said Mark Bransom, CEO of the nonprofit Klamath River Renewal Corp., which is overseeing dam removal and river restoration efforts. “This is the largest dam removal project ever undertaken in the United States, and perhaps even the world.”

- Share via

The $450-million budget includes about $200 million from ratepayers of PacifiCorp, who have been paying a surcharge for the project. The Portland-based utility — part of billionaire Warren Buffett’s conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway — agreed to remove the aging dams after determining it would be less expensive than trying to bring them up to current environmental standards.

The dams were used purely for power generation, not to store water for cities or farms.

In a welcome harbinger for fish, tribes and the environment, four Klamath River Basin dams will finally come down.

“The reason that these dams are coming down is that they’ve reached the end of their useful life,” Bransom said. “The power generated from these dams is really a trivial amount of power, something on the order of 2% of the electric utility that previously owned the dams.”

An additional $250 million came through Proposition 1, a bond measure passed by California voters in 2014 that included money for removing barriers blocking fish on rivers.

Crews hired by the contractor Kiewet Corp. have been working on roads and bridges to prepare for the army of excavators and dump trucks.

“We have thousands of tons of concrete and steel that make up these dams that we have to remove,” Bransom said. “We’ll probably end up with 400 to 500 workers at the peak of the work.”

During a visit in August, Bransom stood on a rocky bluff overlooking Iron Gate Dam, where crews were working on a water drainage tunnel.

There won’t be major dam-wrecking explosions, he said, but workers plan to blast open some dam tunnels to move out tons of accumulated sediment from the reservoirs. As the water is drained, crews working on boats will also spray fire hoses to wash away muddy silt and send it downstream.

In addition to tearing down the dams, the project involves restoring about 2,200 acres of reservoir bottom to a natural state.

In recent years, workers have collected nearly 1 billion seeds from native plants along the Klamath and sent seeds to farms to be planted and harvested. That has produced nearly 13 billion seeds — 26 tons in all — which will be planted once the reservoirs are drained.

The aim is for native vegetation to regrow across the watershed while fish begin to access 420 miles of spawning habitat in the river and its tributaries.

“Nature knows what it wants to do. So what we’re really trying to do here is work with Mother Nature to create conditions that will allow for river healing and for restoration of balance here,” Bransom said. “We can offer a light touch to help nudge things in the right direction.”

Fed by Cascade Range snowmelt, the Klamath River takes shape among lakes and marshes along the California-Oregon border and winds through steep mountainous terrain before ending its journey among redwood forests on the Pacific Coast.

For the Yurok, the fight to remove dams is the latest in a series of struggles over the river’s management and the preservation of their way of life.

Susan Masten, a leading advocate for tearing down the dams, recalls a time in 1978 that the Yurok call the “Salmon Wars,” when federal agents descended on the reservation to enforce a ban on fishing.

Just five years earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court had affirmed the tribe’s fishing rights in a landmark case involving Masten’s uncle, Raymond Mattz. But federal officials had ordered a halt to tribal fishing on the Klamath even as other fishing continued along the coast.

The Yurok, who sought to defend their fishing rights and tribal sovereignty, faced off with officers in riot gear holding billy clubs and M-16 rifles. Many residents feared for their lives, Masten said.

Masten recalled seeing officers drag a woman away by her hair as tribe members protested on a riverbank. Another time, she said, agents twisted her grandfather’s arm behind his back.

The tensions eventually subsided when the marshals left, and the Yurok successfully asserted their rights to continue fishing. But they saw other threats in the declining fish populations — and the four hydroelectric dams that were built without tribal consent between 1912 and the 1960s.

Masten, who was the tribe’s chairperson during the devastating fish kill of 2002, was ecstatic when federal regulators signed off on plans to demolish the dams.

“I really didn’t think that I would see dam removal in my lifetime,” Masten said.

Masten, who is 71, spoke while drifting across the estuary in a motorboat near the river’s mouth. As the surf crashed against a barrier of sand, pelicans, cormorants and ospreys soared over the dark water.

“Everything that’s around here is connected to this river,” Masten said. “And so for us to ensure the future for our children, we need to ensure that this river is here and that it’s healthy, and that the ecosystem is healthy, because it’s the heartbeat of our people. It’s the lifeway of our people.”

Federal regulators have approved a plan to demolish four Klamath River dams, a historic act that is intended to save imperiled salmon.

Masten lives in her ancestral village of Rek-woi, or Requa, in a home on a bluff overlooking the river’s mouth. Once the dams come down, she said, she expects to see the fish thrive and the entire ecosystem flourish.

“The river has a way to heal itself, and it can heal itself very quickly if it’s allowed to do so,” Masten said. “I’m excited that my grandchildren will be able to benefit from it.”

