An artist trades abstract canvases for pop-up soul food

- Share via

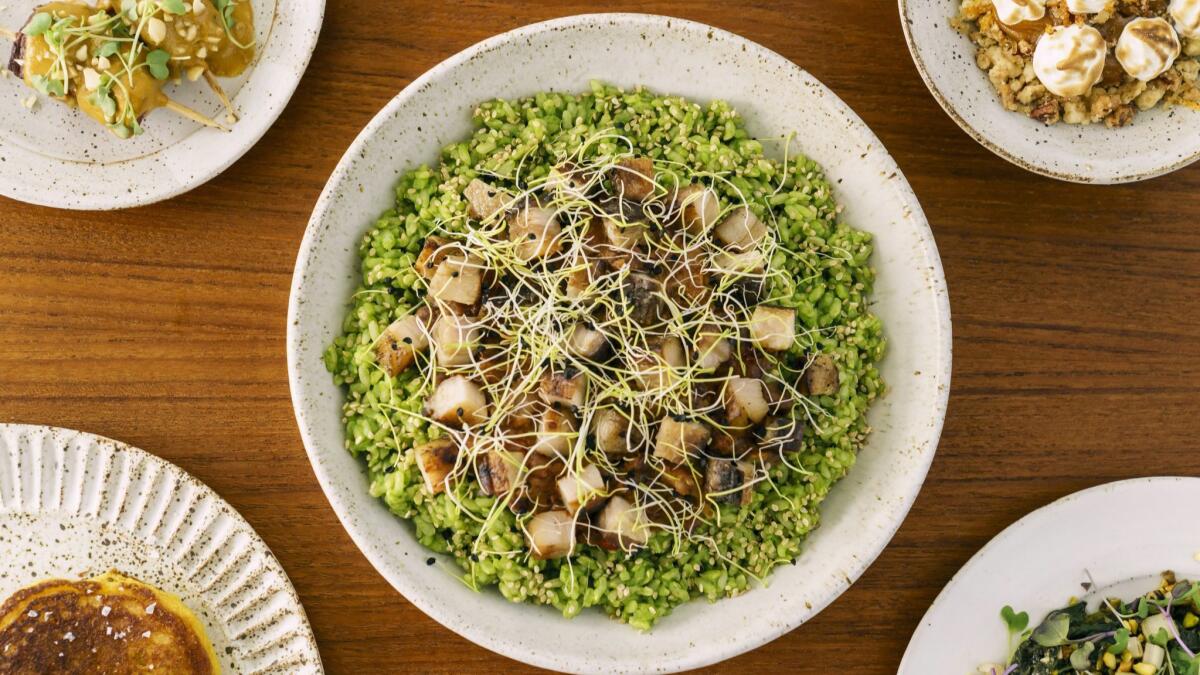

Under an overcast February sky at Paramount Pictures’ backlot — which was set up to resemble a New York City street embedded with art installations, including paintings of laundry strung between faux brownstones — Ray Anthony Barrett plated a meticulous and tiny take on hoppin’ John, deconstructed sweet potato pie and diminutive Maldon salt-studded hoe cakes.

It was the Los Angeles debut of the Frieze art fair; it was also a fitting if perhaps ironic setting for Barrett to be doing his culinary pop-up Cinqué. He spent most of his life not as a cook but as a visual artist, not unlike the 70 or so vendors whose art filled the fair. He’s won awards; he’s had solo exhibitions. But cooking is his central form of expression now.

“The interesting thing about going from art to food is realizing that food is the most political thing,” said Barrett, his tortoiseshell glasses and graying goatee providing a look less culinary than academic. His most recent tattoo? From Apicius, the 1st century Roman cooking book.

“All these stories are embedded into food: culture, access, environment.”

Barrett calls his food project Cinqué because he is Ray Anthony Barrett V but also as reference to Joseph Cinqué, the West African man who led the 1839 revolt aboard the slave ship Amistad.

As Barrett scattered onion sprouts and benne seeds over his hoppin’ John, made with Rancho Gordo beans and rice from Koda Farms, and given funk with a dice of Peads & Barnetts bacon he’d cured himself, he considered his path from Portland, Ore., art school to manning a rice cooker under an outdoor tent the color of his chef’s whites.

He describes his cooking as soul food, quoting the chef Carla Hall’s definition of the term. “It’s like the difference between a hymn and a spiritual,” wrote Hall in her new cookbook, contrasting Southern food with soul food. (Also, wrote Hall: “black cooks.”)

He planted a tiny spoon into a cup of sweet potato purée and cream dotted with crispy bits of sugared pastry, as he told me the prisms of his cooking are his mother’s Kansas City, Mo., kitchen, many hours watching the Food Network, a stint during art school in Senegal (“all I could remember was the food”) and a lot of research.

