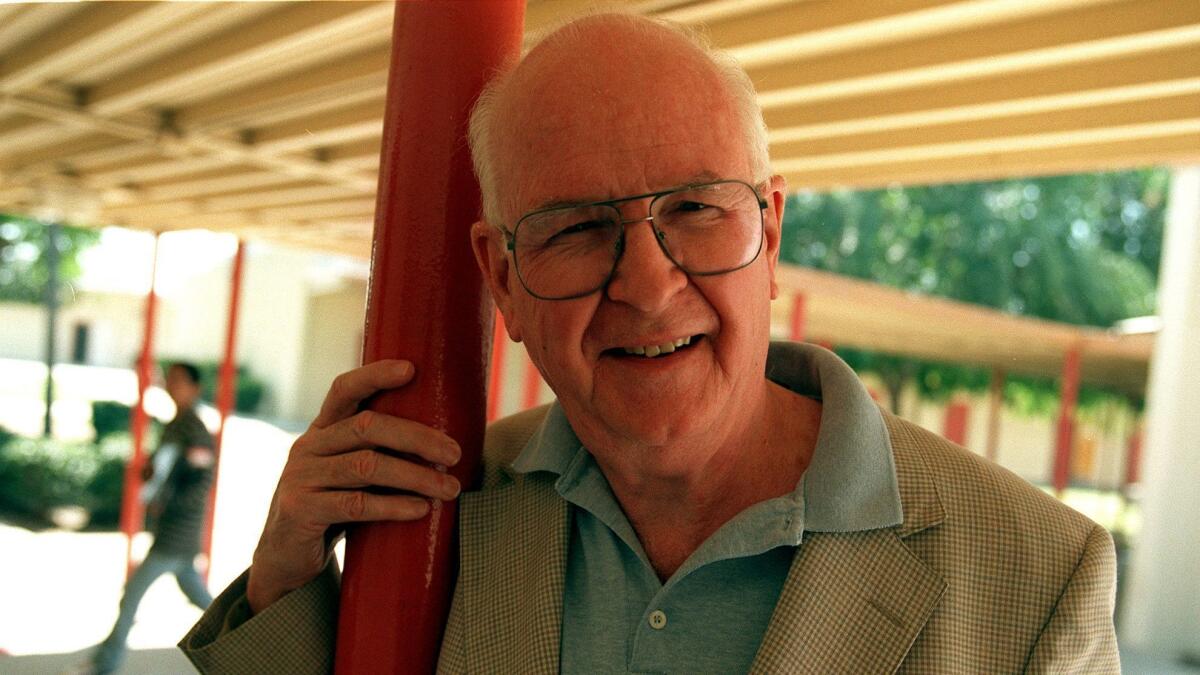

Glenn Langer, the cardiologist who helped disadvantaged students attend college, dies at 91

- Share via

When Glenn Langer retired as head of the UCLA’s cardiovascular research lab in 1997, he dipped into his retirement savings to buy books, calculators and tickets to museums and theaters.

Not for himself, but for disadvantaged students at Lennox Middle School.

Years earlier, during a visit to the school’s science fair, Langer had been impressed by the studious and motivated youngsters from the community east of Los Angeles International Airport. But he was saddened to know that less than 15% of the students from Lennox would go to college. So he decided to do something about it.

His philanthropy would help establish the Partnership Scholars Program, whose mission was to create academic opportunities for youth by providing “six years of educational and cultural experiences to academically motivated, but economically disadvantaged students, starting in the 7th grade, to promote college access and a lifetime of success,” reads its website.

Langer, who lived long enough to see his efforts shape the lives of hundreds of students, died June 19 in San Jose, said his wife, Renate Langer. He was 91.

