During the LAUSD teachers’ strike, Encino living rooms become classrooms

- Share via

Corey Moss, who normally runs a production company, stood at the head of his dining table, surrounded by 17 fidgeting third-, fourth- and fifth- graders.

He’d already had them work on language arts. They’d discussed how to identify musical beats. They’d studied math using football concepts — multiplying to tally scores and subtracting to figure out the yards needed for a first down.

They awaited his next lesson.

“We did football, we did DJ-ing,” Moss, 41, reminded them. “And now we’re doing …”

“Gambling!” shrieked his 9-year-old daughter, Lyla, from the table covered with poker chips and playing cards.

“Math,” Moss said quickly. “Tons of math in poker.”

All the children present were from Encino Charter Elementary School, which is run by the Los Angeles Unified School District. Their teachers are on strike, and they’ve stayed home in support. But they haven’t missed a day of learning since the strike began on Monday.

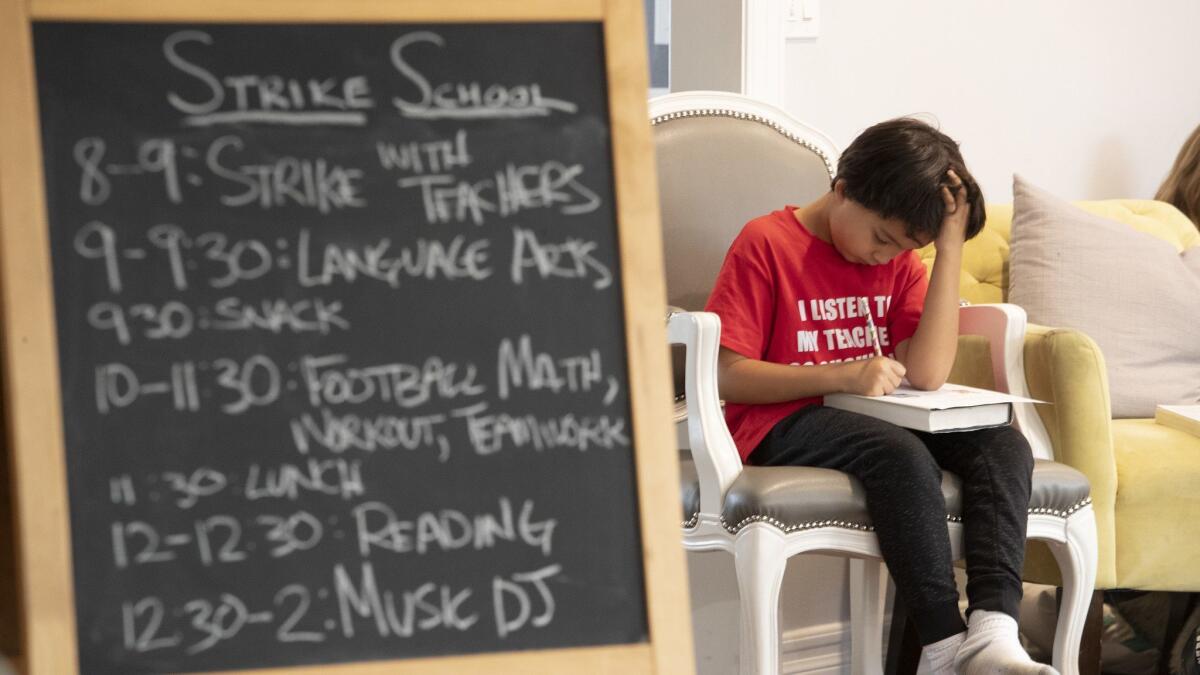

They’re attending “strike school” — full days of classes taught by 10 parents, who take turns being teacher and converting their homes into classrooms.

The Encino parents came up with the plan because they didn’t want to cross the picket line. But they also didn’t want their kids at home playing “Fortnite,” said parent Allyssa DelPiano.

Instead, the children have started each day outside their school, singing and chanting with their teachers, then headed to the living room of the day.

On Monday, Jacey Hayes, an attorney, dragged folding chairs and dining room chairs into her living room to form a circle around her L-shaped couch.

She sat on the couch, facing the group, and explained how class was going to work. “We’re going to be respectful of each other. We’re treating this like school … so take this seriously,” she told them.

She went over the rules: Bad behavior earns you a check mark. Three check marks, and your parents get called. Three verbal warnings and you’re sent home for the day.

Hayes then began her lesson, which was on labor relations. She discussed the rise of unions and the importance of collective bargaining, and described the perspectives of both L.A. Unified and the United Teachers Los Angeles guild. Then she read and led a discussion about a book: “Harvesting Hope: The Story of Cesar Chavez.”

In the course of the day, Hayes learned quite a bit about the challenges of teaching and got a taste of what was behind the educators’ call for smaller class sizes.

“I was so wiped out,” she said. So at the end of the day, she surrendered and put on the movie “Newsies.”

“The kids started talking about their class sizes and how they had more than double the class I had that day — and they do it without movies,” she said.

Hayes said she was surprised by the children’s inquisitiveness and school manners, even as they sat in lounging positions surrounded by friends, scattered in groups across the house — in bedrooms, at the dining table, on the living room carpet. Their hands shot up one after the other and they darted to find Hayes and ask questions about the material she’d created for them. She struggled to get to all of her students.

“I was just kind of running around like a chicken with my head cut off,” she said.

On Tuesday, DelPiano, a marketing consultant and artist, took her turn playing teacher. Her students summarized what they had learned the day before and then wrote letters to L.A. Unified Supt. Austin Beutner and their local representatives.

“I have to tell you I was amazed at how much the kids really understood,” she said of their knowledge of the strike. “It wasn’t like they were regurgitating a list. They actually talked about why.”

When DelPiano asked the students about one of the key union demands — to get full-time nurses, counselors and other support staff at school — one child said, “It’s not just for kids who have a problem! It’s for me, too. If I’m scared about taking a test, they can help me.”

“It blew me away,” DelPiano said. “I was, like, ‘Who are you?’”

Next on the agenda: Yoga, lunch and wildlife research.

DelPiano struggled to get through the agenda she’d planned, and she wondered how teachers managed it. She had planned an hour of free time before the kids got picked up, but there wasn’t any time left.

The kids researched animals and their oral presentations ran long.

“I don’t know how [teachers] do it with 30 to 35 students,” DelPiano said. “There’s no way.”

On Wednesday, a dad who works as a video editor had the kids make public service announcement videos on different topics, including bullying, the teachers’ strike and healthy eating. The students picked the subjects, wrote the scripts and acted out each scene before presenting it to their classmates.

Despite the fun, they seemed eager to go back to regular school.

“It was cool,” said Hayes’ 10-year-old daughter Emery. “But I think we should just be doing typical class. In school, you’re learning what you need to learn … so you can go to fifth grade. I feel like we’re falling behind.”

Lyla said she enjoyed making videos and being in her dad’s class, but she still missed her real one.

“I like this, but I feel like I like school because my teacher’s really nice and he’s also funny, so he makes class fun,” she said. “I kind of miss hanging out with my teacher.”

The latest on the LAUSD teachers’ strike »

alejandra.reyesvelarde@latimes.com

Twitter: @r_valejandra

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.