I get one last Lent with my Mami. I’m using it to learn our family’s capirotada recipe

- Share via

Easter is this Sunday, which concludes my favorite food holiday: Lent.

Cuaresma for Mexicans is a time for reflection and penance — but it’s also 40 days of gluttony. Have fun with your fish fries, fellow Catholics: We Mexicans are gorging on tortitas de camarones, shrimp fritters served alongside grilled cactus and doused in a fiery chile de árbol salsa. On gorditas stuffed with refried beans and cotija, dolloped with crema. I especially loved my mom serving crispy potato tacos from a pan filled with bubbling manteca as if she were pulling dishes from the sink.

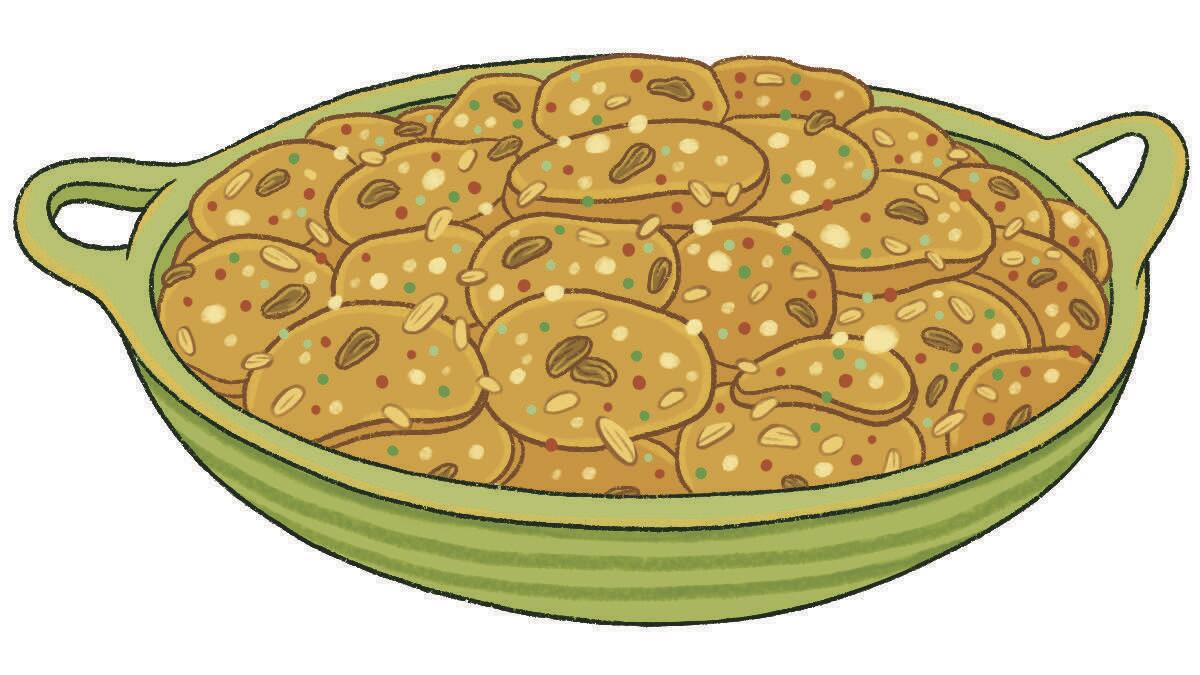

And the showstopper: capirotada, the layered bread pudding that’s the de facto Mexican dessert for Lent.

Every family bakes their own version; Mexicans on social media fight about whether it should include cheese (duh), nonpareils (of course), coconut flakes (maybe) or apple slices (no).

My mom’s is the best, of course. She uses queso añejo from her home state of Zacatecas for a salty touch, and sprinkles a judicious amount of raisins and almonds. The finished product doesn’t look elegant: bumpy and brown, and put into Tupperware once it’s cooled down. But her capirotada is sweet and earthy, crunchy (because of the fried bolillo slices she uses) and mushy (those bolillos get soaked in cinnamon-spiked syrup).

Cultura y amor in a baking pan.

The only thing I never liked about capirotada is its seasonality. From the time I was a kid, I’d beg Mami to make it throughout the year, a request she has always refused.

