Coffee in L.A.: Above and beyond a cup of joe

A new wave of Los Angeles-area cafes is brewing up more sophisticated flavors with a mix of methods. The result? A jolt to a coffee culture steeped in ho-hum tastes.

- Share via

Coffee shops: An article in the July 14 Food section described Paper or Plastik cafe as being in Pico Village. It is in PicFair Village.

Los Angeles has never lacked for stimulation, but when it comes to coffee its tendencies, like much of the rest of the country's, have been more about habit than taste. Oh, sure, coffee joints are ubiquitous, both the homegrown variety (Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf) and the interlopers (Starbucks, Peet's, Seattle's so-called "Best").

But when, in the middle of the last decade, artisan roasters and skilled baristas started to raise the bar on coffee culture yet again on the West Coast -- at Vivace and Victrola in Seattle, Stumptown and Ristretto in Portland, at Blue Bottle, Four Barrel and Ritual in San Francisco -- L.A. was mostly left behind.

That's changing. In the last year or so, a modest boom of connoisseur-grade coffee bars has sprung up in neighborhoods all over L.A., bringing with them a burgeoning interest in judiciously roasted coffee, brewed to exacting standards, employing elaborate methods of extraction.

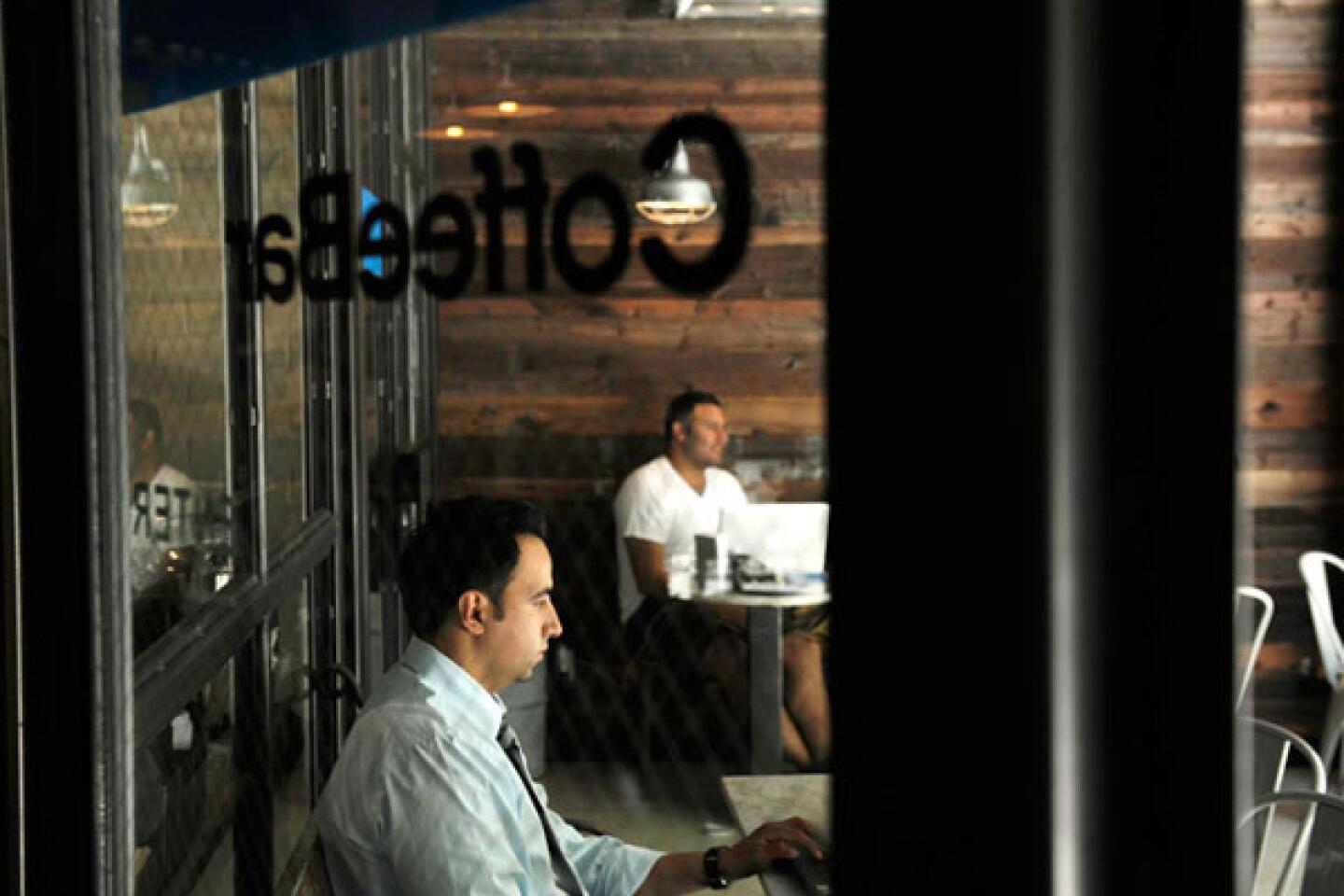

This new wave of cafés -- Balconi Coffee, Cafecito Organico, the Coffee Commissary, CoffeeBar, Cognoscenti Coffee, Gelato Bar, and Paper or Plastik among them -- is dripping, steeping and pulling some very exotic flavors from these roasts and blends. The best cup of coffee you've ever had may be waiting for you in one of these cafes, a pleasure well beyond the usual desultory jolt of caffeine, one in which the complexity and depth of flavor in each sip are as memorable as in a glass of great wine.

