In a city already known for civic dysfunction, San Bernardino could now be known nationally for something worse

- Share via

The whine of police sirens is familiar on the streets of San Bernardino.

But even here — in a place battered by drug addiction and decades of economic decline, culminating in the city’s bankruptcy three years ago — the kind of crime that sent an army of law enforcement officers into the streets Wednesday still has the power to spread fear and grief.

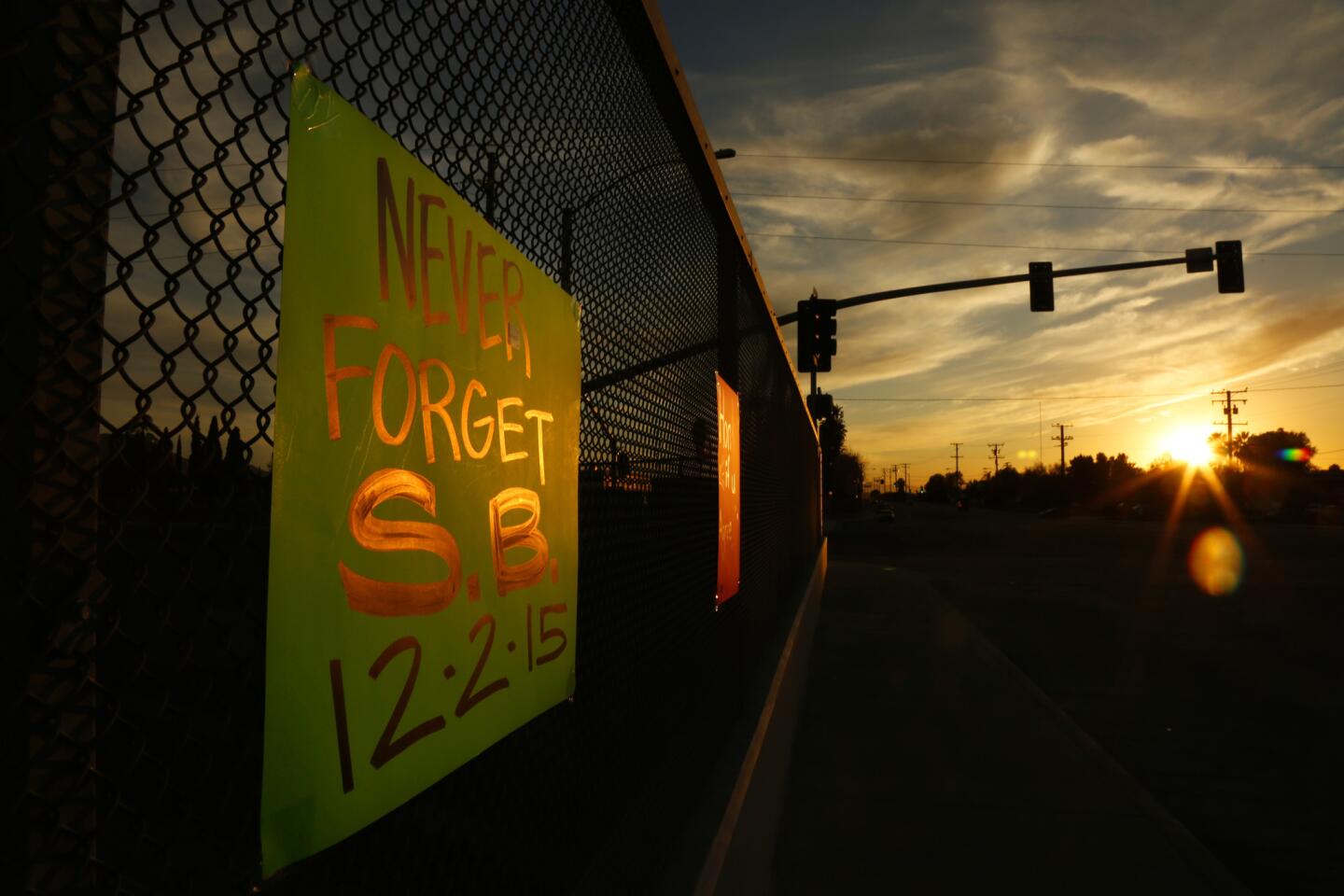

The shooting rampage that left 14 dead and at least 17 wounded at a social-services center would be a tragedy for any city. But it has special overtones in San Bernardino, which is among the nation’s poorest big cities and has arguably become California’s starkest example of urban blight.

