Amid pain and division, California moves closer to tougher rules on deadly police force

- Share via

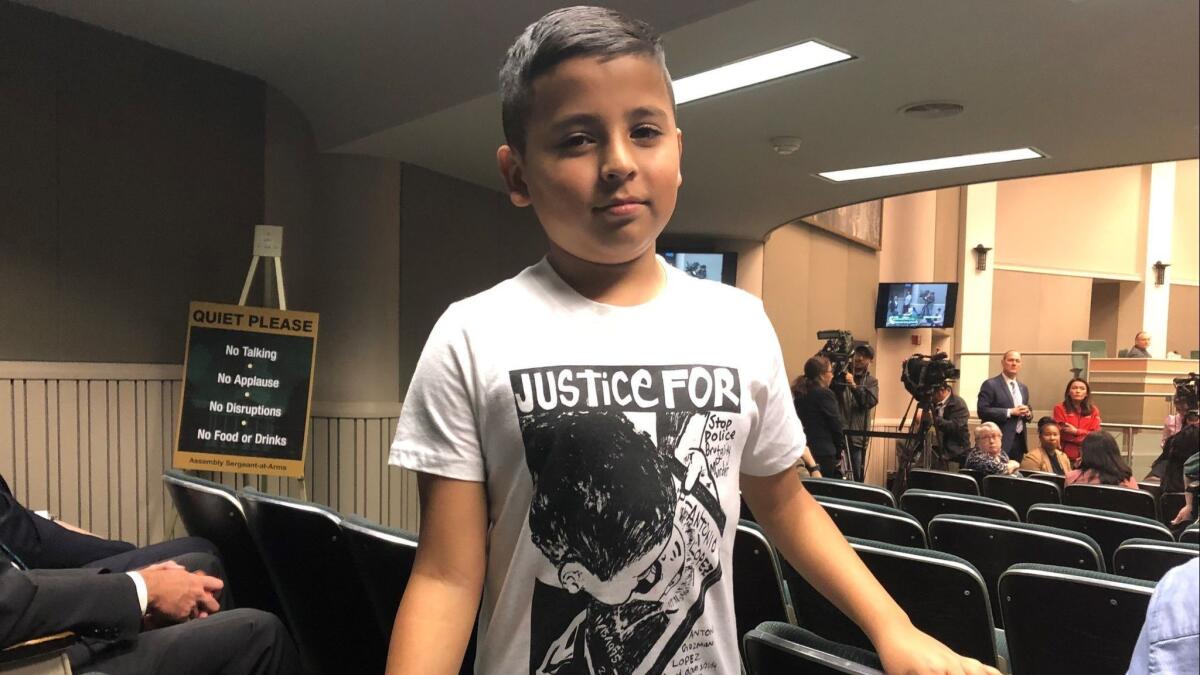

Reporting from SACRAMENTO — Josiah Guzman-Lopez, 9, missed school Tuesday to ask California legislators to support a proposal for new state rules on police use of force because “it just helps little kids’ lives,” he said.

His father was shot in the back by a San Jose State police officer five years ago.

Grief, frustration and mistrust filled a packed hearing room as speakers from law enforcement groups and reform activists — including dozens of family members of those killed by police — voiced their thoughts on Assembly Bill 392 as it faced its first move through the Legislature.

The bill passed its initial vote and will move forward to another committee. Yet hours of emotional testimony made public just how little common ground exists between law enforcement and communities of color, where black and Latino men have faced the brunt of deadly police violence. Both sides are passionate and have yet to find compromise — making the bill’s future uncertain.

“On both sides … we are all traumatized and that’s why it’s risen to this level,” said Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles), chair of the Assembly Committee on Public Safety, where the bill was debated.

Advocates for law enforcement spoke of their own pain when faced with violence, cautioning that they believed the bill would place them in danger by forcing them to hesitate in volatile moments.

Sacramento County Sheriff’s Deputy Julie Robertson described the unexpected shootout that killed her partner in 2018 when an armed felon, Anton Lemon Paris, opened fire as they entered an auto parts store in a Sacramento suburb while responding to a routine call. Paris allegedly shot Robertson’s partner, Mark Stasyuk, in the back of the head within moments of their arrival, then circled back to ambush Robertson.

“At one point, during the firefight, the gunman began shooting with only his back exposed to me,” Robertson said. “I recall in that moment thinking that if I were to shoot him in the back, I would be the next officer in the news, being scrutinized for my actions.”

Though the author of AB 392, Assemblywoman Shirley Weber (D-San Diego), was clear that such in-the-moment situations would not be affected by the bill, Robinson expressed the mistrust and acrimony that AB 392 has evoked for many rank-and-file officers across the state.

“This bill makes me wonder if sacrificing everything is worth it,” Robertson continued. “By the sounds of it, the only options given to me if handed a similar set of circumstances are to die, be criminally charged or live with the blood of innocent people on my hands.”

Robertson said the shooting is often on her mind.

“Feelings of helplessness, loneliness and despair constantly flood my thoughts,” she said.

Josiah and other relatives of people killed by police echoed those sentiments, highlighting shared trauma despite polarized positions.

“Deep down inside, [I] feel bad,” he said. “But if you let it all out, you feel better.”

AB 392, though billed as the toughest use-of-force standard in the country if passed, would not attempt to change the federal standard for when police are justified in using lethal force. Instead, it would bring into the state’s criminal code provisions already in place on the civil side, allowing an examination of officers’ tactics leading up to the use of deadly force. Currently, most use-of-force investigations are constrained to the seconds around the lethal moment.

By incorporating the idea that an officer could be criminally negligent in the lead-up to the use of lethal force, proponents of the bill say it will force district attorneys to expand their scope when investigating shootings, and thereby encourage departments to rethink their training and policies — creating greater accountability in the rare cases of unjustified shootings.

Law enforcement groups are proposing their own legislation, Senate Bill 230, which focuses on training and policy, including increased use of de-escalation. Police have been especially critical of a provision of AB 392 that would incorporate “reasonable” into the standard for when force is used, a bar that multiple speakers said would require “superhuman judgment” on the part of officers.

“There is one part of this bill I can never support. It’s not negotiable,” said Assemblyman Tom Lackey (R-Palmdale), a veteran of law enforcement. “And that is the term ‘reasonable.’ I want you to know that all public servants who swear a willingness to die in preserving peace are threatened by this very … term.”

When AB 392 passed out of committee, cheers erupted in a hallway packed by people in T-shirts reading #LetUsLive. Among them was Stevante Clark, brother of Stephon Clark, who was shot last year in Sacramento after police mistook his cellphone for a gun. AB 392 was crafted in part because of that shooting.

“It’s the first step out of the way,” Stevante Clark said later, standing on the back steps of the Capitol with the families of others who had lost loved ones to police shootings. “This is a club nobody wants to be a part of, but to see everybody come together and fight for something meaningful and lasting that will change the law, it’s powerful.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.