Masten’s niece, Amy Bowers Cordalis, is a lawyer for the tribe who focuses on the Klamath River and was involved in negotiating agreements involving California, Oregon and PacifiCorps to enable dam removal.

“We kept pushing and pushing,” Bowers Cordalis said. “We all came together and figured out a way to remove dams.”

She stood by a boat ramp that in August typically would be bustling with families hauling out their nets and fish. But the ramp was mostly deserted.

The tribe’s leaders took the rare step of canceling subsistence fishing this year to protect the dwindling salmon population, a decision that mirrored the shutdown of commercial fishing along the coast.

Several years ago, Bowers Cordalis also worked on the Yurok Tribe’s declaration of the river as a legal “person” under tribal law, a step intended to provide greater protections.

One key problem, she said, is that the dams have allowed nutrient-filled agricultural runoff to fester in lakes, feeding algae blooms. When the river isn’t safe for bathing, it prevents the tribe’s members from carrying out ceremonies that involve entering the water.

Tearing down the dams is a first step in “a new era of healing,” Bowers Cordalis said. She said she hopes to eventually get back the flourishing river with abundant fish that her great grandmother saw a century ago.

From the river behind her, a salmon flew into the air, its scales shimmering, and landed in the water with a plop. Then another salmon jumped.

“A big run just went through!” a man called out from a boat.

Bowers Cordalis said it was encouraging to see that some salmon, even with their population so low, were making it upstream to spawn.

“We have so much hope that this river will restore itself,” Bowers Cordalis said. “Dam removal is just the beginning. Dam removal is the end of colonization of this river.”

Not everyone is happy to see the dams go. In some areas, the removal project has generated heated opposition.

In the community of Copco Lake, some residents live in waterfront homes with boats and docks. Their homes will be left high and dry when the reservoir is drained.

Alan Marcillet, a resident who enjoys kayaking, said most people in the community aren’t looking forward to the disruptive changes.

“It’s just going to be a mud pit,” Marcillet said. “The community will just die. I would think of the hundred people that live up here, perhaps half of them won’t return.”

Two of his neighbors, German and Jeanne Diaz, bought their retirement home overlooking the lake more than two decades ago. Now, their view is about to change dramatically, and they say they’re concerned about whether the mud that’s exposed at the bottom of the reservoir will turn to dust and pollute the air.

“What is it going to do to the community?” German Diaz said. “Are we going to be going through sandstorms for a while?”

The Klamath River Renewal Corp. has been accepting claims from landowners to pay for damages linked to dam removal. But Diaz said he doesn’t plan to apply for that money.

“We’ve already seen property values drop,” Diaz said. “What can we do?”

Other residents said they see the reservoir as beneficial because it attracts wildlife and serves as a water supply for firefighting helicopters.

Geneve Spannaus Harder, an 80-year-old resident whose great grandfather once owned an apple orchard on lands now submerged by the reservoir, said she and many others strongly oppose draining the lake.

“It’s just going to change the whole scenario of the community,” she said. “I don’t think we know what we’re going to get.”

