Facing a deadline, this South L.A. high school hustles to boost enrollment by 3 students

Door to door to boost enrollment by 3 students.

- Share via

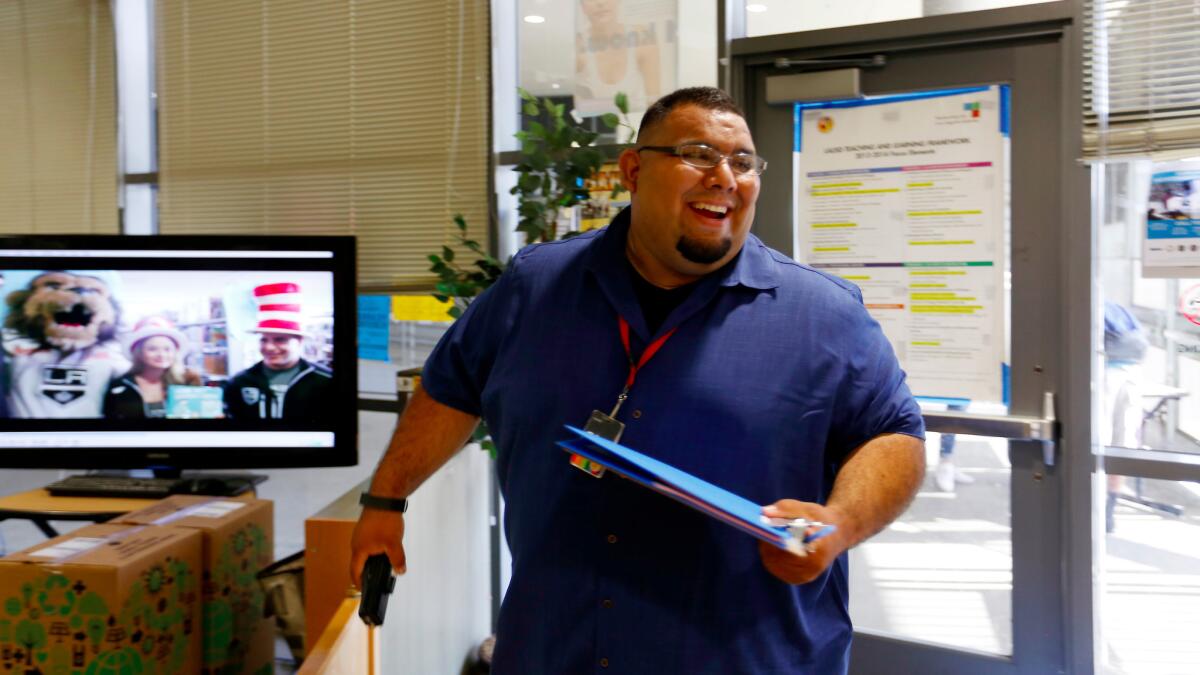

Four weeks into the new school year, Jose Lara, the dean of a South Los Angeles high school, approached a sagging white bungalow and shook the gate, summoning the household’s guard dog, a Chihuahua.

“Do you know where Stefani is?” he asked the woman who opened the door. She didn’t — in fact, no one knew where the 10th-grader was. The year before, Stefani had attended Lara’s school, the institutional-sounding Santee Education Complex. But over the summer she had disappeared with her 25-year-old Salvadoran boyfriend.

She was 16, her mother was dead, and her father was absent. The only people looking for her were an LAPD detective and Lara.

Lara climbed into his car, consulted his spreadsheet of missing students, and made a note by Stefani’s name.

“On my list of kids I’m going to visit today, one is incarcerated and one has been kidnapped,” he said dryly. “Let’s find out where the other ones are.”

On that day in September, Santee’s enrollment stood at 1,779 students in the general education program. (Students with special needs are counted separately.) Although this was a significant improvement over past years, it still was shy of principal Martin Gomez’s goal of 1,782, and time was running out. Like most L.A. district schools, Santee had until Sept. 16, “norm day” in education jargon, to increase its enrollment. For the district to pay for more teaching positions, all the school needed was three more students.

A one-time head count taken on Friday would decide which schools got more teachers and funding, according to a predetermined ratio, and which had to face the unpleasant reality of losing staff and redistributing children. Until then, a ritualistic scramble would take place, largely invisible to the public, but with real consequences.

It’s going to be very close.

— Martin Gomez

For a school opened in 2005 to relieve overcrowding, the fact that Santee was under capacity might seem like a sign of progress, but Gomez didn’t see it that way.

The school’s disastrous early years, marked by more than a dozen rival gangs fighting for control of the building — “open warfare,” as Lara put it — had taken a toll. As competition from charter schools and magnet programs grew increasingly fierce, Santee’s enrollment dropped, teachers were reassigned to other schools, and the campus became synonymous with chaos. Even the school’s original name, South L.A. Area High School No. 1, suggested no one wanted to embrace it.

Gomez, 39, and his predecessor had worked hard to make Santee safe and to improve its reputation and morale. Students became Falcon Scholars, named for the school mascot. Whereas Lara, 35, once kept extensive dossiers on every gang member, he hasn’t dug them out in years. Santee was becoming known as a school where teenagers from tough neighborhoods could take an array of Advanced Placement classes, play on the water polo team and join the school’s largest club, the Gay-Straight Alliance.