“Nomás se hace para Cuaresma,” she’d always scold — only for Lent, and that was that.

Once I became an adult, she took pity on me and prepped enough Lenten dishes to tide me over the year. I have enough goodies in the freezer to let me survive whatever comes after the Big One. And this spring, I dug through my freezer and found a small bag of capirotada, from a batch my mom made two years ago. I don’t think I’ll ever eat that one, though, because it’s from the last batch Mami ever made.

She is about to enter hospice, with weeks to live.

Maria de la Luz Arellano Miranda will pass away at 67, survived by her husband, Lorenzo, daughters Elsa and Alejandrina, sons Gustavo and Gabriel, and one grandson. Food, in complex and myriad ways, beyond the maternal glory of her cooking, defined her life.

Her grandfather, Sabas Fernandez, created Fervi, a dry, almond-scented chocolate de metate that makes the Ibarra brand taste like wallpaper. Her father, Jose Miranda (affectionately called “Papá Je” by his grandchildren), came to Anaheim in the 1920s to pick oranges and work at the Sunkist Packing House, nowadays a hipster food hall.

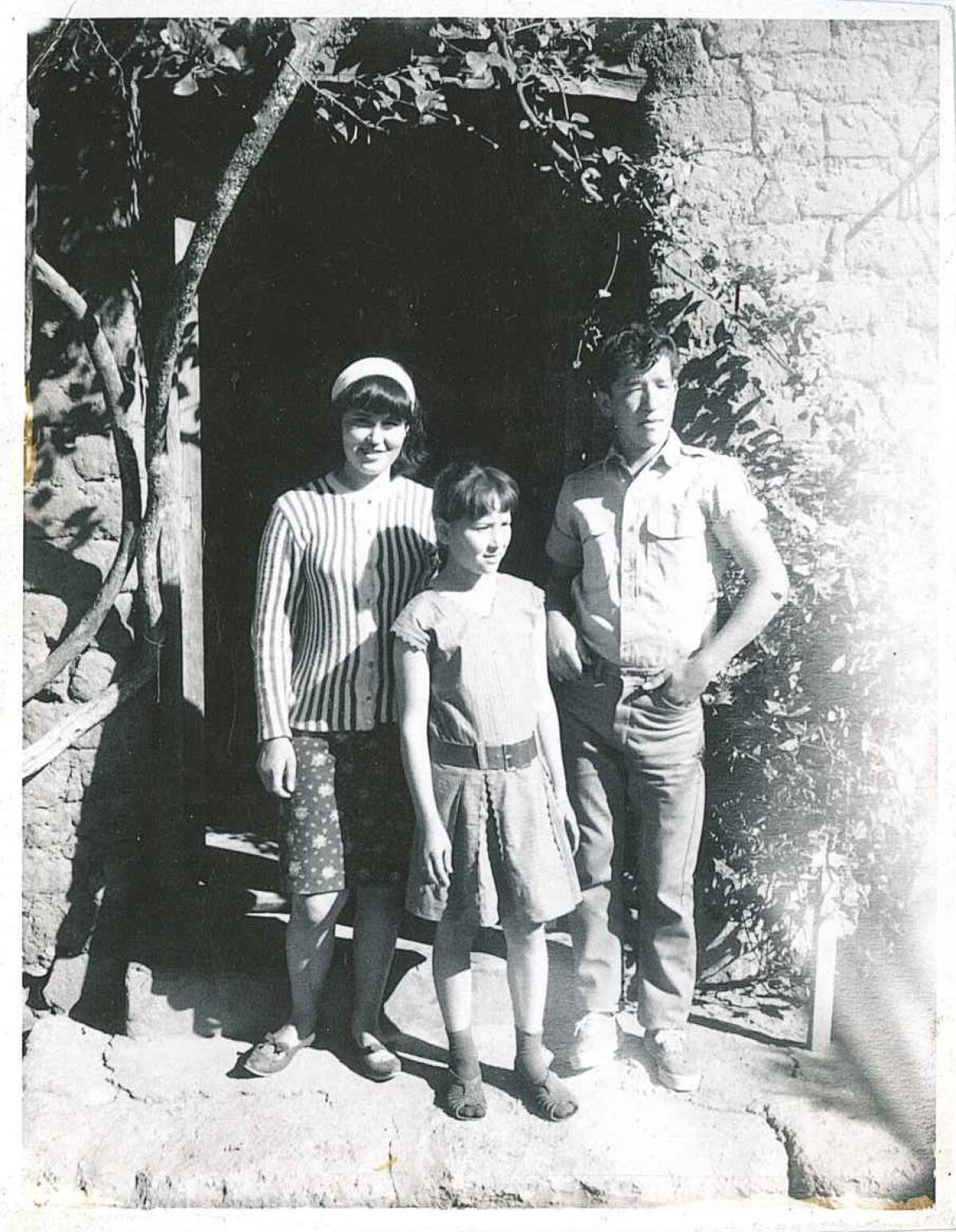

Mami grew up poor but well-fed in her home rancho of El Cargadero. My abuelito moved her and the rest of my aunts and uncles to the United States in the early 1960s because drought and frost had ruined Papá Je’s harvest. The Mirandas were part of a zacatecano exodus that has spilled throughout California for over a century. My family first went to Hollister, then Gilroy, where my preteen mom picked garlic and beets, before arriving in Anaheim in 1965.

She only made it to the ninth grade before my grandparents pulled her and my other aunts from school to help out la familia by working in the strawberry fields in Orange and Ventura counties. Those backbreaking days are the only time Mami ever admitted to drinking beer, because it offered her instant calories and temporary refreshment.

Deliverance came a few years later in the form of a job at the former Hunt-Wesson cannery in Fullerton. She first packed tomatoes, then learned how to drive a forklift, alternating between morning and graveyard shifts before the plant closed in 1997. It was a union job, so Mami got a living wage, benefits and free boxes of dented or mislabeled Hunt’s ketchup, puddings and Peter Pan peanut butter that helped her feed us kids.

