Must Reads: The busboy who tried to help a wounded Robert F. Kennedy in 1968 dies. His life was haunted by the violence

- Share via

Juan Romero struggled for decades with a memory he could not escape.

He left Los Angeles and moved to Wyoming, later came back west and settled in San Jose, raised a family and devoted himself to construction work.

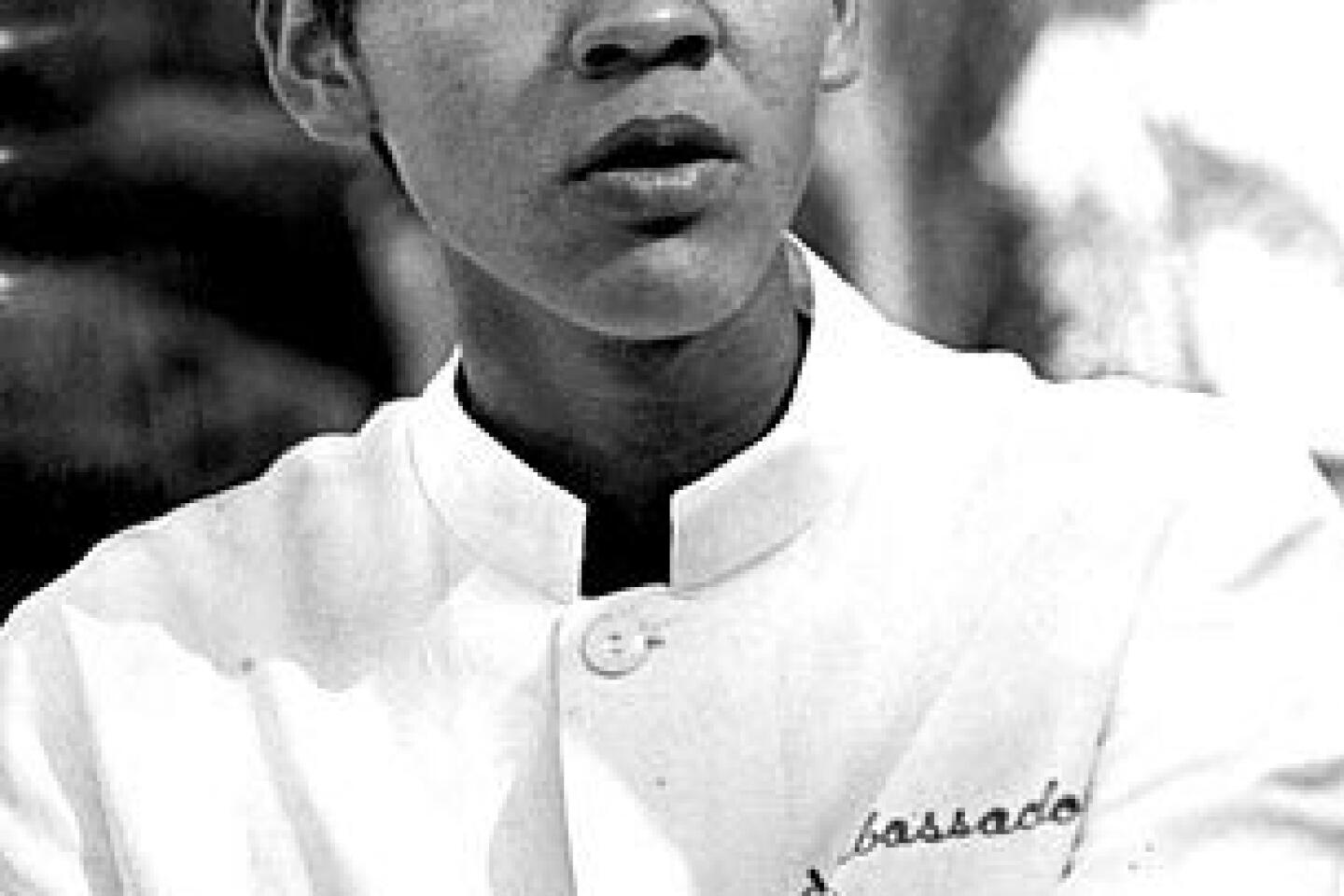

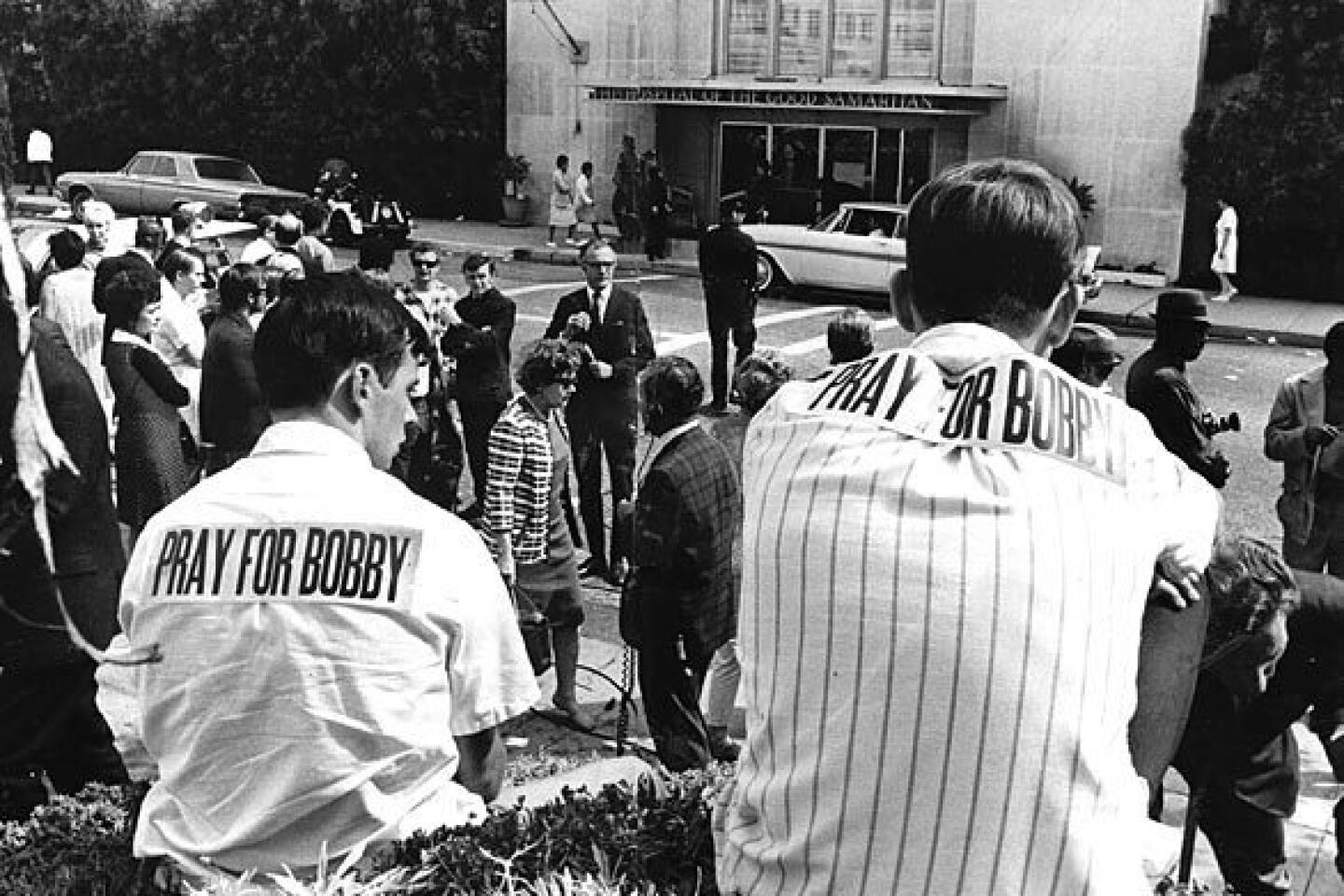

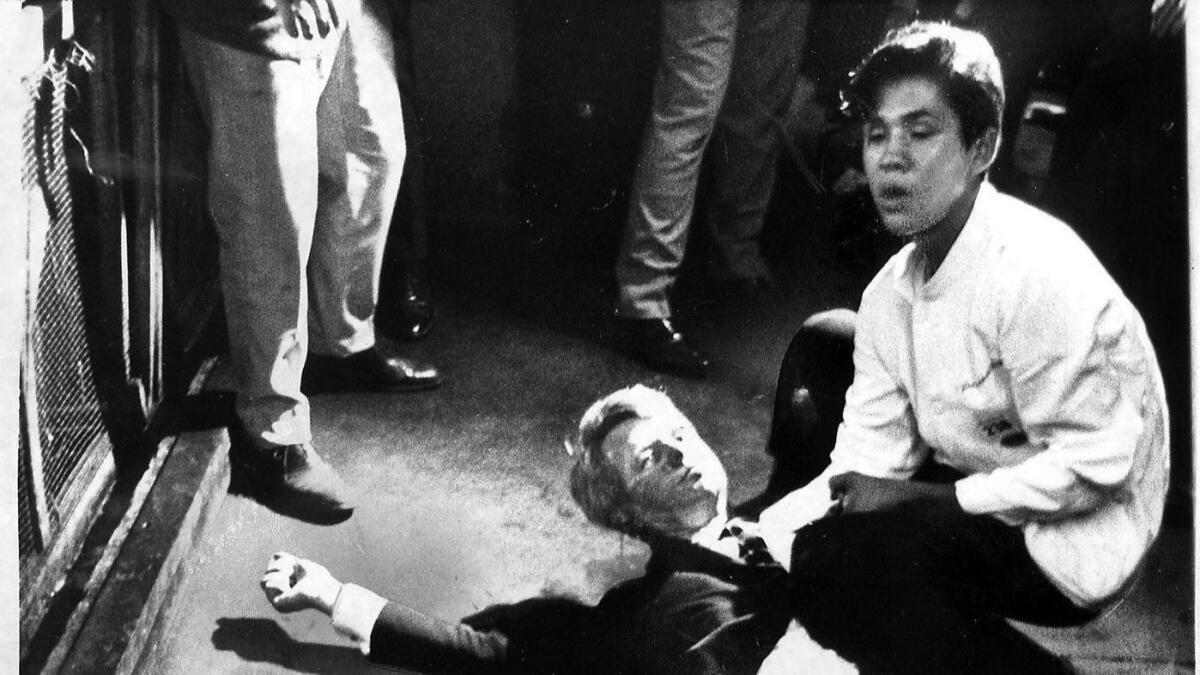

But still he was haunted by what happened just after midnight June 5, 1968, when he was on duty as a busboy at the Ambassador Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard near Koreatown. That was the night an assassin took aim at Robert F. Kennedy, a candidate for president of the United States. Romero, just 17 at the time, squatted next to the fallen U.S. senator, cradled Kennedy’s head, and tried to help him up before realizing how gravely wounded Kennedy was.

The photos of that moment, with confusion and despair in Romero’s young, dark eyes, made for searing portraits of 1960s upheaval and followed by two months the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and by five years the assassination of RFK’s brother, President John F. Kennedy.

It was only in recent years that Romero began to let go, and in my visits with him three years ago and again this past June, he seemed to have been revived. Finally, he said, he was able to mark his birthday after years of refusing to celebrate because it was in the same month as RFK’s assassination.