Follow live coverage of the San Bernardino shooting >>

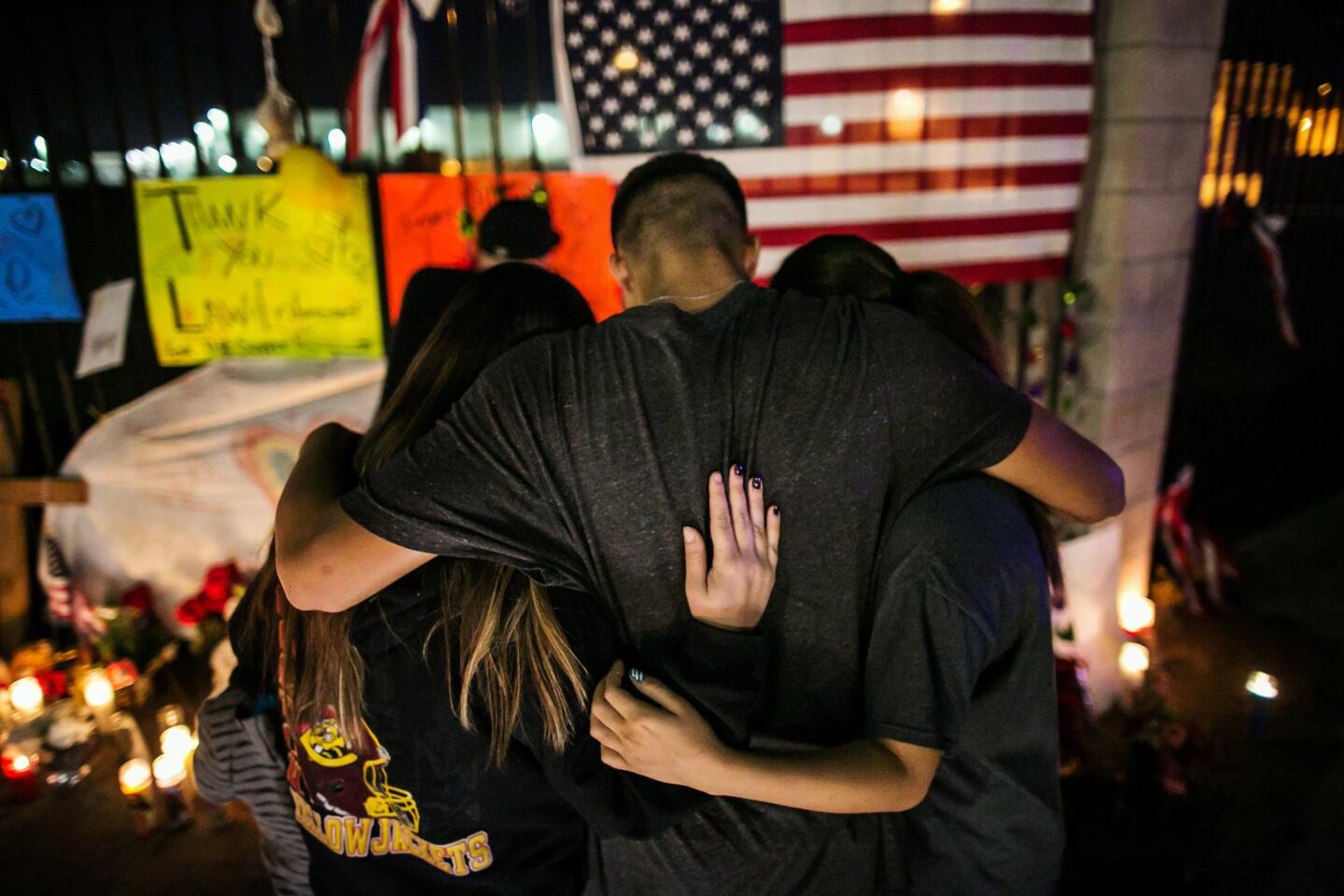

In the hours after the shooting, as schools and government buildings were locked down and armored police vehicles rolled through downtown, some San Bernardino residents were already expressing anger, sorrow and resignation at the knowledge that their city, for years synonymous with civic dysfunction, could now be known nationally for something worse.

“It’s shocking, because nothing like this ever happened in San Bernardino,” said Rosalinda Rosales, 28, whose 10-year-old daughter was sequestered Wednesday afternoon at Juanita Blakely Jones Elementary School. “I’ve heard a lot of shootings. But a shooting like this?”

Patrick Morris, who was the city’s mayor from 2006 to 2014, said he worried the shooting would “unfairly tarnish” the city’s image as it slowly climbs out of bankruptcy.

“It deeply, deeply troubles me that this happened in our city — in any city,” Morris said. “But it’s a real double-whammy for this to happen during our recovery.”

This city of 214,000 has long suffered from the steady grind of crime that often accompanies poverty, drug use and slashed city services. Methamphetamine use is widespread. The county assessor himself was arrested for possessing the drug in a 2009 raid.

Gang violence is common here and a biker shootout earlier this year drew national attention. But violence on this scale was unheard of.

The number killed Wednesday at the Inland Regional Center, a facility that caters to the disabled, is about a third of the 43 slayings committed in the city last year.

The center sits in a commercial zone that has attracted some of San Bernardino’s newer and more upscale development.

Michael Segura, a 23-year-old artist and community activist, said it would be unfortunate if San Bernardino, for all its real problems, was identified with the shocking gun violence that has erupted in recent years from Connecticut to Colorado.

“These mass shootings are happening everywhere. It’s a soullessness in the culture. We’re losing our humanity,” Segura said. “It just sucks this happened to happen in San Bernardino. It just puts more negative light on the city.”