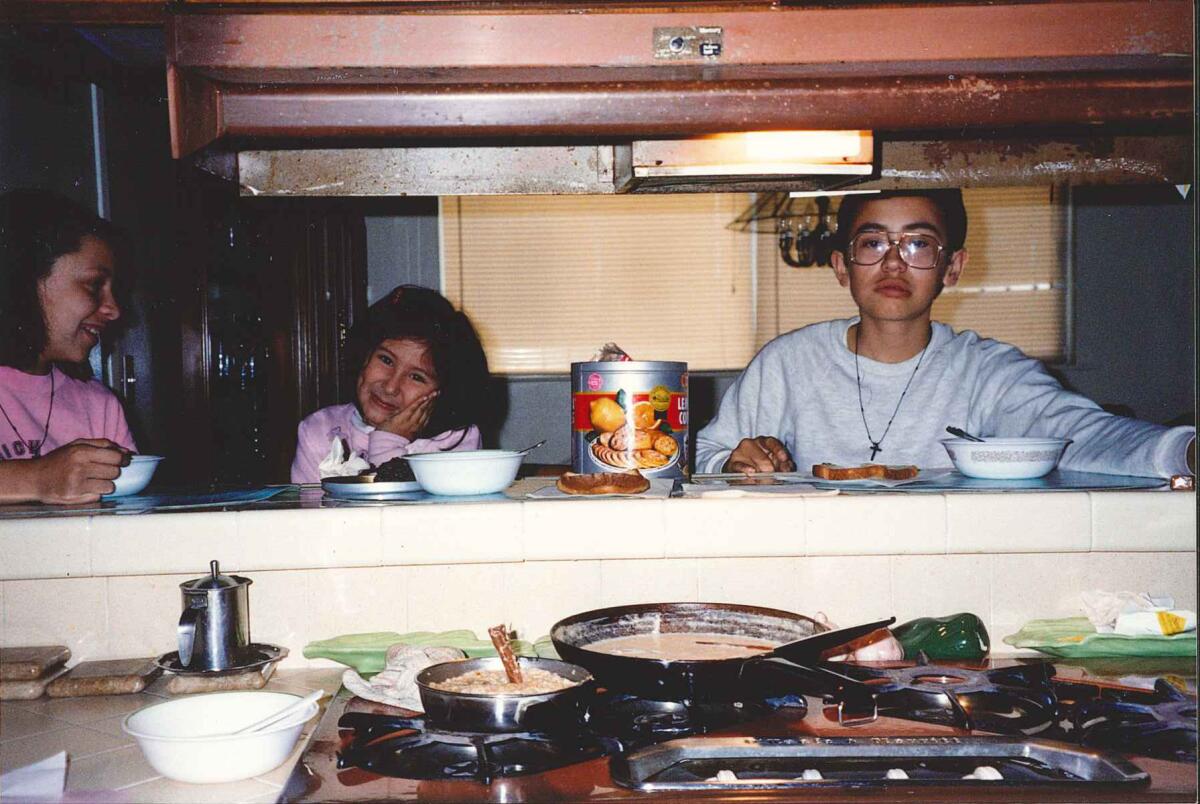

No matter how busy or tired she might’ve been, Mami always found time to cook breakfast and dinner for us nearly every day — and especially when we needed a feast.

I still remember my fourth-grade birthday party. We had just moved to a bigger home in Anaheim, and I invited a bunch of kids from my new school. Only one showed up. Mami saw how crushed I was, so instead of ordering Little Caesars, she pulled out a griddle and began to pat out gorditas for the two of us, entertaining us and making a show of it, a kind gesture my friend still remembers decades later.

In our extended family, she was respected for dabbing the right amount of masa in tamales, for a fabulous red pozole, and for her impossibly airy Christmas buñuelos (Mami’s secret: using spring roll wrappers instead of flour tortillas). Her enchiladas, chorizo tortas, and papas en crema con rajas spoiled us kids into believing all families ate like that all the time.

As the years passed, we began to realize that our mom was mortal and tried to mine her for recipes. She taught my sisters how to make tamales; my wife learned red pozole. In 2010, I persuaded Mami and her oldest sister, my Tia Maria, to share for this paper their recipe for asado de boda, the luxuriant mole of El Cargadero.

Our family still laughs about the morning the two made it. They argued over how much of each ingredient to use; I had to force measuring spoons and cups into their hands to try and cobble together a working recipe. They chastised me, insisting that cooking was better by tanteándole: learned by muscle memory through trial and error instead of measurements.

When I asked if maybe they could make a smaller serving portion than 32, Mami and my Tia Maria scoffed that Americans didn’t eat enough.

The Times went on to deem their asado de boda one of its 10 favorite recipes that year. But her capirotada is better.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Recipe: Jerez-style wedding asado (Asado de boda Jerezano) »

