Our restaurant critic’s favorite cookbook in 2022 so far

- Share via

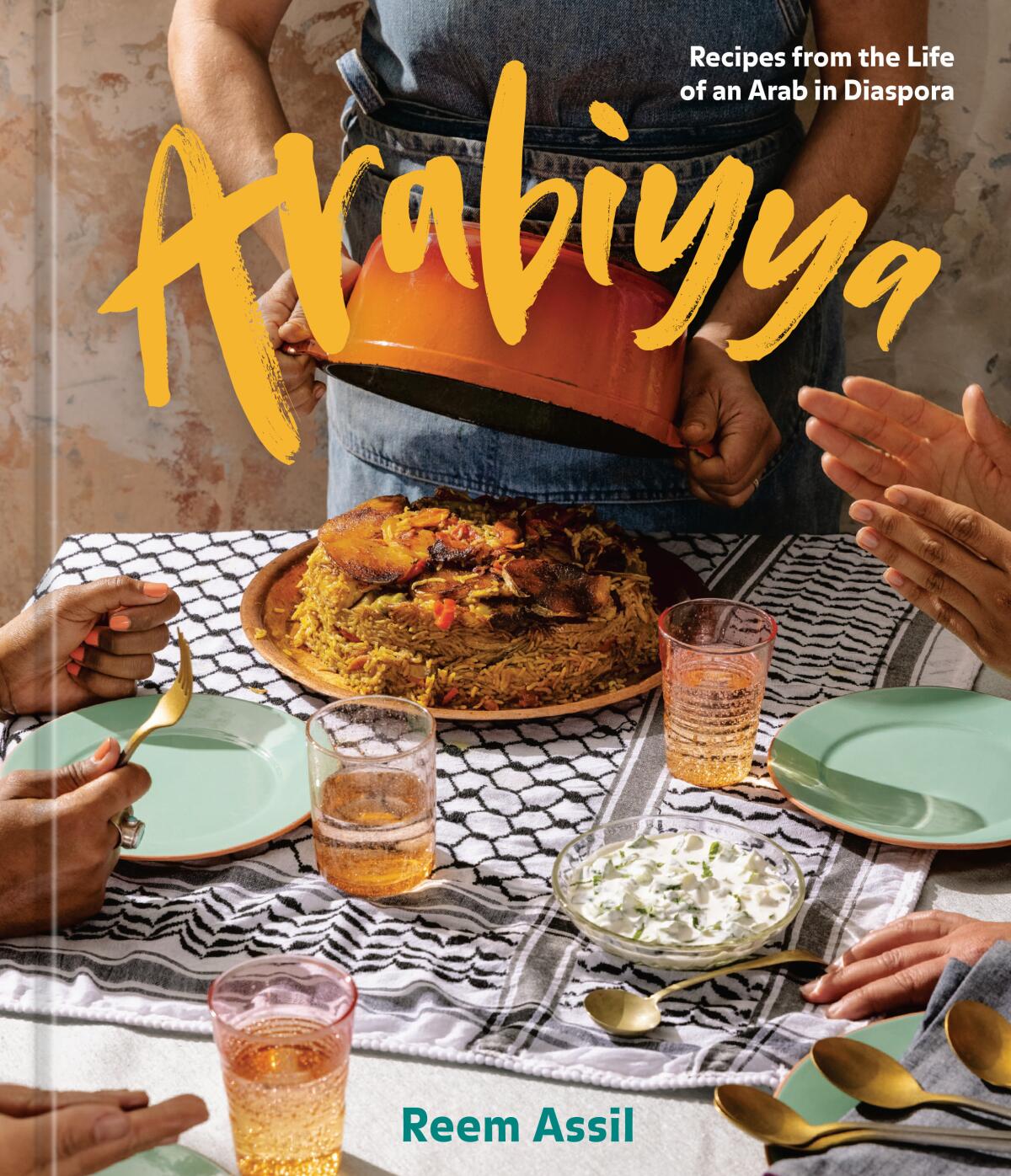

If you have been to Reem’s in San Francisco’s Mission District, a restaurant modeled on the traditions of Arab corner bakeries, you likely know the crackle and tang of the flatbreads, and how springtime strawberries find their way among the typical greens and fried pita in fattoush. There aren’t enough bakeries like Reem’s in the United States (proclaims this student of Arab foodways), but its existence has begun to inspire others around the country to similar heights of excellence.

And if you have ever heard of Reem Assil, the restaurant’s Palestinian Syrian chef and owner, you likely know she brings far more to her profession than superb baking skills. She was a labor and community organizer before switching to a culinary career, and she brings an activist’s soul to her life in the food industry. Beyond converting Reem’s to a worker-owned model in an effort to capsize hierarchical restaurant models, Assil has the courage to be outspoken on many topics: among them Palestinian rights, the intersection of food and social justice, and the many ills of capitalism.

She pours the breadth of her being into her first cookbook, “Arabiyya: Recipes From the Life of an Arab in Diaspora.” The secrets to her mana’eesh spread with za’atar and olive oil are here, as well as introductions to Yemeni honeycomb bread scented with orange blossom and rose waters, and tutorials on regional variations of savory turnovers. There is other beautiful food that channels her ancestry: djej mahshi (chicken stuffed with spiced rice) that’s ideal for Sunday dinner; clay pot shrimp scented with garlic and dried dill in the style of Gaza; and the ever-comforting kafta bil bandoura (meatballs in a heady tomato sauce).