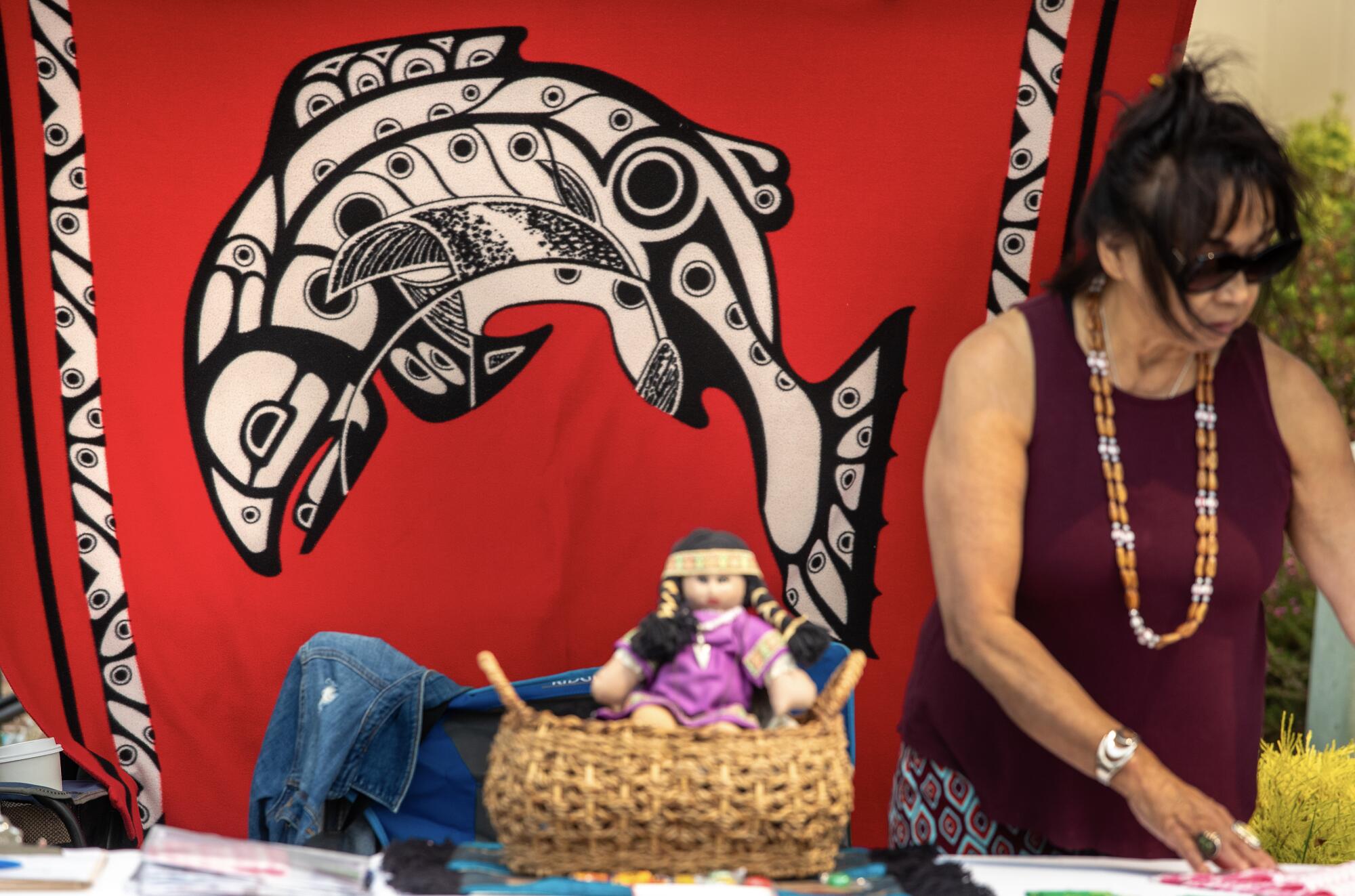

This August, when the Yurok Tribe held its annual Klamath Salmon Festival, no salmon was served. Instead, there were tri-tip sandwiches and frybread, and the parade featured a skit about dam removal with participants holding large paper cutouts of fish.

At one stand, people were asked to write a few words on cards about their hopes for the Klamath River’s future. The cards were hung on strings. One read: “I wish for the salmon to recover and run free forever!”

Nearby, T-shirts were being sold with an illustration depicting the undamming. It features a young woman, her eyes covered with ceremonial bluejay feathers, balancing two baskets like the scales of justice as water breaks through a dam and surges into the river.

The artist, 23-year-old Tori McConnell, said the young woman represents both the people and the river in a state of transition. The tears running down her cheeks are like her prayers, McConnell said, “overflowing into the baskets of justice.”

McConnell, a Yurok Tribe member who is this year’s Miss Indian World, said she is hopeful.

“There’s a lot of work to be done to restore the salmon population,” McConnell said. “But I hope we will see that happen in our lifetime.”

Populations of chinook and coho salmon, as well as other fish, have declined more than 90% in the Klamath over the past century, said Barry McCovey Jr., the Yurok Tribe’s fisheries director.

The dams have been a big factor, he said, and “we have our eyes on righting that wrong.”

As dams and global warming push endangered California salmon to the brink, a rescue plan is taking shape — and a tribe pushes for recovering their sacred fish.

But fish populations have also been ravaged by other factors, including gold mining that scarred the watershed, and decades of logging that left denuded areas, releasing fish-harming sediment into the river.

Additionally, fire suppression in forests over the last century and the lack of traditional burning by Indigenous people has left forests primed for catastrophic wildfires, unleashing tainted runoff that becomes “poison to the ecosystem,” McCovey said.

“You combine all that together, and then you layer on top of that climate change,” he said.

The Klamath’s water is heavily used to serve agriculture, irrigating crops such as onions and hay. The Yurok Tribe is suing the federal government over decisions that they argue don’t provide the minimum flows required for fish, including threatened coho salmon.

The removal of dams is a pivotal milestone and it comes at a critical time for struggling salmon populations, McCovey said, but recovery isn’t going to happen in a couple of years.

“We have to accept that these things take time,” McCovey said.

“I don’t think in my lifetime I’ll ever see a fully recovered Klamath River ecosystem,” he said. “And maybe no one will ever see that. But the goal is to move closer to that.”

McCovey said restoring balance to the ecosystem will take generations, and he is prepared to continue working toward that goal.

In the meantime, he and others have been talking about what they will do once all the dams are gone.

McCovey said he hopes to take a rafting trip, traveling for miles with the current as the river flows freely once again.