Mami was diagnosed with Stage 4 ovarian cancer in February 2018, just as Lent was about to start. She managed to make some chiles rellenos and arroz con leche before surgery — but not capirotada.

Chemo didn’t deter her from cooking, and Mami got better — but she still refused to make capirotada. Wasn’t the time. Finally, about a week before Ash Wednesday this year, she told my dad to buy bolillos from a local panaderia to air-dry before the first Friday of Lent.

My dad never got the chance. The following day, she went to the emergency room. She left the hospital two weeks later. Her digestive tract was shutting down.

I told her she’d soon get better, but Mami must’ve known her days were ending. She asked my Tía Maria to teach me how to make capirotada instead.

We got together on a Saturday morning, along with two of my aunt’s daughters. I came home to find a tray of bolillos Mami had put out to stale the day before, the day she told us that she was stopping chemo.

That would be her only hands-on contribution to the recipe — or so we thought, until, from her bed, Mami shouted out her thoughts on how much piloncillo to use in the syrup that gives capirotada its sponginess. Halfway through, Mami rose to check on our progress, harrumphed her approval, then returned to bed.

The capirotada turned out fabulous. Afterward, I sat next to her. She was falling asleep. Mami is now unable to eat solids and allowed only sips of water.

I wished I had written down all of her Lenten recipes over the years instead of trying to grasp at them before it was too late, I confessed.

“Just ask your cousins and aunts for them,” she said weakly.

“But they won’t be as good as yours.”

She stayed quiet for a while, then smiled.

“You’re right.”

When I’m at my most selfish, I curse God for striking my Mom with cancer during one Lent, then incapacitating her the following Cuaresma. He denied me two years of her cooking me my favorite meals — and once she passes, I’ll never have the chance to eat with her again.