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Of equal importance are the essays that frame each section of the book. She writes plainly and honestly of her family’s immigrant experience and the complexities of isolation, assimilation and ultimately resistance she’s processed to reach a sense of belonging in the world. Part One opens with memories of summertime family visits to Los Angeles but segues to her grandmother’s journey; she was one of the 700,000 Palestinians expelled from their home in 1948 during the creation of Israel.

So, yes, you can flip straight to the much-quoted passage on page 139 about her feelings on what fellow Palestinian author Leila Haddad calls the “hummus kumbaya” narrative. But any reader who has absorbed the context of the book in the preceding pages feels the weight of Assil’s intent: She is claiming the right to tell her own story.

Assil and I discussed this — and notions of seasonality in her cooking, and what her next book might be — in a conversation this week. One note: Many of my Arab friends these days express dissatisfaction with the term “Middle East,” a vague colonialist term that should go the way of “the Orient” in broadly describing Asia. Assil prefers SWANA — Southwestern Asia and North Africa — to position the area of her family’s origin, and it’s referenced below.

The Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

What is the reception of the book like for you, and how are you finding people’s grasp and understanding of food from this part of the world?

To write something so honest is pretty vulnerable. Part of the impetus for writing this book was to take back part of my own story; I felt like narratives get shaped around me, and it’s sort of polarizing. Like I’m either the controversial figure or the sweetheart, you know?

I wanted to just show the complexities and the nuances of what it means to be in diaspora, particularly as an Arab in this country and in this era. I set out to try to challenge stereotypes about myself, but then I had to remind myself to challenge stereotypes of other people in their understanding. In Texas, in Charleston and in other places where I didn’t know if people had access to Arab foodways other than, you know, the more whitewashed version of “Middle Eastern food,” people come up to me and know me and have told me how moved they are by the stories in my book. That’s been amazing for me. It’s like I’m coming out [laughs] and that people are accepting me and accepting the nuances of me.

As far as people’s understandings of our foodways: I’m pleasantly surprised by how familiar people are with some of the base recipes. Maybe that’s because of my restaurant. I come on this wave of Arab chefs who are claiming origin, and I feel proud of that.

In regard to recipes, your book reaches far beyond the savory and sweet baking and the other dishes you serve at Reem’s. It includes, say, homey shakriyah (spiced lamb and yogurt stew) and dinner party centerpieces such as the stuffed squid in arak-spiked tomato sauce. What was the recipe research process like for you?

The recipes follow the stories, as opposed to the other way around, as cookbooks are sometimes written. Even putting the pastries smack in the middle was a little controversial — but, like, this is the apex, right?

Some of the recipes were created for the book, and some I had collected over the years and tried to refine, and then some of them were our hits at Reem’s. The ones that I was trying to create for the book — I definitely had to dig deep into my memories. Hopefully I make this apparent in the book, but there is a kind of amnesia growing up in America as a child of immigrants. I didn’t have that romanticized experience of grand Arab meals. I really had to stretch to remember some of these things. I had to, like, sit down with my mom and ask, “What did we eat growing up?” And then, “Oh, that dish, yes. So how did you make it?”

Because with the generation before us, they didn’t measure anything. It was just a little bit of this and a little bit of that. My grandmother was the cook in the family, and she didn’t let anyone in the kitchen. Those recipes went away. She had dementia at the end of her life. Her caretaker would make the food, and she still thought she was the one cooking.

So it was hard to figure out, but then also in a way it didn’t matter — it was more the stories behind the dishes I wanted. I can develop the recipes. In the end, I think it was a nice meld between my interpretation as a California chef, without losing the soul of how my mom made it or my grandmother would make it.

The food of SWANA is so beautifully seasonal. Seeing what was growing in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley in the summertime a few years ago reminded me of Southern California. But so few of the menus in restaurants that serve food from the region express seasonality. Yours does, of course. I’m thinking of a manoushe with asparagus I had at Reem’s in March. But the book’s section on vegetables seems like a reclamation of sorts.

I had no idea at first that I would have a vegetarian section to the book. There’s a huge vegetarian population in the Arab world. Meat is expensive; it’s a commodity, it’s a luxury.

And of course, if you’re an immigrant in the States, you’re just trying to hold on to your culture, and you’re going to buy whatever you can find at the grocery store, so maybe that’s why you see a lack of seasonality. But I suppose “reclamation” is a good word for it. People will come up to me and say, “Oh, you put a California spin on this dish.” And I’ll say, “No, not really, there’s pumpkin in traditional Palestinian dishes too.”

What weren’t you able to fit into the book?

The merging of the Arab diaspora with other cultures is a subject I’ve been passionate about for a long time. The ethos of Reem’s is really to relate to the neighborhoods that we’re in — to find the convergence of ingredients and methodologies and explore them and celebrate them. My cooks are from so many different parts of the world, and their hands are on the food, you know? It’s what makes it even more delicious. They put that one little addition — you know, morita chiles on our labneh, or whatever. A couple recipes in the book touch on it, like the al pastor-style chicken, but there are a lot of restaurant specials we run that we also could have included in the book but didn’t.

But I’m really fascinated with Arabs in diaspora all around the world and how they’ve impacted the cuisine around them, but then also how those other cultures surrounding them have impacted their cuisine. And as I lay out in the first chapter [which opens describing visits to her grandparents’ home in Los Angeles], this first book is California — about California in the broadest spectrum, including the immigrant communities that move through it.

I wanted to tell these kinds of stories, but publishers came back and said, “Why don’t you tell your own story first?” And I was like, “Okaaay.”

Well, your work certainly creates space for diaspora connections on the most micro level. I think you might have a follow-up idea here.

Yeah, exploring the cooking of Arabs in diaspora just might be the next book.

Have a question?

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.