An elevated coffee culture has existed in isolated pockets in Los Angeles for more than two decades, in places such as Caffe Luxxe in Santa Monica, the Conservatory for Coffee in Culver City and especially in the efforts of Martin Diedrich in Orange County, whose long family history with coffee growing, importing, conscientious roasting and devotion to café culture, first with Diedrich Coffee and now with Kéan Coffee shops, has been among the most steadfast and progressive in Southern California.

But L.A.'s coffee culture got a serious kick in 2007 when Intelligentsia, a Chicago roaster and café company, decided to put down roots in Silver Lake's Sunset Junction. One year later Craig Min, from a La Cañada family of roasters, opened LAMill, with hand-picked selections from several continents and multiple made-to-order brewing options. Only in the last year or so has that level of sophistication ventured much beyond Silver Lake.

That level of attention is what separates the new cafe from the rote Starbucks experience. Gone are the hot plates, the glass pots, the industrial cauldrons. Each cup or pot is brewed to order, the coffee is measured and ground, the water (filtered, of course) is measured, heated to a few degrees shy of boiling and poured gently over the grounds to create a "bloom," or foam of gases, steeped and released. As such, the new cafe is a slow cafe. But for your patience, you'll be rewarded with a more fussed-over cup of coffee than you ever thought possible.

New brewing methods seem to burst on the scene each month. Most have evolved from some version of the old-fashioned drip cone, the French press or a combination of the two. In your typical cafe, a barista staffs a pour-over bar where a half-dozen cones are perched over porcelain cups. Some cafes use a stoppered drip cone called the Clever, which steeps the coffee before it drains into the cup, or the AeroPress, a nifty variation of the steep-then-drip method. The hourglass-shaped '70s-throwback Chemex carafe has been given new life in a few shops. Then there are various siphon systems that work similarly to your parents' old percolator -- ornate, double-chambered glass bulbs suspended above an open flame, with a setup that wouldn't look out of place in a high school chemistry lab.

Finally there are espresso delivery devices. The newest machines, from La Marzocco, Synesso or Slayer offer unrivaled power, bar pressure and accuracy, with agonizingly slow pulls extracting a few drops of precious brew.

Not only this, but shots of espresso are no longer a torrefied muddle of flavors -- on the contrary, the palate experience is brisk, detailed and bright. Nik Krankl, a barista splitting his time between Gelato Bar cafés in Studio City and Los Feliz, and the Coffee Commissary in West Hollywood, took second in the U.S. Barista Championship in Houston. He earned his trophy by teasing out completely different flavors from the same beans. Krankl can effortlessly pull a perfect shot of Brazilian roast espresso that will deliver aromatics of lime and pomelo. But simply by altering the pressure and the length of the pull, he can deepen the flavors to the realm of chocolate-covered cherry -- same coffee, different result.

In the new cafe, more attention is being paid to the origin of the coffee served than ever before. Your average cafe owner masters the flavor profiles of the world's coffee regions the way a sommelier masters the wine appellations of France.

For decades, such particulars of place were routinely obliterated in the roaster. Consumers were led to believe that the dark roasting techniques championed by tastemakers such as Peet's and Starbucks were a sign of quality, while the coffee's nuances were roasted into oblivion. Likewise, there arose the notion of a roaster as "master" of the cafe, a stylist who imposed his will upon the bean no matter where it came from or what flavors it brought to bear on the brew itself.

But the new roaster endeavors to minimize his thumbprint. He's not opposed to blending but seeks to isolate the virtues and strengths of the raw material, the particular flavors and character of the place or the variety, even down to the particular farm. "The idea is to develop the flavor, then capture it," says A.J. Barish of Culver City's Conservatory for Coffee. Martin Diedrich agrees: "We don't want you to taste the roast; we want you to taste the coffee."

At Intelligentsia, bags of single-origin coffee reflect a kind of homage to place, as with the pound of African beans that reads "Ikirezi, Burundi: Ngogomo, Muyinga Province, Bourbon Varietal," and lists elevation, harvest dates, roast dates, even a brief flavor profile ("blood orange and passion-fruit, with a brown sugar finish"). You may not require this full of an explication, but the "where" is there for the asking.

And the "who." Roaster Angel Orozco founded his pair of Cafecitos Organico in Silver Lake primarily to give growers a voice and a stake in his enterprise. Orozco spent time in Central America as an agricultural researcher and was taken with the hardships of organic coffee farmers. "I wanted to try and create a market for some of the farmers I met."

If even some of this rubs off, says Intelligentsia's Kyle Glanville, growers will benefit. "A big reason why coffee sucks is that no one can charge what it actually costs," he says, "which is ludicrous, since it's one of the most complex beverages in the world."

Photography credit: Mariah Tauger, Bob Chamberlin and Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times; Photography mosaic by: Kathy M.Y. Pyon / Los Angeles Times

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.