It’s not fair, I cry during prayers. But then I remember what my sister Elsa taught me about capirotada years ago.

Many Mexican Catholics see symbolism in the dessert’s construction. The bread represents the body of Christ; the syrup, His blood; the cinnamon, the crucifix; the cloves are the nails (the two use the same word in Spanish, clavos). Every bite is supposed to remind us of sacrifice but also rebirth — hence, its Paschal timeliness.

I never gave much thought to that folk interpretation — but that’s all I think about now. Mami found everlasting life through the food she made us, through the memories created and the regrets I’ll always carry with me — but also the happiness.

I wish I jotted down more of Mami’s recipes. I wish I could see her beam one more time as I scarfed down her food even after a day of reviewing restaurants. Yet I’m forever grateful she found the strength to help me learn how to make her most hallowed treat one last time.

I’m no cook — quesadillas are about as fancy as I get. But now I will make capirotada for my family, so we can remember what a wonderful, giving woman our mom was.

And I’m only going to make capirotada during Lent — because that’s how Mami did it.

Zacatecas-Style Capirotada

(Mexican Bread Pudding)

1 1/2 hours. Serves 8 to 10.

Arellano’s family typically makes this recipe twice the size — “Why would anyone want to make a small serving of capirotada?” — but we scaled it down by half to make it fit perfectly in a more common 9-by-13-inch baking pan. If you want to make Arellano’s family-size version, look for an aluminum baking pan at your grocery store that measures roughly 16 1/2-by-10-by-4-inches (typically labeled “Extra-Large Rectangular Roaster Foil Pan,” “Ultra Roaster Foil Pan,” or “Full-Size Deep Steam Table Aluminum Foil Pan”). Buy bolillos in your grocery store’s bread case and let them dry out for at least 1 day or up to 1 week. “This isn’t a make-it-whenever dish,” Arellano says. “The drying is part of the ritual.”

12 ounces (1 1/2 cones) piloncillo

3 tomatillo husks

3 (5-to-6-inch long) sticks canela (Mexican cinnamon) or cinnamon sticks

2 whole cloves

1/8 small yellow onion

1/4 teaspoon kosher salt

2/3 cup rendered lard or vegetable oil

1 pound (6 to 8) stale, small bolillo or other white bread rolls, torn into 1 1/2 to 2-inch chunks

5 ounces queso añejo or panela, cut into 2-by-1/2-inch sticks

3 tablespoons whole almonds, toasted

3 tablespoons raisins

Freshly grated coconut flakes and multicolored nonpareils, to garnish

1 Heat the oven to 350 degrees.

2 In a small saucepan, combine the piloncillo, tomatillo husks, canela, cloves, onion wedge, salt, and 4 cups water. Bring to a boil and cook, stirring, for 5 minutes. Reduce the heat to maintain a gentle simmer and continue cooking until the syrup is reduced by one-quarter, about 15 minutes.

3 While the syrup simmers, heat one-third cup lard or oil in a large, straight-sided skillet or Dutch oven over medium-low heat. Once the oil begins to shimmer, add half the bread, stir to coat it evenly in the fat, then spread it out in a single layer and let cook, undisturbed, until lightly toasted on one side, 2 to 3 minutes. Flip the pieces and cook until toasted on the opposite side, 2 to 3 minutes more. Transfer the bread to a plate and wipe the skillet clean with more paper towels. Repeat with the remaining one-third cup lard and the remaining bread.

4 Spread one-third of the fried bread in the bottom of a 9-by-13-inch baking pan, followed by one-third of the queso, then sprinkle with 1 tablespoon each the almonds and raisins. Repeat layering two more times with the remaining bread, queso, almonds and raisins.

5 Pour the syrup through a fine strainer and discard the solids. Slowly drizzle the syrup evenly over the bread and cheese, then lightly press all the bread down to help them absorb as much of the syrup as possible. Cover the pan with a sheet of foil and bake for 30 minutes. Remove the foil and continue baking until the bread pudding is golden brown and crisp on top, 15 to 20 minutes more.

6 Remove the capirotada from the oven and let cool for 5 minutes. Sprinkle the top with coconut and nonpareils before serving.

Twitter: @GustavoArellano

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.