“I think very few people realize how much research goes into art,” Barrett said a few weeks later as he cooked in the kitchen of the Spanish-style, ’20s-era apartment he shares with his wife, Samira Yamin, a visual artist who helps with pop-ups, and their two cats, Rocky and Apollo (he is a devout fan of the “Rocky” franchise). Their apartment is, predictably, loaded with art, including some of Barrett’s work, intricate animal-focused line drawings, plus repeating stacks of books (Taschen’s Atlas of Human Anatomy and Surgery, Escoffier, David Hockney, Samin Nosrat, Jorge Luis Borges, John T. Edge, John Baldessari, the first Joe Beef cookbook).

Talking to the Joe Beef chefs, who wrote a cookbook about the end of the world »

Barrett holds an MFA and has a day job, as art assistant to the artist Mark Grotjahn, but what he’s been focused on for the last five years is cooking. Barrett moved to Los Angeles after graduating from the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, mounted shows and had some success, but by early 2014 he was burnt out and drinking too much. So he got sober and started filling his weekends with cooking projects.

“It’s ironic, because a lot of the pejoratives in the art world are strengths in the food world,” said Barrett. “A dependence on craft. Nostalgia. But nostalgia is a really big strength in food.” As is “making something beautiful,” something that he says can be a criticism in visual arts these days.

Barrett worked at a catering kitchen and did stages at Naomi Pomeroy’s Portland restaurant Beast, at JuneBaby in Seattle and at Jeremy Fox’s Santa Monica restaurant Rustic Canyon. “I knocked on the back door; somebody said that’s what you do. And so I showed up with my knife roll and my clogs, and Jeremy was like, ‘Here, I’ll get you an apron.’ ”

“We loved Ray. Real quickly he was part of the family,” Fox told me by phone. Barrett worked at Rustic Canyon for about six months, from dishwashing to pastry to working the line to making staff meals. “He’d do these great African-inspired meals,” said Fox, who eventually offered Barrett a full-time position. (Barrett kept his art day job.)

Barrett befriended Robin Koda, the Japanese American farmer who runs Koda Farms with her family, and Minh Phan, the chef of Porridge + Puffs. Phan lent him her rice cooker for the Frieze event and said of Barrett, “I think his food and cooking is a way for him to explore his roots, making it relevant for people who don’t have the same connection as he does. All done on his terms, in his narrative — a narrative that I think is important for L.A. right now.”

Review: At Porridge + Puffs, rice is Minh Phan’s canvas for sophisticated self-expression »

He did his first pop-up last summer at the Underground Museum, an art space in Arlington Heights. A few catering gigs followed, then the pop-up at Frieze, where he was one of a few food vendors, alongside Jessica Koslow’s Sqirl Away and chef Kwang Uh’s cult Korean project Baroo.

“Why do I cook what I cook?” Barrett repeated when I asked him the question as he stirred his version of greens, a sauté of mustard greens, kale and chard bound together with avocado and finished with pistachios and lime. “I saw some chefs cooking hoppin’ John” — a quintessential Southern dish traditionally made with field peas, rice and ham — “and it didn’t look like the hoppin’ John I grew up with. And I felt like I had something to contribute.” He started out with his mother’s recipe, then added some technique, and eventually transformed it, “personalizing it” to the version he now serves, which is just as California as it is Southern. “The only way I can own it is to make it current.”

Barrett’s take on maafe, a West African groundnut stew, translates into short rib skewers grilled on an outdoor hibachi, then topped with peanut sauce and wasabi sprouts; his hoe cakes, made with Anson Mills corn — he routinely employs ingredients from small producers committed to heirloom sourcing or growing — and kefir, are small unsauced disks. The deconstructed sweet potato pie he makes in his kitchen is topped with torched meringue and plated on a gorgeous saucer from Mount Washington potter Beth Katz; Barrett’s version of bissap, “the OG red drink,” is made with hibiscus, orange flower water, mint, ginger and sparkling water.

“I wanted to create a road map,” Barrett said, one that traced his family’s heritage from West Africa to Louisiana and Alabama to the Midwest and eventually to California. “Food brings its own past with it,” said Yamin, perched on a chair, eating warm hoe cakes in her kitchen. “You’re pulling these histories into the present.”

Where Cinqué goes from here, Barrett is still feeling out. More pop-ups and events, more catering gigs. He’s still got his day job, the art on the walls coexisting with the art on the plates. “Right now, it’s closer to a project than a regular job,” said Barrett. “We don’t want to be the help.”

Cinquelosangeles.com; Instagram: @cinque_la, @rayanthonybarrett.

Get the recipe for Ray Anthony Barrett’s “California Greens”:

California Greens

Instagram: @AScattergood

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.