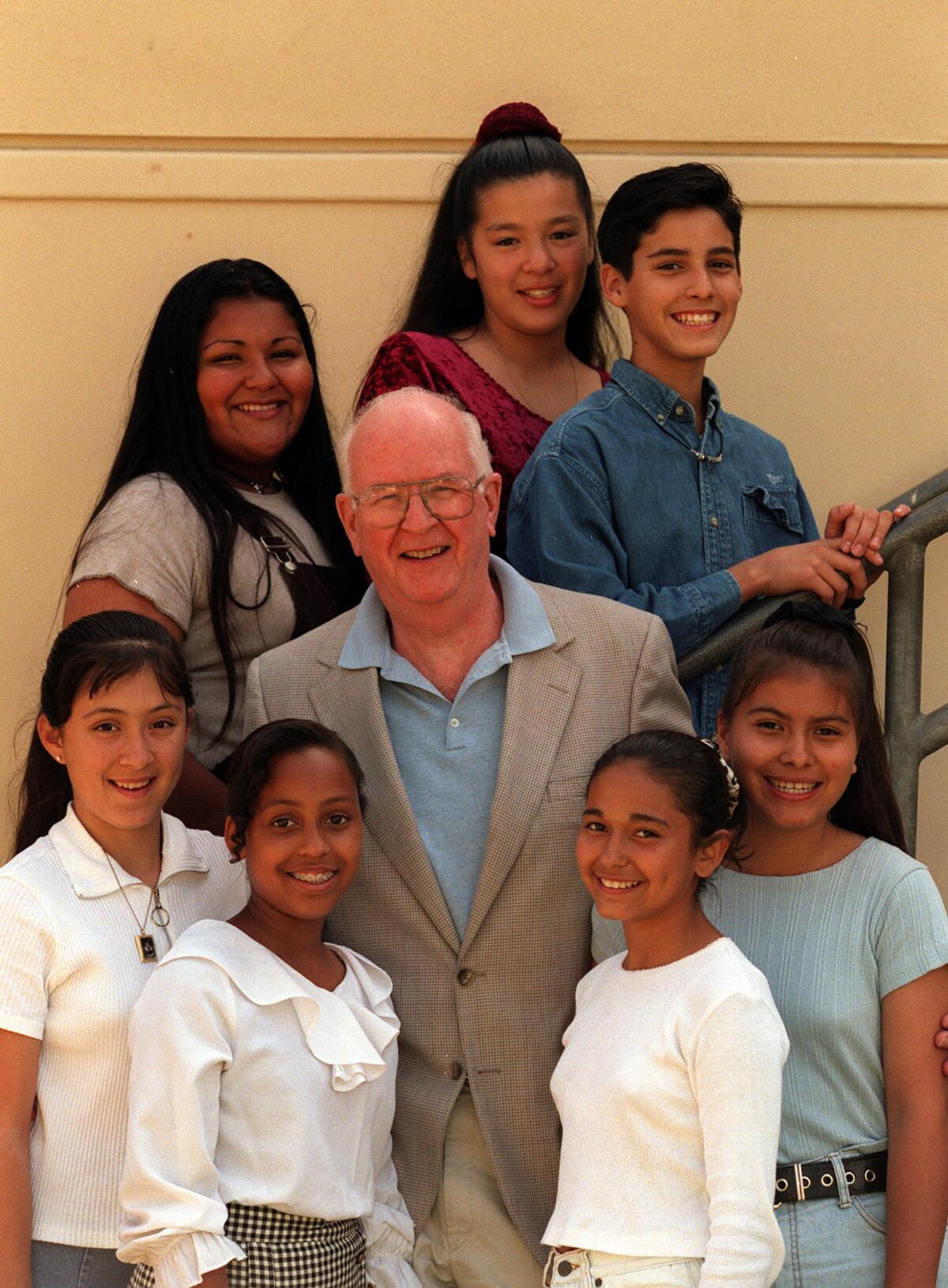

His first visit at Lennox Middle School would be the starting point of one of his greatest legacies. Impressed by the students, Langer decided to donate $8,600 to seven students over a six-year period to cover school supplies and pay mentors to work with each of them.

In following years, he sponsored another bunch of students, and by 1999, he had donated $235,000 of his savings. By 2006, Langer had committed about $600,000 of his retirement income to the effort. Now, every student receives a scholarship of $10,400 for the program’s six-year duration.

The program eventually expanded from Lennox Middle School to several other campuses in Los Angeles and Mendocino counties. Since it began, 622 students have been awarded scholarships, said Lisa Ruben, CEO of the program, and nearly 100% have gone on to college.

Walter Garcia was a seventh-grader at San Fernando Middle School when he was selected.

“Because of the program, I was able to have exposure to things I otherwise wouldn’t have been exposed to,” said Garcia, who graduated from the program in 2010.

His most memorable experiences included going to Dodgers and Lakers games, eating Indian food and traveling to Europe. Those experiences, he said, pushed him out of his comfort zone.

“By the time I graduated from high school, it wasn’t a far-fetched idea to apply to Brown [University],” he said.

He was the first in his family to earn a college degree, which opened job opportunities in Washington, D.C. Garcia, who served as Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra’s press secretary, now is a student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law in Chicago.

Now 27, Garcia often thinks about how lucky he was to have had the opportunities he did. Langer, he said, “didn’t have to help people like me or go out of his way to help others break out of the cycle of poverty, but he did.”

Langer was born in Nyack, N.Y., in 1928 during the Great Depression and grew up in nearby Pearl River. When he was 8, his father lost his job and was out of work for more than three years.

“We didn’t have a dime,” he told The Times in 1997. “If I hadn’t been helped by a private family foundation, who knows where I’d be today.”

That kindness and chance to continue his education helped launch a long and successful medical career.

Langer pursued an undergraduate degree from Colgate University in New York and earned his medical license from what then was Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1954. He went on to serve two years in the Army in Texas, his wife said.

He joined the American Heart Assn. Cardiovascular Research Laboratories at UCLA’s medical school in 1960. Beyond being a notable professor of medicine and physiology, he was director of the cardiovascular research laboratories, vice chair of the department of physiology and associate dean for research, among others.

Dr. James Weiss, UCLA’s chief of cardiology, once said that Langer “was an inspirational mentor and teacher whose self-described mantra was ‘I get paid for my hobby,’” he said. “Many of his trainees went on to become leaders in academic medicine and cardiovascular science.”

Dr. Kenneth Shine was one of them. Shine was UCLA’s medical school dean from 1986 to 1992 and later president of the National Academy of Medicine.

Langer was married to his first wife, Beverley Brawley, for more than 20 years before she died of a heart attack at 46. He later married Marianne, whom he founded the program with and was married to for about 35 years before she died in 2014. In 2015, he married Renate, a longtime friend. The two met in 1990 in Northern California while helping refugees from Sudan and Vietnam settle as they arrived in San Jose. They became friends, and years later, when both were widowed, they became a couple.

“[Langer] was a brilliant thinker who shared his mind with me all the time,” said Renate, a psychologist. “I learned every day from being his partner and wife.”

Langer loved nature and world literature and had a deep appreciation for music.

“And he adored dogs,” she added. “He always had a dog.”

In his lifetime, he wrote more than 200 scientific articles and co-wrote several books. For his work in the medical field, he received the Distinguished Achievement Award from the American Heart Assn. Science Council and the Distinguished Scientific Achievement Award from the L.A. County Heart Assn., among others.

He is survived by his wife, daughter, stepson, four grandchildren and three step-grandchildren.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.