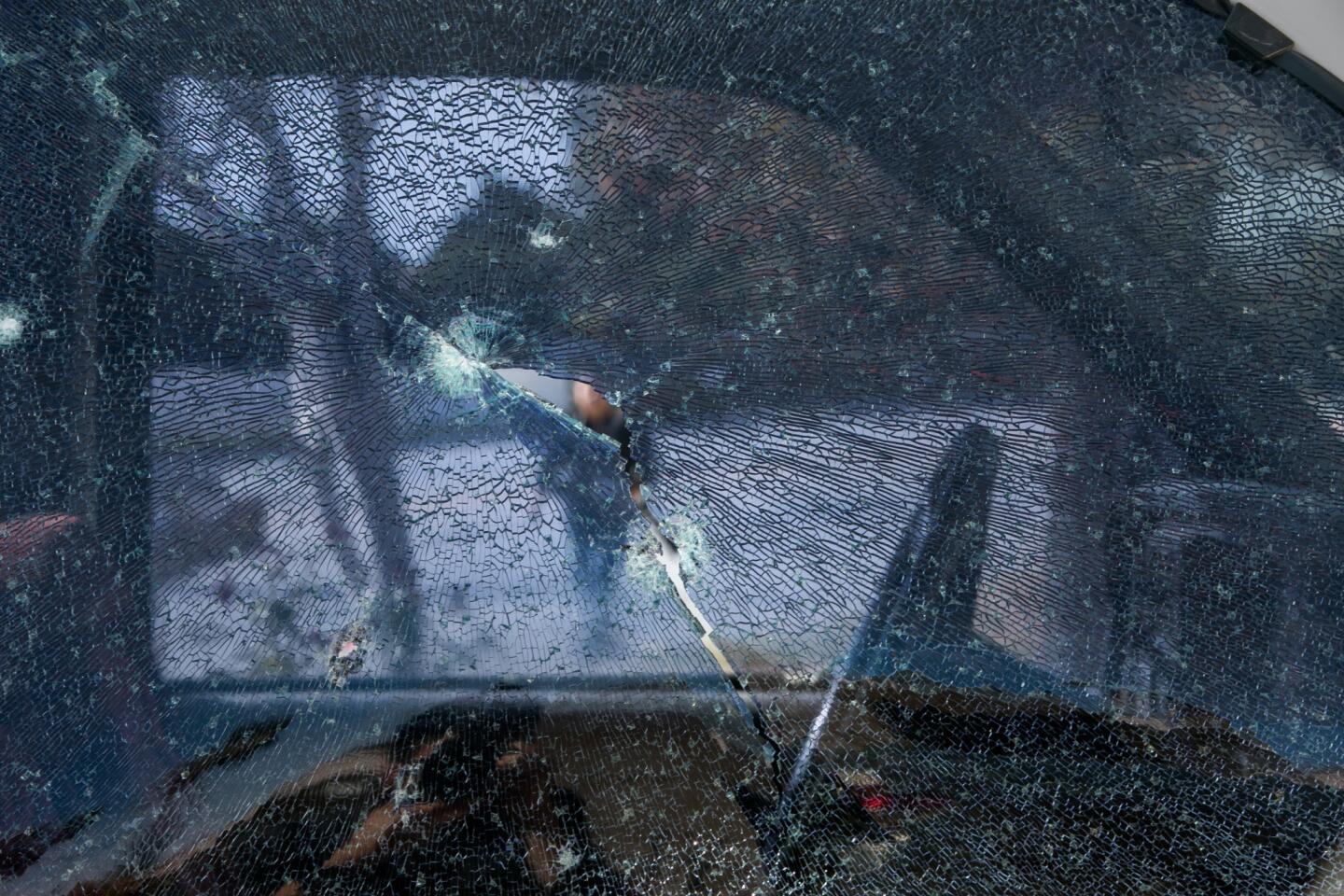

Much about the shooting was still unclear Wednesday night. Following a dramatic, televised car chase, police fatally shot a man and woman they said were connected to the shooting, but disclosed no information about their potential motives.

Meanwhile, San Bernardino appeared emptier and more desolate than usual, as public facilities were locked down and authorities advised residents to stay indoors.

Rosales and her mother, Theresa Crowell, found the downtown bank they had planned to visit closed and instead opted for a meatloaf dinner at Molly’s Cafe, a restaurant that sits alongside stores advertising loans, jewelry and check-cashing.

“It’s like a ghost town right now,” said Crowell, 58.

Some, like 57-year-old Diane Hayes, decided the safest place was home.

Hayes bought her clapboard house with periwinkle trim on 9th Street 14 years ago. After years of dragging their feet, she said, city officials tore down a crumbling building next door — only to look the other way as the now-vacant lot became a popular, and illegal, trash-dumping ground.

Hayes, unlike some others, said she didn’t think the mass shooting’s setting in San Bernardino was entirely coincidental.

“In this city, nothing surprises me anymore,” she said. “People know it’s a city in crisis. They’re going to do what they want to do, because we’ve had to cut back on police and fire and code enforcement.”

On Wednesday afternoon, Hayes was sitting inside her house with her granddaughter, Esmeralda, whom she had picked up from her locked-down middle school. The metal security door was closed and locked.

With the police busy chasing the shooters, Hayes said, there was no telling what could happen elsewhere in San Bernardino.

ALSO

How the massacre in San Bernardino set off a surreal day for hundreds

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.