That only made the news of Romero’s death this week in Modesto, at age 68, seem all the more tragic.

“He had a heart attack several days ago and his brain went too long without oxygen,” said his longtime friend, TV newsman Rigo Chacon of San Jose. “He passed away on Monday morning.”

A niece and a brother confirmed Romero’s death, but family members were unavailable for comment.

Romero had not been ill, Chacon said. When I met with Romero in June, on the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s death, he told me he loved the hard, sweaty work of paving driveways and roads, and he had no intention of retiring. His marriage had failed many years earlier, but he said he was in regular contact with his children from that marriage, and he was giddy about a new romance with a Modesto woman.

That day, we met at a downtown San Jose park, near a monument to Kennedy. The candidate had spoken there not long before his death and told throngs of supporters that poverty and illiteracy were indecent, and he warned of “an erosion of a sense of national decency.”

Romero was in the habit of leaving flowers at that monument each year to mark RFK’s death. In our many conversations over the years, he said he often felt we were moving further politically from what he saw as a Kennedy legacy of tolerance and compassion.

When I met Romero in 1998, just before the 30th anniversary of the assassination, he fell apart in recalling the fateful night and how he happened to be in the hotel pantry area where Kennedy was shot. Romero told me he had met Kennedy the night before when the candidate ordered room service, and he felt honored by the way Kennedy shook his hand firmly and looked him in the eye with respect.

“I remember walking out of that room … feeling 10 feet tall, feeling like an American,” said Romero, who had moved to Los Angeles from Mexico seven years earlier. He became an Ambassador busboy on the advice of his strict stepfather, who worked at the hotel and wanted Romero to be sure to stay out of trouble on the streets of East Los Angeles.

The next night, after Kennedy won California’s Democratic primary and made a victory speech, he retreated through the kitchen pantry area and Romero pushed through the crowd to congratulate him. He said that just as he shook Kennedy’s hand, the shots were fired. Romero thought that the pops were from firecrackers and that Kennedy had fallen in fright, but Romero then saw blood spilling onto his own hand and realized what had happened as Sirhan Sirhan, the man with the gun, was apprehended. Romero said he was carrying rosary beads in his pocket and stuffed them into Kennedy’s hands.

MORE: The assassination of Robert Kennedy, as told 50 years later »

Romero was taken to the Rampart police station for questioning, then took a bus to Roosevelt High the next morning. He still had Kennedy’s blood on his hand and said he chose not to wash it off.

As if the experience wasn’t traumatic enough, Romero said he got letters from people congratulating him for what he did. That made him uncomfortable, and so did letters from people asking him why he didn’t do something to prevent the assassination. He got tired of being asked by Ambassador guests to pose for photographs, found work in Wyoming, then made his home in San Jose.

In 2010, I met up with Romero in Washington and went with him to Arlington National Cemetery, where RFK is buried. He said he wanted to pay his respects, tell Kennedy he had tried to live a life of tolerance and humility, and to apologize. His buddy Chacon and I told him he had nothing to apologize for, but Romero knelt at the grave, spoke softly and wept.

Five years later, Romero emailed me to say he was finally feeling better with the help of a friend he had met on Facebook. She told him that when she looked at the photos from the Ambassador, she saw a brave young man who tried to help someone who’d been hurt, even as others retreated.

I heard from former California First Lady Maria Shriver, a niece of Bobby Kennedy, after I wrote that column. She said she wanted an address to send a thank-you note to Romero.

“I always felt a great deal of empathy for him … because of how difficult it was for him to move past that,” Shriver told me Wednesday evening when I called her with the news of Romero’s death.

Shriver said she never met Romero but hoped he came to realize he did the humane thing in a tragic moment, and she hoped he had found peace in the end.

“God bless him,” Shriver said. “It’s kind of hard to know why someone gets put into a situation that they’re locked in forever. But as I see it, he was locked into an image of helping someone.”

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.