And while the Los Angeles Unified School District has been losing students — the district’s enrollment has fallen by about 200,000 students since 2003, due to declining birth rates and a charter school boom — Santee was defying the citywide trend. By 2014, its enrollment was ticking up.

The principal’s wish list included more security cameras and an outdoor LED sign that would flash news of the school’s triumphs. But those came second to his desire for two classrooms’ worth of laptops for every department, a need that grew out of the realization that some of his students answered California math exam questions incorrectly last year because they weren’t comfortable taking a test on a computer. The school’s test scores in math and English remained stubbornly low, a source of frustration for much of the staff.

All Gomez needed was three more students. But in South L.A., where competition for students has led him to set aside $50,000 annually for marketing and recruitment, meeting that goal by the district’s deadline would not be easy. Even if a hundred more students enrolled after that date, it wouldn’t make a significant difference. L.A. Unified’s head count was final.

Lara called this the district’s “fickle rule.”

“It’s going to be very close,” Gomez said.

Inside classrooms, his students were settling in, learning their schedules and teachers’ names. But in the surrounding neighborhoods, the hustle to increase enrollment was continuing. Gomez mobilized his staff, dispatching counselors, social workers and even teachers to dozens of students’ homes in hopes of finding truants and convincing them to give his school a second chance. To make the teachers’ participation possible, he hired five substitutes at a rate of $300 a day. The school’s list of no-shows had 114 students on it; if he could persuade just three of them to return, his investment would pay off, he reasoned.

Middle and high schools with truancy problems often try to track down no-show students. Typically, this effort is limited to one day, known as “recovery day,” which is ostensibly about finding dropouts, rousting them out of bed, and marching them back to school. And this does happen. Over the last eight years, the district says, it has re-enrolled nearly 4,900 teenagers. But at Santee the sense of urgency is particularly acute, and the recovery efforts especially aggressive.

It was because of this that Lara was crisscrossing South L.A. when he was scheduled to teach an ethnic studies class.

“Right now it’s urgent because we want to get our head count up and because it’s the beginning of the school year,” he said. He paused, then added, “but forget about the head counts, the numbers, the money, there’s a moral issue as well. And morally, we’ve got to do the right thing and get the kids into schools.”

More than anything, these house calls are a reminder of the incredible transience of L.A.’s students. Children change schools, neighborhoods and countries with such frequency that the contact information on the no-show lists often is out of date.

At one two-story house that had been divided into a seemingly infinite number of apartments, Lara was told the boy he was looking for had returned to Mexico when his mother was unable to find work in L.A. At another, a woman said her granddaughter had moved to Minnesota, following her mother, who was following a boyfriend.

“It’s a jewel when you find a kid at home,” Lara said. “It’s like, ‘Ah, this is one we can get back into school.’ ”

But as he neared the end of his list, the odds of such a success looked increasingly grim.

Asked for the whereabouts of his daughter Katherine, Walter Arevalo, 40, stopped sweeping his driveway and looked up, surprised. “She’s at school,” he told Lara. The teenager’s stepmother had enrolled her in a charter school that advertised smaller class sizes and more personal attention from teachers, but neither the girl’s parents nor the charter school had told Santee, where she was considered missing.

According to district officials, parents are supposed to formally withdraw their children when they transfer out, and charter schools are supposed to enter their students’ names into a state database, alerting district schools to the change. But over the several days that Santee staff made house calls and phone calls, they repeatedly encountered this sort of communication breakdown.

With a week remaining before the district’s deadline, Santee’s staff had managed to enroll five more students, one of whom was found sitting at home by himself, skipping school while his unknowing parents worked.

This should have been cause for celebration but was quickly tempered by news that a handful of students had transferred out of Santee. Further complicating matters, according to district rules, any student absent more than 13 days in a row could not be included in the head count. One boy had already missed 15 of 18 days of class.

Gomez had 1,780 students, and, with another week between him and the official count, he knew the unpredictable ebb and flow would continue. Santee could survive without its laptops and security cameras, but the principal felt it shouldn’t have to. He had raised the graduation rate every year of his tenure, reaching a school record — above the district average — of 83% last year. He and Lara had brought in a new program for gifted students. For the first time, four of the valedictorians from the area’s five middle schools had chosen to attend Santee. Why was it still such a fight?

“Need 3 more falcons by tomorrow afternoon!!” he texted on Sept. 15, with one day to go.

Assuming that his school’s enrollment would increase, Gomez had already hired five new teachers with money he had saved. If Santee hit his goal, he would be able to pay those teachers with district funding, freeing hundreds of thousands of dollars to be spent on other needs. But if he fell short, his laptop money would be consumed by the school’s payroll.

On the day of the count, shortly after the noon deadline passed, Gomez sent a text message to his staff.

It couldn’t be chalked up to dumb luck — the staff had worked too hard for that — but the events of the previous 24 hours were proof of how thoroughly public schools are at the mercy of forces outside their control.

The previous afternoon, a family that had just moved into the district walked into Santee’s main office and enrolled their three children in the high school. Then two more students transferred in, apparently unsatisfied with the local schools in which they had started the school year. The final tally: 1,784 students, two higher than Gomez’s goal.

“It was miraculous. It was what we were hoping for,” the principal said on Friday. “All of a sudden, they showed up.”

Twitter: @annamphillips

To read the article in Spanish, click here

ALSO

What happens to 116 high school students when their charter school closes a month into the year

High school student takes a stand by sitting for Pledge of Allegiance

UPDATES:

2:36 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.